From Anton Howse' Age of Invention substack, April 22:

I had a great question in response to the last post on how coal usage first expanded in late-sixteenth-century England.

If London’s brewers had made the switch to burning coal in the 1580s, heating up water via the walls of the flue, and so preventing the brew being tainted by coal’s sulphurous fumes — a technique known as the holzer-sparungs kunst, or wood-saving art — how did this fit with another popular story, of how pale ales had arisen from brewers switching to coal much later, in the 1640s?

The answer is to do with how the heat was being used, involving two very different processes. The process in the 1580s was about using coal in the brewing itself, to boil the water ready for the malt to be mixed in. What changed in the 1640s, however, was not to do with brewing, but with the preparation of the crucial raw ingredient, the malt — grain soaked in water, allowing it to begin germinating, at which point it was dried to prevent it growing any further, and then lightly milled. Malt was a substance that brewers typically bought ready-made, so what changed was really nothing to do with brewers at all, but with with their suppliers, the maltsters.

[I thought this would be a quick and easy post to write — one I could get down in a matter of just a day, and no more than a few hundred words long. Seven weeks later, however, here we are, because it turns out that the road to mass-produced pale ale was a lot longer, more winding, and more interesting than expected, but with nobody ever having written it all up before.]

To appreciate what maltsters were trying to achieve, we first need to understand why it mattered for ale to be pale. It was essentially a sign that the malt used in making it had been dried well, and with minimal smoke from whatever fuel had been used. The smokier a malt, the worse the ale, taking on a dull, reddish hue said to “hurt and annoy the head of him that is not used thereto, because of the smoke.”1 As a physician put it in 1691, beer or ale with “a high martial colour … proves injurious to the drinkers; it sends fumes and cloudy vapours in to the crown, hurts the eyes, heats the blood, and a great friend to the stone and gravel” — that is, to kidney stones.2

There were already some longstanding ways to get around this. If malt could be dried in a hot sun, for example, as has probably been done since ale was first brewed thousands of years ago, then it was entirely smoke-free and pale. In especially windy places too, the warm summer air could be caught and directed to dry out the malt. But such conditions are relatively rare in the wet and rainy northwest of Europe, so to produce malt in any quantity, and all year round, it would have to be dried in a kiln, and by burning something — which meant there was the risk of it being infected by smoke.

