From The Economist:

Fund management: Will invest for food

Like books and music, the investment industry is being squeezed

SOME of the greatest fortunes in the modern world have been accrued by those who look after other people’s money. Hedge-fund and private-equity managers have become billionaires thanks to their ability to claim a chunk of their funds’ annual return. The irony is that many of these fortunes have been built at a time when investors no longer have to pay high fees to earn the market return for equities or government bonds. “Tracker”, or “passive”, funds do not try to beat the market. They just replicate the components of an asset class, and their fees amount to only a few “basis points”, as a hundredth of a percentage point is called in the lingo.

This distinguishes them from “active” funds where a manager tries to select assets that will do better than average. Such funds have higher costs and, unless they outperform markets over the long term (which the average fund does not), those costs eat into returns. Invest $100,000 for 30 years at 6%, with annual charges of 0.25%, and your portfolio will be worth almost $535,000; if the annual charges are 1.5%, your pot will grow to only $375,000.

Even great investors think that low-cost tracker funds make sense. In his latest letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders, Warren Buffett describes what should happen to his personal portfolio after his death. “My advice to the trustee could not be more simple: put 10% of the cash in short-term government bonds and 90% in a very low-cost S&P 500 index fund.”

As investors wake up to the maths, active fund management is starting to face the kind of pressure seen in other industries, like newspapers, record labels and taxi companies, which are losing their role as gatekeepers. A report by the accountants at PwC forecasts that low-cost funds will double their share of the global fund-management industry by 2020 from 11% to 22% (see chart 1).

Earlier generations of investors were prepared to believe that the returns achieved by fund managers were down to skill. Now it has become clear that the returns were the result of factors that can be replicated. Like shoppers on a budget, investors are trading down from expensive brands to white-label goods. That may put many active managers out of a job.

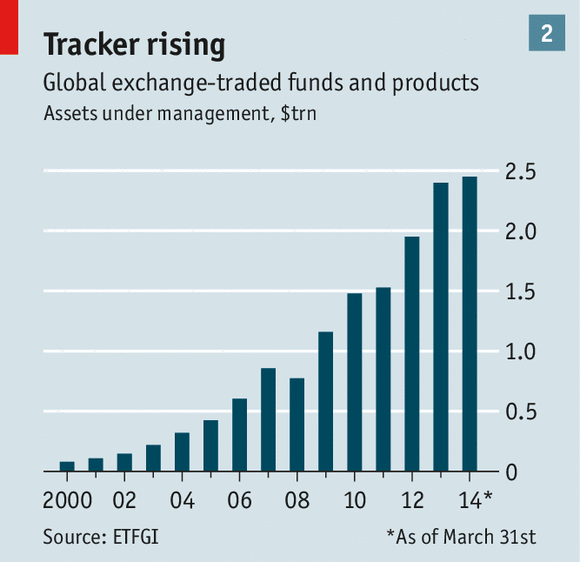

HT: AWM BlogThree factors are driving this commoditisation of fund management. The first is the rise of exchange-traded funds (ETFs)—portfolios of assets that track indices and trade on exchanges. Around $2.45 trillion is now invested in ETFs, up from just $425 billion in 2005, according to ETFGI, a consultancy (see chart 2). That makes this sector almost as big as the hedge-fund industry. The average fees on ETFs are just over 0.25%, but that proportion is inflated by specialist funds. State Street’s huge Spider fund, which tracks the S&P 500 index, charges only 0.09%.

The ETF sector is still small relative to the rival mutual-fund industry, which manages $27 trillion in assets, but it is beginning to close the gap. American ETFs received $895 billion of inflows between 2008 and 2013, compared with only $403 billion for actively managed mutual funds, according to the Investment Company Institute (ICI), an industry body.

One reason for the rise of ETFs is the changing behaviour of financial advisers. Historically, many earned commissions, paid by the fund-management company whose products they sold and incorporated in the annual management charge. This system created a conflict of interest: the products that were best for advisers to sell were not necessarily the best products for clients to own. Low-cost trackers did not have sufficient fees to reward the advisers, so tended not to be recommended.

The best way to insure advisers’ independence is for them to be paid by the client, not the fund. But few clients wanted to pay an upfront fee when the cost of commission-based advice appeared to be free (because it was subsumed within the cost of the product)....MUCH MORE