From Politico, March 1:

A quarter-century comeback is over. Can dog parks and condos on K Street usher in a new golden age?

On Monday, D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser gathered a bunch of local leaders in a quirky independent theater to roll out ambitious plans for revitalizing downtown Washington. The $401 million initiative involves plans to boost public safety, turn office canyons into residential neighborhoods, lure campus outposts and otherwise convince the world that the nation’s capital isn’t in some sort of urban death spiral.

But while the glossy action plan — launched with speeches full of words like “visioning” — is about the future, the event may have triggered a bit of déjà vu among those with memories of the 1980s and 1990s.

Back in the decades when Washington was battling population exodus and civic dysfunction, these sorts of spectacles were commonplace: To be a city-government reporter was to be invited to a constant series of commercial ribbon-cuttings and business-district inaugurations and drug-free-zone declarations that were going to finally, finally turn things around.If you don’t recall those kinds of promises, you probably arrived during the Bush, Obama or Trump years. Thanks to a remarkable municipal comeback, newcomers to 21st-century Washington encountered a city where the challenges of affluence had replaced the specter of decay as the dominant civic storyline. Locals worried about housing costs and the emotionally fraught end of D.C.’s identity as a majority-Black city. No one spent much time fretting about whether the city itself was doomed.

Now, like an unwelcome old neighbor, the anxiety is back. The year 2023 was full of grim news. The city recorded its highest number of homicides since 1998. There were nearly 1,000 carjackings, up from 148 five years earlier. Just yesterday, a group of 70 federal lobbying and trade associations released a sharp letter to Bowser demanding action following the carjacking death of one of their own, former Trump administration official Mike Gill. Noting that other cities’ post-Covid crime waves had ebbed, the letter said Washington was “becoming a national outlier.”

The worry extends beyond crime. In December, the Metro system, still reeling from the pandemic, announced plans for drastic service cuts unless regional governments ponied up. Though the draconian proposals to permanently close 10 stations and shut the system every night at 10:00 were eventually averted, the sky-is-falling budget process didn’t do anything to help anyone’s confidence in the city’s stability.

The most symbolically freighted blow came that same month, when the owner of the Washington Capitals and Washington Wizards unveiled ambitions to move the hockey and basketball teams to the Virginia suburbs — raising the prospect that the bustling neighborhood around the downtown arena would revert to the vaguely scary nighttime desolation that prevailed before the teams arrived in the late 1990s.

In fact, you don’t need to wait for the teams to cross the Potomac in order to find desolation near the arena — even on game nights. The touristy streets in the Gallery Place neighborhood feature an abundance of empty storefronts where chains like H&M and Forever 21 once drew suburbanites — and where bars and eateries have long catered to after-work bureaucrats strolling up from the Federal Triangle. A lot of those bureaucrats now spend many of their days at home in Rockville or Herndon or Shepherd Park.

And that’s where the challenges facing today’s Washington differ from the retro storylines involving crime and suburban flight: Work has undergone an enormous change since the pandemic, a shift away from offices that’s hitting all kinds of American cities — but is especially pronounced in this most white-collar of towns.

The federal government, which used to lag the private sector in terms of allowing workplace flexibility, caught up in a hurry after Covid hit — a huge deal in a city whose roughly 200,000 federal jobs represent a quarter of the local employment base (and serve as a customer base for its service sector). And though President Joe Biden and congressional Republicans have called for the feds to get back to their downtown cubicles, the long-awaited return-to-office plans haven’t exactly brought back the old status quo: In many agencies, the requirement is that employees show up somewhere between four and eight days per pay period.

It’s not just government workers. Yesim Sayin, who pores through local data from her perch as executive director of the D.C. Policy Center, cited one particularly gobsmacking stat when we spoke this week: “Prior to the pandemic, 54 percent of lawyers in the metro area — and I’m not just talking about K Street bigwigs and lobbyists, I’m talking about probate lawyers and divorce lawyers and employment lawyers and all the lawyers in the area — worked in D.C. physically. That number is down to 32 percent right now.”

All those individual decisions to work from home add up: According to the city’s stats, annual tax revenue generation in downtown Washington is off by $243 million since 2019. Mayoral aides are warning councilmembers to prepare for a tough budget season as pandemic aid dries up.....

