On a Sunday night in May 1935, Victor Lustig was strolling down Broadway on New York’s Upper West Side. At first, the Secret Service agents couldn’t be sure it was him. They’d been shadowing him for seven months, painstakingly trying to learn more about this mysterious and dapper man, but his newly grown mustache had thrown them off momentarily. As he turned up the velvet collar on his Chesterfield coat and quickened his pace, the agents swooped in.HT: The Browser

Surrounded, Lustig smiled and calmly handed over his suitcase. “Smooth,” was how one of the agents described him, noting a “livid scar” on his left cheekbone and “dark, burning eyes.” After chasing him for years, they’d gotten a close-up view of the man known as “the Count,” a nicknamed he’d earned for his suave and worldly demeanor. He had long sideburns, agents observed, and “perfectly manicured nails.” Under questioning he was serene and poised. Agents expected the suitcase to contain freshly printed bank notes from various Federal

Reserve series, or perhaps other tools of Lustig’s million-dollar counterfeiting trade. But all they found were expensive clothes.

At last, they pulled a wallet from his coat and found a key. They tried to get Lustig to say what it was for, but the Count shrugged and shook his head. The key led agents to the Times Square subway station, where it opened a dusty locker, and inside it agents found $51,000 in counterfeit bills and the plates from which they had been printed. It was the beginning of the end for the man described by the New York Times as an “E. Phillips Oppenheim character in the flesh,” a nod to the popular English novelist best known for The Great Impersonation.

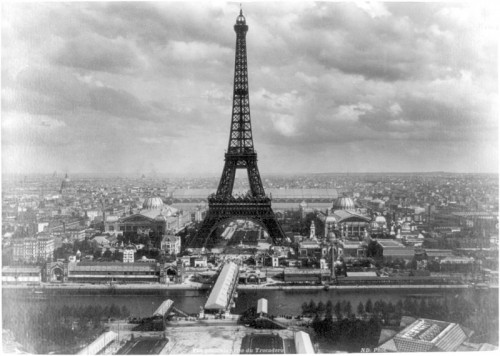

Secret Service agents finally had one of the world’s greatest imposters, wanted throughout Europe as well as in the United States. He’d amassed a fortune in schemes that were so grand and outlandish, few thought any of his victims could ever be so gullible. He’d sold the Eiffel Tower to a French scrap-metal dealer. He’d sold a “money box” to countless greedy victims who believed that Lustig’s contraption was capable of printing perfectly replicated $100 bills. (Police noted that some “smart” New York gamblers had paid $46,000 for one.) He had even duped some of the wealthiest and most dangerous mobsters—men like Al Capone, who never knew he’d been swindled....MORE

Monday, August 27, 2012

"The Smoothest Con Man That Ever Lived"

From Smithsonian Magazine: