From The Economist's 1843 vertical, July 24:

Thirty million Indians want a job on the railways, but a fiendish general-knowledge test stands in their way

You can listen to a podcast based on this piece on our weekly magazine show, The Weekend IntelligenceIn the summer of 2019, a 23-year-old student called Neeraj Kumar boarded a sleeper train from Delhi to the city of Patna in eastern India. A berth was beyond his means so he planned to sleep on the floor during the 16-hour journey. Discomfort didn’t bother him – he was on his way to the middle classes.Kumar had grown up in a village a few hundred kilometres east of Patna. His family were poor, lower-caste farmers. The village school was so basic that children sat on fertiliser sacks instead of chairs. Kumar was a bright boy, and felt driven to make something better of his life. At first he dreamed of becoming a footballer, but then decided he wanted to be an engineer, like his older cousin.In 2015 he won a place at a government-run engineering college in Rajasthan. Suddenly his life was transformed. Instead of mucking around in the dirt with the village boys he played games of badminton after class, and walked through the park at dusk with fellow students, discussing the latest films. He liked political cinema, stories which dramatised the injustices he felt as a lower-caste kid. The heroes of these films always seemed to defy the odds.They might be asked who invented JavaScript, or which element is most abundant in the Earth’s crust, or the smallest whole number for a if a456 is divisible by 11After graduating Kumar moved to Delhi to take the ferociously competitive civil-service exam, which he needed to pass in order to become a government engineer. It was a long shot, but he was determined. For a while his father sent him money to cover food and rent so that he could spend all his time preparing for the tests. After several months of this his sister got engaged and the payments stopped. Weddings are an expensive business in India, and the family could not afford to support both siblings’ futures.Kumar considered his options. He'd heard that the Ministry of Railways had many more jobs available than the civil service. Perhaps he should sit those entrance exams instead. Being an assistant train-driver wasn’t his dream. But it was a proper job, and seemed achievable.He applied in 2018, but bungled the process by failing to get the paperwork from his undergraduate degree in order. A friend suggested he wait for the next round of exams in Musallahpur Haat, a suburb of Patna where dozens of coaching centres were concentrated, and the rent was cheap. Kumar, an incorrigible optimist, felt his heart lift. He persuaded his father to scrape together an allowance that would allow him to live in Musallahpur, which was much less expensive than Delhi.

It was monsoon season when his train pulled into Patna Junction; rain poured through the metal grille that ventilated his grimy compartment. He stepped out, relieved to escape the smell of fried food and sweat, and walked up the platform past the fancier, air-conditioned coaches. These cars, which Indians call AC, have sealed glass windows and blinds. Kumar had never set foot in one. My children will do better, he thought. Once I am working on the railways, they will always travel AC.“If you are at a wedding and say you have a government job, people will look at you differently”

He had to take a rickshaw to Musallahpur – taxis refused to go there because its potholed streets were choked with students. The driver honked furiously at the waves of young people surging across their path. On the sides of the road, mountains of revision books and practice papers were on sale. It was a strange sort of student town – there were no bars, or posters plugging concerts and talks. The only events advertised in Musallahpur were practice tests. On other billboards the faces of exam coaches stared down, stern but benevolent. Behind the main drag was a labyrinth of backstreets, teeming with classrooms and libraries.About half a million students are currently preparing for government exams in Musallahpur. The intensity of cramming is the same as you might find among those preparing for the civil-service exams in Delhi, but the Musallahpur students are mostly from poor backgrounds, aiming for low-level positions.Many are taking the railway-entrance papers; some are studying for jobs in other public-sector institutions such as the police or the state banks (students often sit for multiple professions at the same time).For most government departments the initial tests are similar, and have little direct bearing on the job in question. Would-be ticket inspectors and train-drivers must answer multiple-choice questions on current affairs, logic, maths and science. They might be asked who invented JavaScript, or which element is most abundant in the Earth’s crust, or the smallest whole number for a if a456 is divisible by 11. Students have no idea when their preparations might be put to use; exams are not held on a fixed schedule.Kumar made his way to the bare, windowless room his friend had arranged for him to rent and started working. Every few days, he’d check the Ministry of Railways website to see if a date had been set for the exams. The days turned into weeks, then months. When the covid pandemic erupted he adjusted his expectations – obviously there would be delays. The syllabus felt infinite and he kept studying, shuttling between libraries, revision tutorials and mock test sessions. Before he knew it he’d been in Musallahpur nearly six years.As his 30s approached, Kumar began to worry about running out of time. There is an upper age limit for the railway exams – for the ones Kumar was doing it was set at 30. As a lower-caste applicant he was allowed to extend this deadline by three years. His parents urged him to start thinking about alternative careers, but he convinced them to be patient. His father, who was struggling to keep up the allowance, reluctantly sold some of the family’s land to help support him, and Kumar studied harder and longer.During the most recent recruitment drive there were around 90,000 positions on offer and roughly 30m people went for themLate last year, he found out from a friend that the exam had been announced. He checked the Ministry of Railways website and sure enough, there was the date: November 27th 2024. In a few weeks, the moment he’d spent his adult life preparing for would be here.Since India started liberalising its economy in the 1990s, its GDP per head has increased eightfold. The country now has the world’s fastest-growing large economy.Yet many Indian graduates struggle to find work. According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO) nearly a third of them are jobless. Walk-in interviews draw massive crowds. At the start of this year a video went viral showing thousands of engineers queuing to apply for open positions at a firm in the western city of Pune (local media reported that only 100 were available)....

