Equity Valuation and Forecasting Future Returns and a Gift for our Readers

A subject near and dear to my heart. I may be the only person I've ever met who read every page of The Cowles Commission's Common Stock Indexes 1871-1937.From Cabinet Magazine:

[you must be a blast at parties -ed]

(links below)...

...That's Prof. Robert J. Schiller's Irrational Exuberance webpage. Here's his Yale homepage. When he took on Efficient Market Hypothesis back in the early '80's I decided I liked the guy. Publishing IE in March 2000 with the Nasdaq hitting 5048 (subsequent low 1114) pretty much convinced me. In addition to his professorships he's on the research staff of The Cowles Foundation for Research in Economics.

Mr. Cowles is quite explicit as to the reasons the Commission didn’t go further back than 1871. (pg. 4)

A big one is the paucity of publicly traded industrials.See also:

My favorite tidbit is the listing, among the pre-1871 industrials, of New York Guano.

Some things never change.

Here’s Yale’s (and my) gift:

http://cowles.econ.yale.edu/P/cm/m03/index.htm

It links to a big ‘ol hog of a PDF.

Does Stock-Market Data Really Go Back 200 Years?

Islands and the Law: An Interview with Christina Duffy Burnett

...Christina Duffy Burnett is a professor of law at Columbia University, where she teaches legal history, immigration, citizenship, and the US Constitution. Much of her work deals with the legal problems that arise at the margins of empire. She spoke with Sina Najafi by phone in June of 2010.

This is a very general question, but let’s take a stab at it anyway: do islands matter in the law?

The best way to get at this may be to start with something quite specific. In the summer of 2003, I stumbled on a 969-page typescript treatise which is kept in the library of the US State Department. Flipping through this great leather-bound brick of onion-skin pages, I gradually absorbed that the whole massive volume had been put together in the 1930s by a lawyer working for the US Government who’d been given a killer assignment. Apparently somebody had walked over to the desk of this poor functionary, scribbling away in some basement office, and said something along the lines of: “You know, we have a bunch of islands in the Pacific and the Caribbean—little islands. How about you figure out what the deal is with all these places, legally speaking.” I was holding the result: The Sovereignty of Islands Claimed Under the Guano Act and of the Northwest Hawaiian Islands, Midway, and Wake. And it was splendid to behold: nearly a thousand pages of intricate legal arguments and historical documentation on the strange history of the United States’ nearly invisible, but surprisingly vast, insular empire.

The Guano Act? What is guano? It’s bat excrement, right? Yes. And bird doo, too. In this case, it refers to the bird version.

So there was a US law about bird droppings that somehow proves important for thinking about the law of sovereignty? Indeed. The Guano Islands Act of 1856 arguably laid the legal groundwork for American imperialism.

Can you explain how? Basically what happened was that in the first half of the nineteenth century, Europeans and Latin Americans figure out that the phosphate-rich deposits of seabird droppings that had accumulated on many small Pacific islands make spectacular fertilizer. The stuff is like magic, and farmers everywhere are suddenly clamoring to get their hands on some. There’s a boom, the price skyrockets, the Peruvians more or less control the market, and supplies are short. Everybody is looking for new sources, there’s tons of fake guano trading hands—it’s chaos. Enter the US farm lobby. Farmers in the United States start pressuring Congress to pass some sort of legislation that will improve domestic access to this vital excrement. The result is the Guano Islands Act, legislation that authorized the United States to take control of a guano island if a citizen discovered it and undertook certain actions to take possession of it.See also:

What was new about that? Hadn’t Americans been taking possession of new lands more or less since the Mayflower?

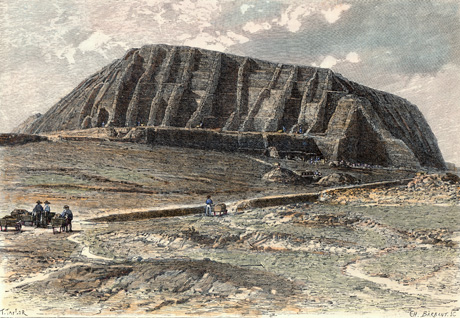

Hand-colored wood engraving from 1894 depicting guano being collected on one of Peru’s three Chincha islands in the mid-1870s. By this time, very little guano was left on the islands.

Right. In a way, yes. But in another way, not exactly. The history of US territorial expansion is actually very interesting, and not straightforward, legally speaking. As you know, initially there were those original thirteen colonies. But several of them also had “territories.” These were kind of their backlands to the west. When the newly independent states came together to form a union, and to write a constitution, they spent a certain amount of time trying to sort out how the territories were going to fit into the new nation. Hanging over all these negotiations was this broadly shared notion that the United States were destined to expand—indeed, that this emerging polity was likely, eventually, to extend across the continent....MORE

Peak Phosphorus: Scientists warn of lack of vital phosphorus as biofuels raise demand