The key concept, that post-journalism is written to confirm the reader's biases is almost a truism, for it can be no other way. The economics of the business will not allow a platform to constantly challenge and make uncomfortable the reader who pays the bills.

From Andrey Mir at Human-as-Media, December 30, 2025:

Postjournalism: The reversal of the media from news supply to news validation

“If the news is important, it will find me,” said Brian Stelter in 2008. People inevitably learn

the news that matters to them. Neither effort nor payment is required. When the scarcity of

content reverses to abundance, people no longer hunt for news—news hunts for people.

A chapter from The Digital Reversal. Thread-Saga of Media Evolution.

With the internet, news reliability might have degraded, but overall,

people became better informed. This flipped the value in content

production: news stopped being a commodity and became bait to attract

users for other purposes—mainly engagement.

It wasn’t a tragedy for the news media

yet, as they had always used news to attract audiences and sell them to

advertisers. The real issue was that advertisers moved to digital

platforms too, where they were provided with much better service than

the media could ever offer.

First, classifieds moved to digital,

taking a third of newspapers’ revenue with them. Corporate ads followed.

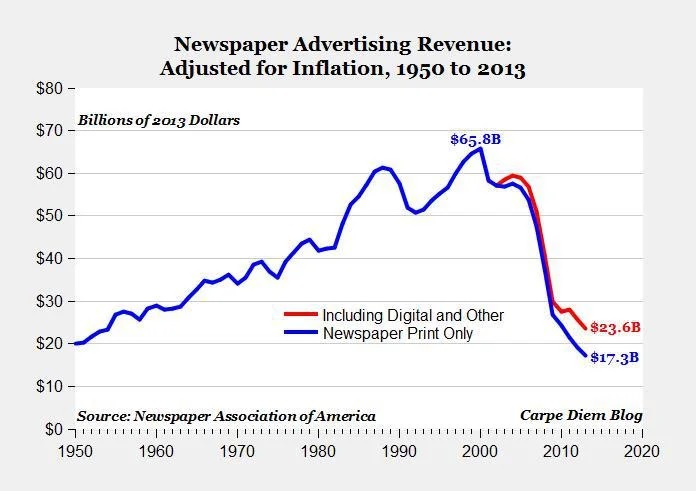

By 2014, ad revenue in newspapers had dropped below 1950 levels. The

entire economic foundation of the press vanished in just a decade.

The decline of ad revenue in newspapers.

Source: The Newspaper Association of America. [i] The collapse of advertising was a catastrophe. Throughout the 20th century,

the media were 70–80% funded by ads. Journalism was built on the

advertising model. When ad revenue dropped below what the media could

survive on, further reversals became inevitable.