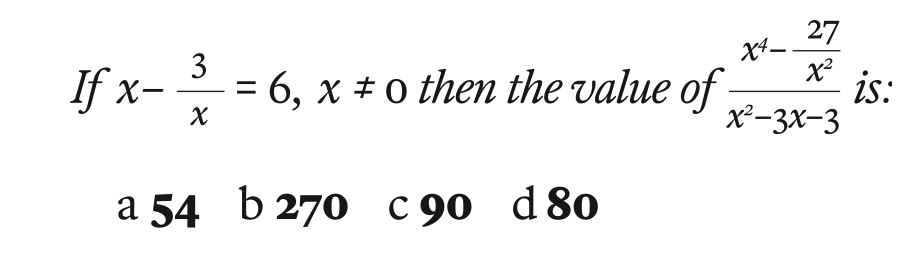

....The railway-service exams today require candidates to answer multiple-choice questions rather than write an essay. But they can still be brutally hard. Someone wanting to become an assistant train-driver could be asked:

The current affairs questions are so random that they sometimes seem designed for no other purpose than keeping people in a permanent purgatory of revision. It’s hard to know where your preparation should end when you might be asked questions such as, “Who propounded the homeopathic principle ‘like cures like’?” or “As per November 2020, how many countries have membership in the World Trade Organisation?”....

The Trump administration ended a 44-year-old legal agreement that barred a civil service exam for federal jobs, potentially reviving a practice once deemed discriminatory.

The US Department of Justice announced recently it would abandon the consent decree in Luévano v. Campbell, a 1981 deal that prompted the White House personnel office to end standardized testing for federal jobs. An administration official said the decree limited the government’s hiring practices “based on flawed and outdated theories of diversity, equity, and inclusion.”

“For over four decades, this decree has hampered the federal government from hiring the top talent of our nation,” Assistant Attorney General Harmeet K. Dhillon of the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division said in a statement.

It’s another step in President Donald Trump’s efforts to remake the federal workforce by ending what the administration views as DEI hiring practices and some anti-discrimination policies. He’s chipped away at protections for key federal officials once considered independent from the executive branch, instituted new hiring practices across agencies, and blamed tragedies such as the January plane crash at Washington Reagan National Airport on diversity-based hiring.

The Luévano case was filed in 1979—long before DEI was ubiquitous—and accused the federal Professional and Administrative Career Examination, PACE, of discriminating against non-White applicants. The consent decree prompted the government to end the test for new hires.

Disparate Impact

Angel Luévano, the lead plaintiff in that case, said in an interview he supported the Trump administration’s request for a federal judge in Washington to nullify the pact in order to stop the president’s lawyers from using his case to challenge other pillars of equal employment opportunity in government.He said the move denies the government and its allies an opportunity to challenge disparate impact discrimination—the idea that unequal outcomes can amount to bias in instances such as housing and hiring, even if the policies don’t intentionally discriminate.

“I did agree to the stipulation, but only because I wanted to stop any bad law under this administration, Luévano said. “Other parties were trying to intervene and expand the scope of the decree.”

Judge Reggie Walton, a George W. Bush appointee, accepted the stipulation and dismissed the case on Aug. 1....

—Bloomberg Law, August 5, 2025

....MUCH MORE