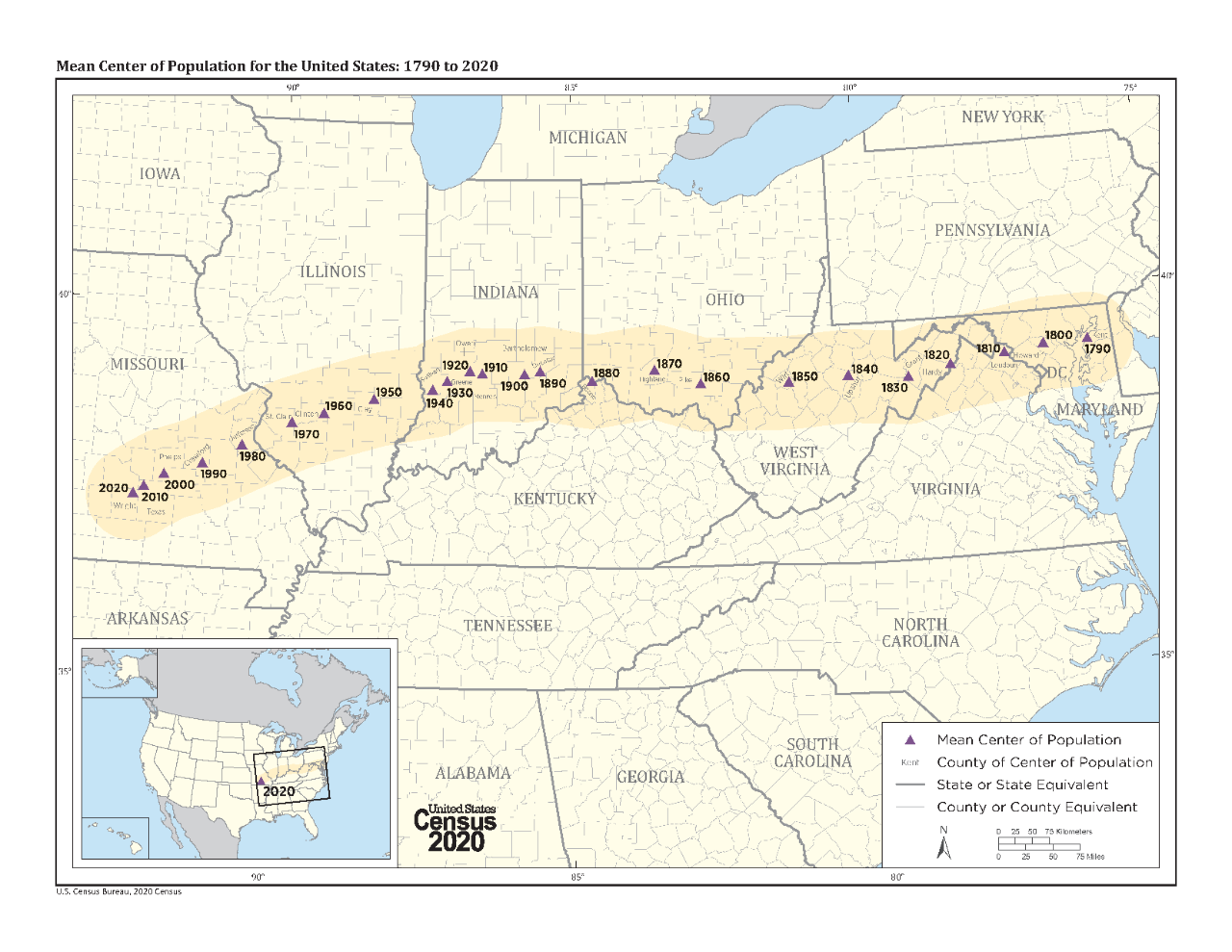

From the Bureau's dedicated Centers of Population page:

The 2020 national mean center of population is 37.415725 N, 92.346525 W, the most western and southern mean center of population point in our nation's history. The 2020 center of population is 11.8 miles from the 2010 center and 885.9 miles from the 1790 center. Hartville, Missouri, the nearest incorporated municipality to the 2020 center of population, is a town of 594 people in Wright County, Missouri.Things change and we should change with them.