From The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists:

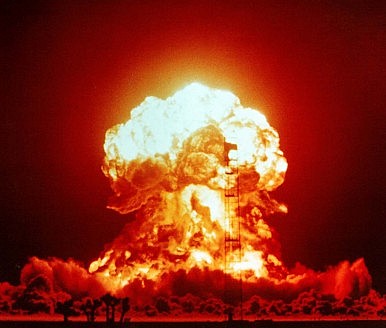

Why Russia calls a limited nuclear strike "de-escalation"

In 1999, at a time when renewed war in Chechnya seemed imminent, Moscow watched with great concern as NATO waged a high-precision military campaign in Yugoslavia. The conventional capabilities that the United States and its allies demonstrated seemed far beyond Russia’s own capacities. And because the issues underlying the Kosovo conflict seemed almost identical to those underlying the Chechen conflict, Moscow became deeply worried that the United States would interfere within its borders.HT: The diplomat, Sept. 6:

By the next year, Russia had issued a new military doctrine whose main innovation was the concept of “de-escalation”—the idea that, if Russia were faced with a large-scale conventional attack that exceeded its capacity for defense, it might respond with a limited nuclear strike. To date, Russia has never publically invoked the possibility of de-escalation in relation to any specific conflict. But Russia’s policy probably limited the West’s options for responding to the 2008 war in Georgia. And it is probably in the back of Western leaders’ minds today, dictating restraint as they formulate their responses to events in Ukraine.

Game-changer. Russia’s de-escalation policy represented a reemergence of nuclear weapons’ importance in defense strategy after a period when these weapons’ salience had decreased. When the Cold War ended, Russia and the United States suddenly had less reason to fear that the other side would launch a surprise, large-scale nuclear attack. Nuclear weapons therefore began to play primarily a political role in the two countries’ security relationship. They became status symbols, or insurance against unforeseen developments. They were an ultimate security guarantee, but were always in the background—something never needed.

Plus, time to ban hypersonic missiles? Some general interest links.