From Project-Syndicate, April 14:

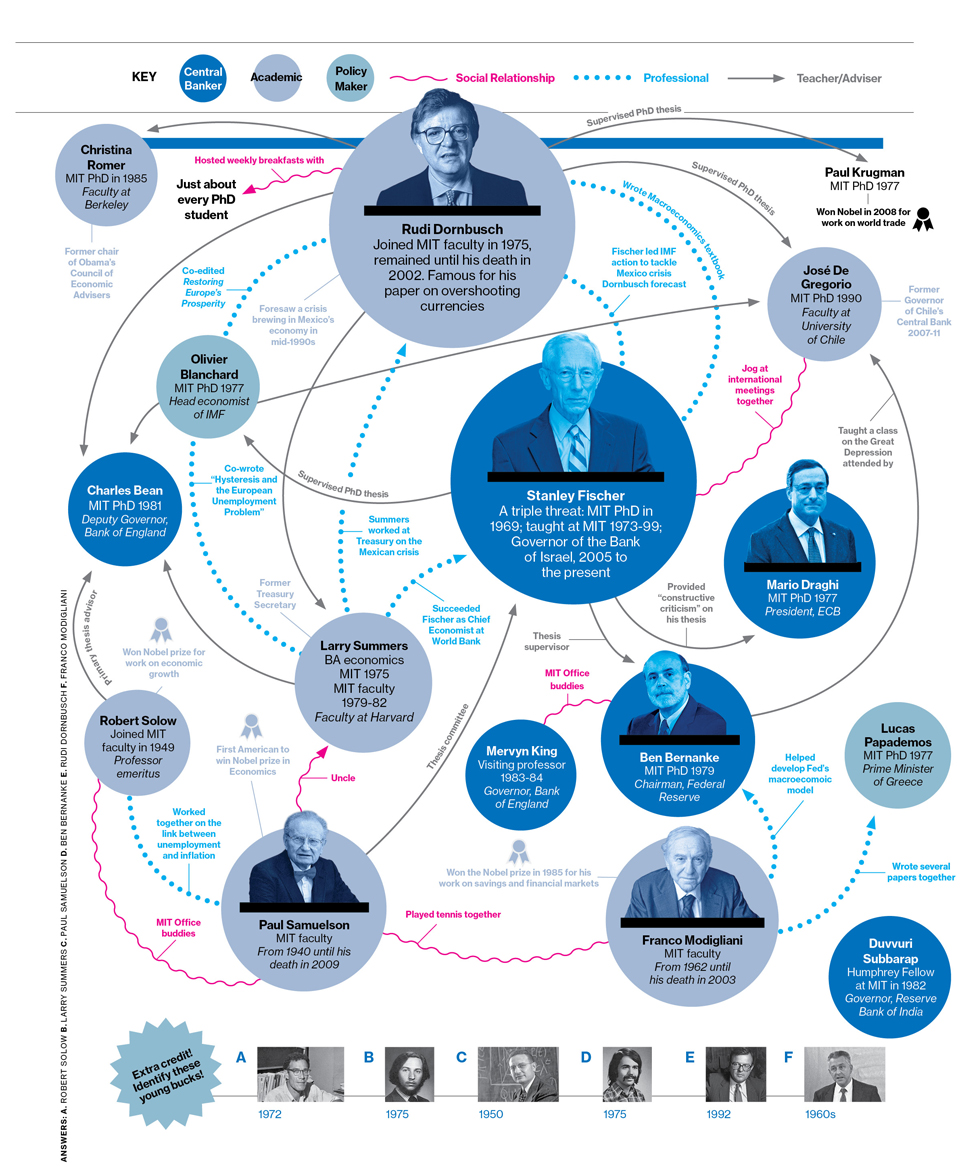

Although Keynesian economics has withstood repeated challenges and updated itself over the decades, it would be a mistake to conclude that it is sufficient for making sense of contemporary economic change. For that, we need to resurrect an alternative perspective on what money does and how it works.CHICAGO – In Money and Empire, Perry Mehrling of Boston University recounts the remarkable moment, in 1965, when Congress summoned international monetary economist and historian Charles P. Kindleberger from MIT to testify on the troubling US balance-of-payments deficit. After World War II, the United States had persistently exported more than it imported. But by 1965, the reverse was true: West German goods were flooding the US domestic market, and Japanese imports were soon to follow. With dollars flowing overseas as payment for these imports, many had begun to ask if it was time to reform the post-war Bretton Woods international monetary system, which had pegged the US dollar directly to gold and tied other currencies more flexibly to the dollar.Kindleberger’s answer was no: US trade could be financed, and the dominant international status of the US dollar secured, he argued, by an alliance of central banks led by the US Federal Reserve. “Many of my colleagues are terrified at the thought of collaboration of central bankers superseding [national] economic sovereignty and so on,” he observed. But central bankers “are technicians,” he said, “and this is the kind of problem they can handle easily.”In hindsight, Kindleberger’s comment is uncanny, considering that central banks have since become economic policymaking’s “only game in town.” Fed Chair Paul Volcker’s 1979-82 interest-rate shock, which halted the high inflation of the 1970s, was followed a decade later by the ideological and policy triumph of “central bank independence,” with Fed Chair Alan Greenspan becoming something of a financial industry folk legend.During the 2008 global financial crisis, central banks took charge again. Under Ben Bernanke, the Fed extended “swap lines” of dollar credit to other central banks around the world, and these were soon followed by “unconventional” monetary policies like quantitative easing – trillions of dollars in asset purchases over the course of more than a decade. In 2012, the president of the European Central Bank, Mario Draghi, famously backstopped the euro by pledging to do “whatever it takes” to ensure its survival.All these unconventional and extraordinary measures turned out to be merely a dress rehearsal. When COVID-19 struck, central banks unleashed even larger waves of liquidity, and most governments opened the fiscal