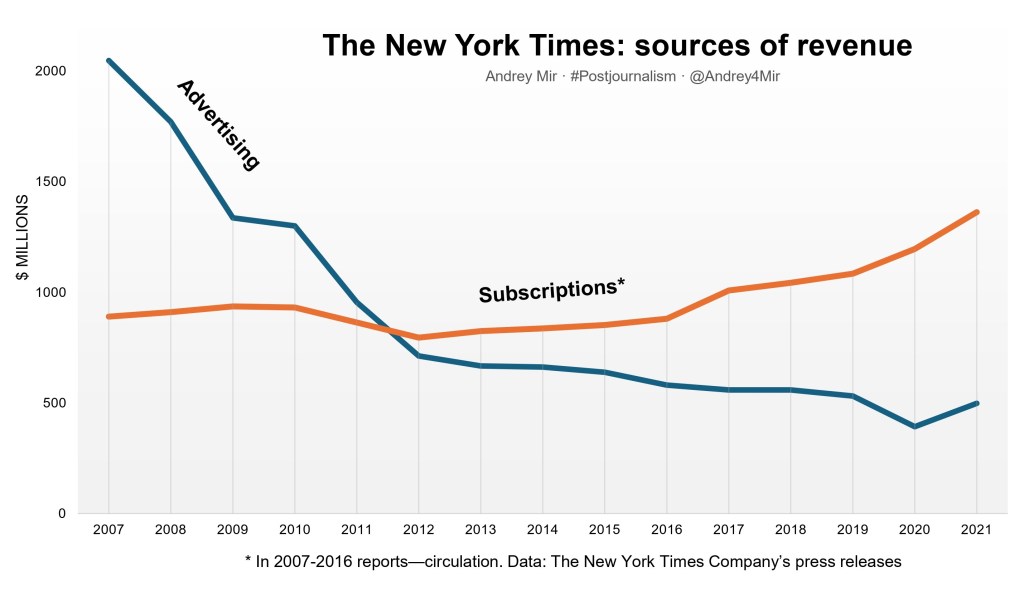

The first was the reversal of the business

model itself. In 2014-2015, newspapers’ ad revenue dropped below

circulation revenue. Not because subscriptions or copy sales grew—they

stalled or declined as well. But ad revenue declined faster.

(Experts know that later the New York

Times demonstrated subscription growth unmatched in the industry, but it

had little to do with subscriptions to news. Most of the growth came

from other products and packages.)

Similar dynamics hit TV and radio—ad money

was diverted to digital platforms. As a result, the business model of

news media flipped from predominantly relying on ads to relying more on

readers/viewers. The flip happened in the early 2010s everywhere.

***

Unrecognized by the public and the

industry, the business reversal changed newsrooms’ approaches and

mentality. After some awkward attempts to replace lost revenue with

auxiliary businesses, the media returned to their point of origin: the

readers.

As everything was moving online—it was the

period of the Digital Rush—the media tried to keep up. They started

chasing digital audiences, which at the time consisted mostly of the

educated, urban, young, and progressive. Most MSM targeted them as

potential digital subscribers.

This is where another unnoticed reversal

happened: instead of covering news for a broad audience, as they did

under the advertising model, news media started catering to a narrow

group of digital progressives. The reversal in business model led to an

ideological reversal.

Attempts to attract early digital

audiences radically changed news coverage, but no business came out of

it. Progressives were truly progressive—they didn’t consume news from

old media. Most paywalls, a popular trend in the industry in 2011–12,

failed.

The environment itself delivered the news. One didn’t even need to visit

media websites—news outlets posted their best headlines in our

newsfeeds. With friends’ comments selected by the

Viral Editor, it provided a fairly reliable picture of the day.

However, if something worrisome happened, people still needed someone

authoritative to confirm how bad it was. Old media suited the role of

bad-news notaries very well. They got the prompt and flipped news supply

into news validation....

....MUCH MORE

Previous visits with Mir:

Over the years we've linked to some of Mir's own writing with most links embedded in:

Andrey Mir: "How the Media Polarized Us"

...Having read a lot*

of Mr. Mir's words I think he is too facile in timing the polarization;

that he is shoehorning the facts into his mental matrix. To be clear,

this piece is far, far from as egregious an example as some of the books

that were popular a decade or two ago: "Business Lessons From Attilla

the Hun," where an author might have one decent insight but then tries

to stretch it out for two hundred pages, jamming as many square pegs

into round holes as necessary to get the needed word count.

Rather,

in Mr. Mir's case it's just that he doesn't put as much emphasis on the

fact that American media has always been partisan, and that in the

half-decade 1985 -1990 it went hyper-partisan.

However,

even if that observation is true (it may not be, who knows?), Mir knows

more about media ecology than just about anyone writing on the topic.

period.

*Previous links to Andrey Mir:

I'll get off this Andrey Mir, post-journalism kick, I promise. But not yet. (shades of St Augustine)

The

reason for my borderline obsession is the fact that mass media has

changed so dramatically over the last five or ten years, which makes it

imperative to understand and possibly channel the forces that attempt to

shape our everyday view of reality. And it really is getting close to

the point that the call to arms "If it isn't censored, it's a lie" is a

description of what is going on.

And that would be a shame, we like journalists and, among other reasons, get some of our best ideas from them.