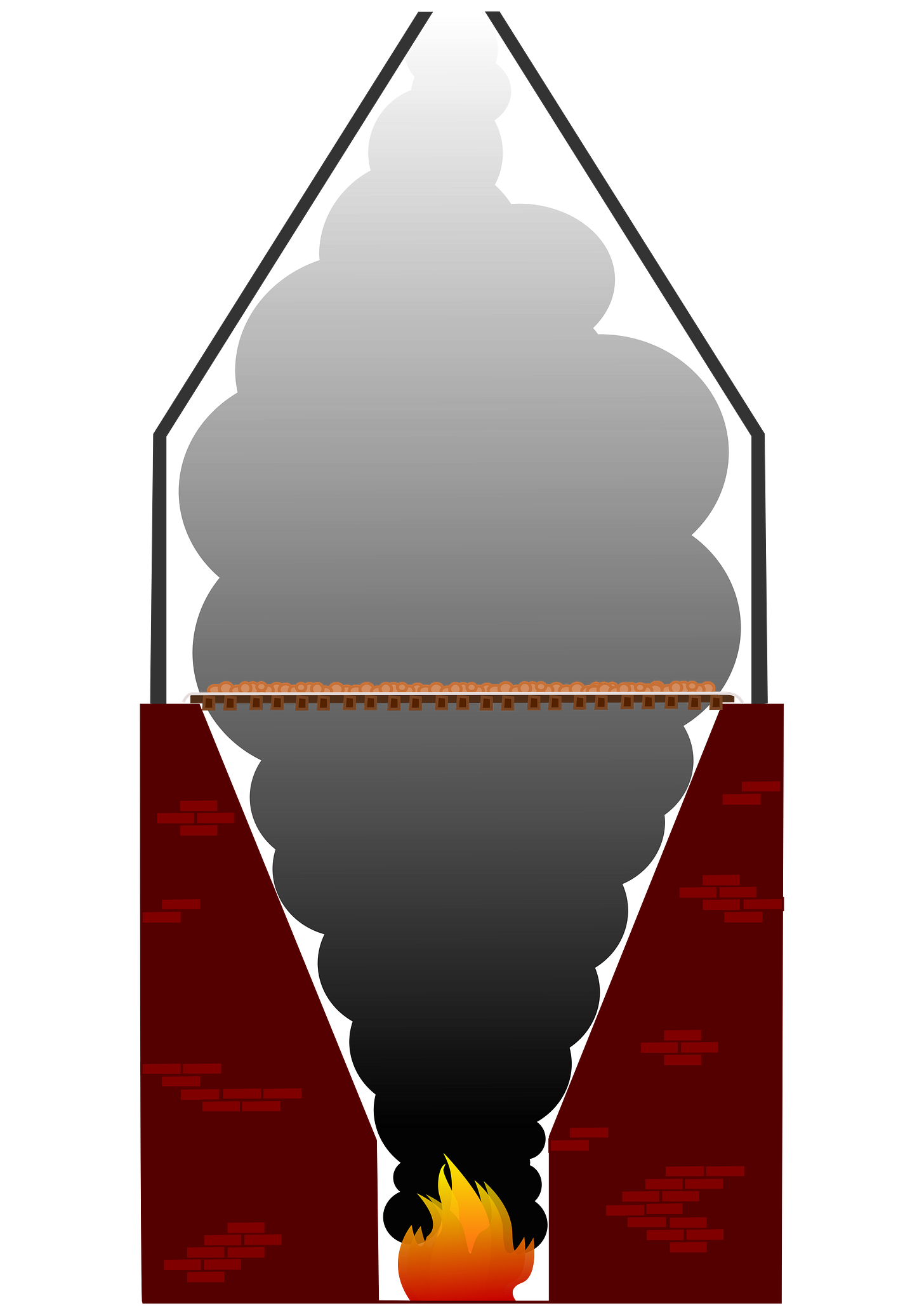

The kiln worked as follows. Once the germinating grain had been drained of its excess water, the maltster spread it evenly across a haircloth, which was placed on a mat woven of straw, wicker, or thin wooden splints. The mat was designed to allow hot air to pass up through the gaps from below, rising up through the sodden grain to carry all its moisture away. This porous mat — called the malt kiln’s “bedding”, or floor — was then placed over the top of a widening furnace flue, with the fire lit at the narrowest point some distance below.

A traditional malt kiln with an open hearth

Given the fire was placed directly beneath the grain, one of the maltster’s most important skills was their ability to manipulate heat. Unlike brewers, who merely piled on the fuel to bring liquids up to the point of boiling as quickly as possible, the maltster needed to get enough hot air through the mat and quickly enough to stop the grain from germinating any further, but not so much heat that the malt began to roast, destroying the all-important enzymes needed to convert starch into sugars when brewing. As one seventeenth-century writer put it, “too rash and hasty a fire scorches and burns it, which is called amongst maltsters ‘firefanged’; and such malt is good for little or no purpose”.3

Too large a fire could also be dangerous given it was not far beneath the highly combustible material of the kiln floor. Unattended malt kilns were a major cause of house fires, and so maltsters — usually women — were supposed to sing while they stoked the flames....

....MUCH MORE

- Old School Polish Beer Wars

- "The Lager Legacy: German Researchers Discover How a 400-Year-Old Mistake Revolutionized Beer"

- AI could make better beer. Here’s how.

- "How Beer Revolutionized Math — and Just Might Save Humanity"

- Questions America Wants Answered: "Is Craft Beer Bullshit?"

- Finnish brewery launches NATO beer with ‘taste of security’

- Now For Some Good News: "Beer still drinkable after nuclear apocalypse"

- "Divine Medicine: A Natural History of Beer"

Well, I woke up this morning and I got myself a beer

The future's uncertain and the end is always near."

Burgerbrau Keller, Nov. 9, 1923