That said he and Mr. Buffett are on different planets when it comes to talking about investments.

Did Warren Have Help in his Muni Call?

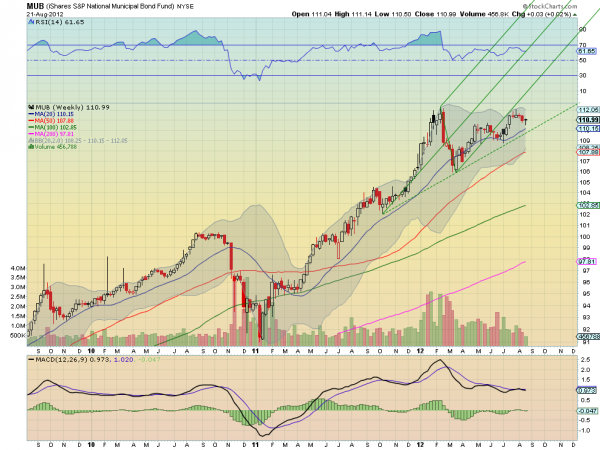

So I hear that Warren Buffett took another tubby and decided that Municipal Bonds were no longer a good thing to own. First questions: Was Meredith Whitney in the tub with him? Second: Dude what are you thinking? Giving him the benefit of the doubt and since he is a longer term investor let’s start with a look at the weekly chart to see what is out there.

The Andrew’s Pitchfork shows a break of the Lower Median Line followed by a retest and now a move back lower. Still over the Hagopian trigger line, which would indicate a bear move lower, but with the Relative Strength Index (RSI) bullish and Moving Average Convergence Divergence indicator (MACD) running flat, there is cause for caution but not a time to short yet. That foxy old man looks prudent on this time frame. But he has a very long view, maybe we should glance at the monthly chart as well. The rising channel dominates this chart. There are some signs of a topping action with the RSI flattening in technically overbought territory, with declining volume and a MACD that is fading. But the trend remains higher....MOREHere's how Warren talks, from the 2008 Letter to Shareholders:

...Early in the year, Berkshire offered to assume all of the insurance issued on tax-exempts that was on the books of the three largest monolines. These companies were all in life-threatening trouble (though they said otherwise.) We would have charged a 11⁄2% rate to take over the guarantees on about $822 billion of bonds. If our offer had been accepted, we would have been required to pay any losses suffered by investors who owned these bonds – a guarantee stretching for 40 years in some cases. Ours was not a frivolous proposal: For reasons we will come to later, it involved substantial risk for Berkshire.

The monolines summarily rejected our offer, in some cases appending an insult or two. In the end, though, the turndowns proved to be very good news for us, because it became apparent that I had severely underpriced our offer....

...Nevertheless, we remain very cautious about the business we write and regard it as far from a sure thing that this insurance will ultimately be profitable for us. The reason is simple, though I have never seen even a passing reference to it by any financial analyst, rating agency or monoline CEO.

The rationale behind very low premium rates for insuring tax-exempts has been that defaults have historically been few. But that record largely reflects the experience of entities that issued uninsured bonds. Insurance of tax-exempt bonds didn’t exist before 1971, and even after that most bonds remained uninsured.

A universe of tax-exempts fully covered by insurance would be certain to have a somewhat different loss experience from a group of uninsured, but otherwise similar bonds, the only question being how different.

To understand why, let’s go back to 1975 when New York City was on the edge of bankruptcy. At the time its bonds – virtually all uninsured – were heavily held by the city’s wealthier residents as well as by New York banks and other institutions. These local bondholders deeply desired to solve the city’s fiscal problems. So before long, concessions and cooperation from a host of involved constituencies produced a solution. Without one, it was apparent to all that New York’s citizens and businesses would have experienced widespread and severe financial losses from their bond holdings.

Now, imagine that all of the city’s bonds had instead been insured by Berkshire. Would similar belt tightening, tax increases, labor concessions, etc. have been forthcoming? Of course not. At a minimum, Berkshire would have been asked to “share” in the required sacrifices. And, considering our deep pockets, the required contribution would most certainly have been substantial.

Local governments are going to face far tougher fiscal problems in the future than they have to date. The pension liabilities I talked about in last year’s report will be a huge contributor to these woes. Many cities and states were surely horrified when they inspected the status of their funding at yearend 2008. The gap between assets and a realistic actuarial valuation of present liabilities is simply staggering.

Considering the apparent acceleration of muni bankruptcies in California, Vallejo in 2008 and in the last year Stockton, Mammoth Lakes and San Bernardino, combined with talk of "strategic bankruptcy" Berkshire saw the problem and acted, fast.

When faced with large revenue shortfalls, communities that have all of their bonds insured will be more prone to develop “solutions” less favorable to bondholders than those communities that have uninsured bonds held by local banks and residents. Losses in the tax-exempt arena, when they come, are also likely to be highly correlated among issuers. If a few communities stiff their creditors and get away with it, the chance that others will follow in their footsteps will grow. What mayor or city council is going to choose pain to local citizens in the form of major tax increases over pain to a far-away bond insurer?...

You can bet they won't be looking back at the decision.