From the European Review of Books, Issue 9, September 2025:

Around five thousand years ago, along the northern bank of the Black Sea where the soil was rich and feather grass plentiful, the nomadic Yamnaya people sang songs about the heroes who slayed dragons. A warrior named Trito is given cattle by the gods, but this most helpful of gifts is stolen by a three-headed serpent. Fortified by an intoxicating potion supplied by the Sky-Father, Dyeus, Trito is victorious over the snake and regains his cattle. A familiar story. In the Rig Veda, the nearly 3500-year-old Sanskrit scripture, the hero Indra « slewest Vrtra the Dragon who enclosed the waters ». In the Bibliotheca, a compendium of Greek myth from the first or second century AD, Hercules « chopped off the immortal head » of the serpentine Hydra, « and buried it, and put a heavy rock on it, beside the road that leads through Lerna to Elaeus. » Snorri Sturluson in the thirteenth-century Icelandic Prose Edda describes Thor’s tussles with a serpent who « spits out poison and stares straight back from below. » The hero of the Anglo-Saxon epic poem Beowulf, « who may win glory before death », defeats the fearsome Grendel; St. George killed his dragon, too.

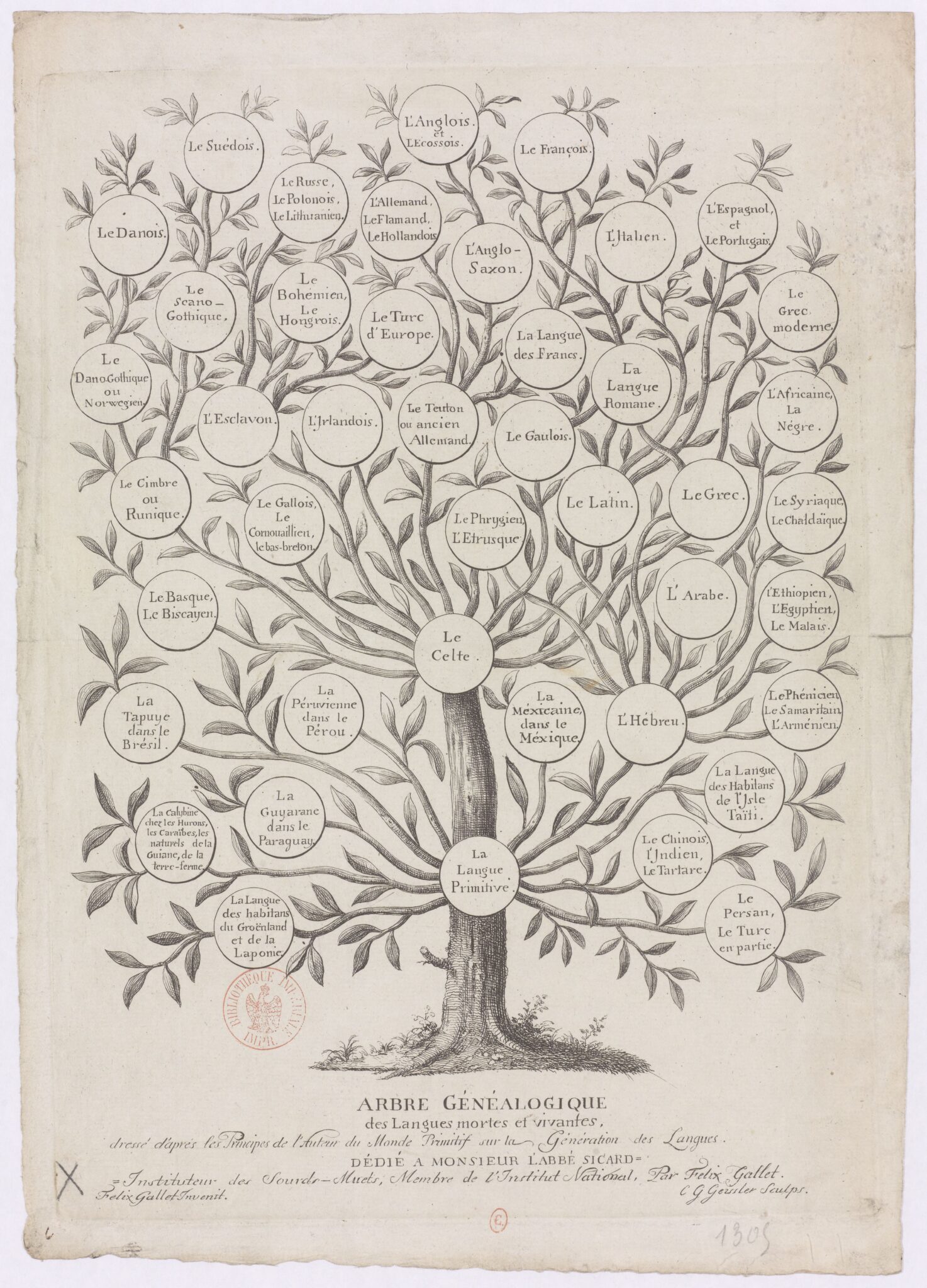

The philologist Calvert Watkins, in How to Kill a Dragon: Aspects of Indo-European Poetics (1995), used « the serpent or dragon slaying myth » to identify a common Indo-European poetics that has spread from present-day Ukraine to India and Ireland. That a variety of seemingly disparate tongues are related, from English to Urdu, has been a linguistic mainstay for generations, but that these tongues often repeated the same stories remains a wondrous fact. For centuries, scholars have speculated about these shadow storytellers at the West’s origins, but today’s advances in genetics and archaeology seem to have told us who they were and where and how they lived. And yet: there’s data, and then there are the stories we ourselves tell to interpret that data, and thereby understand where we come from. Hypothesizing a language called « Proto-Indo-European » — and then imagining a people to be called « Proto-Indo-Europeans » — has always involved myth. A disciplined mythography traces those dragons across seemingly distant and distinct cultures, to powerful effect. The imagined anthropology of these original peoples, though, has a bit of constructed fabulism about it as well.

What do the Proto-Indo-Europeans mean to us today?

The discovery and subsequent restoration of a Proto-Indo-European language that was the origin of everything from Sanskrit to Gaelic, Farsi to Welsh, Icelandic to Greek, Polish to Sardinian, Yiddish to Romani, Occitan to Norwegian, Anatolian to Catalan, is among the greatest intellectual victories of the last few centuries....

....MUCH MORE

But what have the Proto-Indo-Europeans done for us lately?