spigots. But then came the inflationary surge of 2021, and monetary authorities have found themselves tasked once again with restoring price stability, à la Volcker.The MIT ConnectionNeither Kindleberger nor anyone else could have seen all this coming. Back in 1965, the only game in town was fiscal policy: the US economy was roaring in the wake of President Lyndon Johnson’s vaunted income-tax cut (first proposed by his predecessor, John F. Kennedy).This is also the moment that economist Alan S. Blinder chooses as the start of his A Monetary and Fiscal History of the United States, 1961-2021. In the late 1960s, Blinder was a doctoral student in the MIT economics department, where he presumably took Kindleberger’s classes in economic history. Today, Blinder warns that economics has become ignorant of its own past. Since his student days, the discipline has become more mathematical and less historical, and Kindleberger has been read less and less.Following his retirement in 1976, and until his death in 2003, Kindleberger devoted himself to writing history. According to Mehrling, “Charlie” (as he calls him) knew something fundamental about how the global economy works that many mainstream macroeconomists have never absorbed, partly because they have insisted on viewing macroeconomics within a strictly national context. Here, he has in mind those generations of economists who earned their PhDs from MIT in the decades after World War II under the supervision of lions of the discipline like Paul Samuelson, Franco Modigliani (Draghi’s doctoral adviser), or Robert Solow (Blinder’s doctoral adviser, and a member of Bernanke’s dissertation committee).Back in those days, MIT was the center of American Keynesianism, and its economics PhDs were poised to rise to powerful government positions – as Draghi, Bernanke, and Blinder’s career paths all attest. Yet, as Mehrling shows in his own subtle critique of this school, even if Kindleberger’s economics is not what men like Draghi and Bernanke profess, it is what they practiced as central bankers – thereby creating the world we live in today....

....MUCH MORE

For more on Kindleberger:

"New preface to Charles Kindleberger, The World in Depression 1929-1939"

We've visited Professor Kindleberger a few times, links below....

And on the economics gang:

"MIT economists: Automation is driving huge increases in wage inequality"

Have I ever mentioned the MIT econ. Mafia?*

-----------

*Why yes, yes I have. but it is time to say, as an intro this third or fourth go-round, that despite its remarkable assemblage of students and teachers it is no Cowles Commission (now based at Yale and set up as a foundation, under the watchful eye of Professor Shiller)....

Here's MIT: