From Cabinet Magazine's The Kiosk:

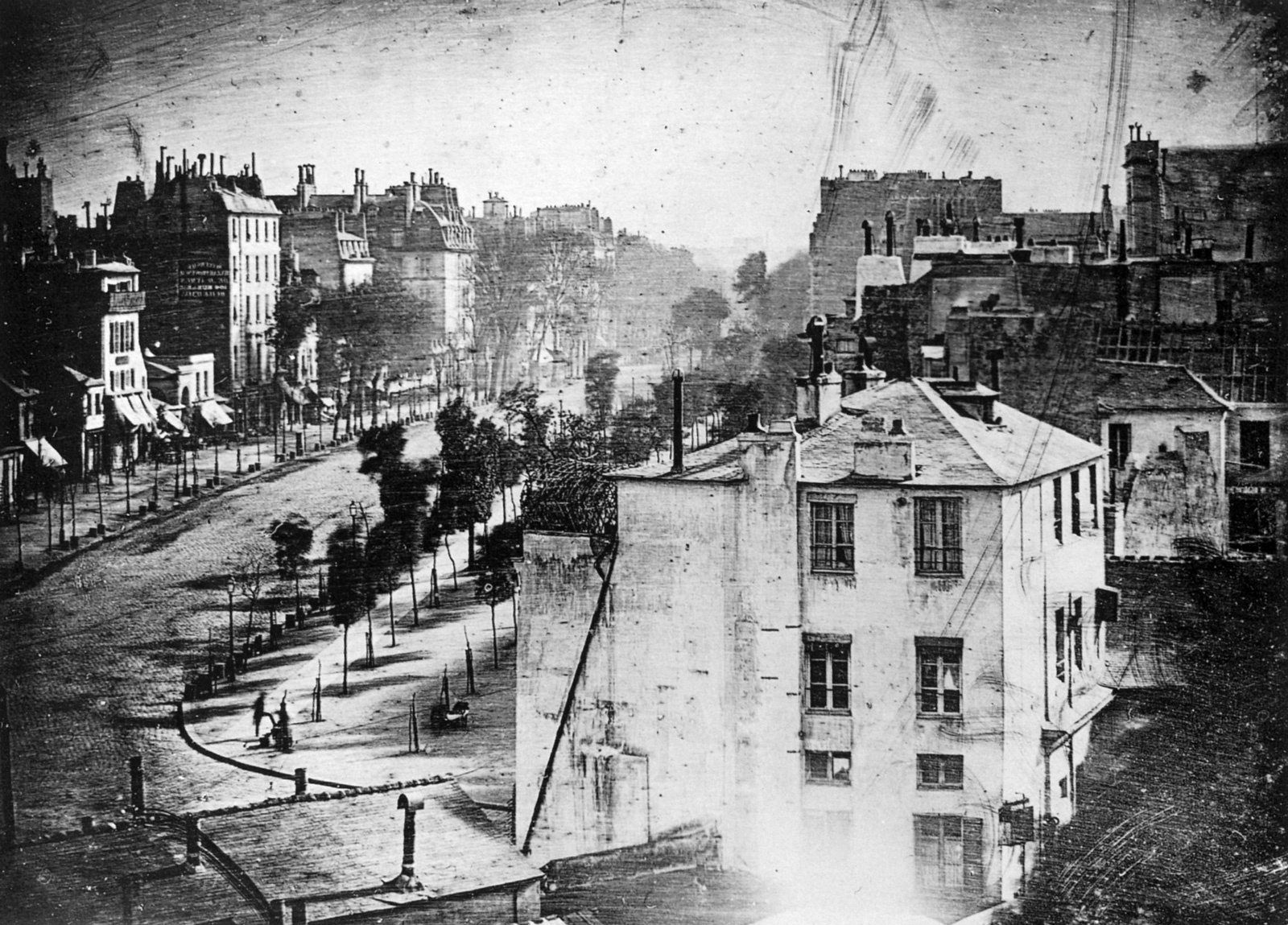

City streets seemed eerily empty in the early years of photography. During minutes-long exposures, carriage traffic and even ambling pedestrians blurred into nonexistence. The only subjects that remained were those that stood still: buildings, trees, the road itself. In one famous image, a bootblack and his customer appear to be the lone survivors on a Parisian boulevard. When shorter exposure times were finally possible in the late 1850s, a British photographer marveled: “Views in distant and picturesque cities will not seem plague-stricken, by the deserted aspect of their streets and squares, but will appear alive with the busy throng of their motley populations.”1

A crowded Broadway, 1860s. Photo Edward Anthony. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

During COVID-19 lockdowns, streets and squares truly were plague-stricken and empty. Drones buzzed over the avenues, vacant save for ambulances. Photographers stood in the middle of once-busy boulevards, taking glamour shots of the apocalypse. Although vaccines promise a return of street life, the future of urban photography may nevertheless continue to look more lockdown than lively; for several years, smartphone software engineers have been developing algorithmic methods to remove so-called “obstructions” or “distractions” from digital images, especially street scenes.2 Automated editing features, such as the Samsung Galaxy’s “Eraser Mode,” can identify moving objects—passing cars, pigeons, pedestrians—that appear in slightly different positions across a burst of photos, and the user is then able to vanish them with a swipe. The language of automated editing makes this process seem natural, as if the real picture lay behind the thing that momentarily blocked the camera’s view. The balance between appropriate subjects and extraneous distractions is established by software designers years in advance and perhaps thousands of miles away.

Editing out distractions can be accomplished in two ways. The first, more common technique is called inpainting or infill, like the method used by Eraser Mode. Once a tedious manual process in Photoshop, recently it has become automated with the software’s Content-Aware Fill tool, which uses algorithms to identify similar patterns and textures to paste into edited areas of the image. When working from a single frame, the algorithm simply assumes that the hidden area is similar to its surroundings. The second method, which is not yet in wide use, borrows the concept of a “clean plate” frame from filmmaking. Cinematographers capture several seconds of an empty scene, keeping lighting and camera angle constant, but without the actors present. In the post-production phase, the clean plate is layered under the live action sequence, so that elements of the scene can be altered easily by deleting aspects of the top layer. Applying this technique to smartphone photography would necessitate a vast archive of clean plate frames, likely focusing on popular destinations.3 Marc Levoy, a Stanford University professor emeritus who has worked on camera teams at Google Pixel and Adobe, envisions a time when distractions such as buses parked in front of the Eiffel Tower or trolley wires in San Francisco can be disappeared in the camera app, even before the photograph is taken.4 Looking through the camera app would be like augmented reality. Many of these clean plate frames already exist, although they were not intended for this use. Google’s Photo Sphere (now part of Street View), for instance, invites users to upload and share their own images, recording every aspect of the public environment, from the streets to the seaside.....

....MUCH MORE