From American Affairs Journal, Volume V, Number 2 (Summer 2021):

REVIEW ESSAY

The Rise of Carry:

The Dangerous Consequences of Volatility Suppression and the New Financial Order of Decaying Growth and Recurring Crisis

by Tim Lee, Jamie Lee, and Kevin Coldiron

McGraw-Hill, 2019, 240 pagesFor most of the twentieth century, the neoclassical synthesis in economics was generally believed to provide a solid basis for public policy. There were, nonetheless, significant dissenters. Hyman Minsky, for instance, wrote that “modern orthodox economics is not and cannot be a basis for a serious approach to economic policy.”1 In the wake of the financial crisis and the great recession of 2008, such questioning became even more vociferous, and criticisms like Minsky’s are now increasingly accepted.

The failure to incorporate finance is the most obvious lacuna of the neoclassical consensus. A greater understanding of how financial markets impact the economy is needed, but financial macroeconomists who seek to address the deficiency are rare, even at the highest levels. A decade ago, I was invited by Andrew Haldane to give an address about asset valuation at the Bank of England, where he is now chief economist. Approximately thirty to forty people attended this seminar, and afterward I remarked to Haldane that I was surprised he had been able to find so many financial macroeconomists. “I couldn’t find any,” he replied, “so I hired some financial economists and some macroeconomists and put them together.” Thus a work like The Rise of Carry, in which experienced professionals with a sound understanding of the underlying issues assess an important aspect of financial macroeconomics, is a welcome addition to the literature.

The “rise of carry” here refers primarily to the growth of the market in volatility, in which traders can hedge the stock market exposure of their individual portfolios by buying options on a volatility index. This strategy has grown dramatically in recent years and now has a significant potential to amplify systemic risks. Coupled with the misaligned compensation incentives of various financial markets participants, the rise of carry could have profound implications for market behavior as well as for macroeconomic policy.

Hedging Volatility RiskThe prices of financial assets have two key characteristics: the long-term return they provide, and their volatility, which is the extent to which that return fluctuates. Carry traders deal in market volatility. The most significant example of this is the market in the Chicago Board Options Exchange’s Volatility Index (VIX) which, as the authors observe, provides the key indicator of financial markets’ assessment of risk not just for the S&P 500 index, on which the VIX is based, but more generally. The willingness to accept risk in the bond and currency markets appears to vary with that in equities, and in each case is probably associated with the extreme ease of U.S. monetary policy. In addition, the importance of the VIX as an indicator of risk applies worldwide as well as to the United States, as the swings in international stock markets are strongly correlated and the degree to which they move together has been growing. In the authors’ words, “The S&P 500 is both the key driver of world markets and increasingly the epicenter of global carry.”

Many owners of financial assets wish at times to take out insurance against a sudden drop in asset values, and those who are worried about the U.S. stock market can buy the VIX, as its price changes with the market’s expectations about volatility, which in practice are almost identical to changes in its actual volatility. If the fluctuations in the S&P 500 index are greater than anticipated, the price of the VIX will rise and it can then be sold at a profit, thus offsetting any losses incurred as a result or in association with an increase in the market’s volatility.

The VIX is based on the prices of put and call options, which give buyers the right to sell and buy at set prices. If investors wish to protect themselves against a falling stock market they can buy a put, which entitles them to sell at any time during the life of the option at a set price. Investors can also hold cash and insure themselves against missing out should the market rise significantly by buying a call option, which allows the holder to buy a security at a set price. According to the Black-Scholes formula for option valuation, changes in the short-term value of puts and calls depends almost entirely on changes in the volatility of the return on the underlying asset.2

Unlike the stock market, which gives a positive return to long-term holders, the VIX gives a long-term negative return, as it is priced above the actual volatility of the market over the long term. This difference in price is the premium paid by those who take out insurance against a rise in volatility. In other words, the VIX’s implied volatility is greater than the actual volatility of the stock market, as it is based on option prices in which an insurance premium is embedded.

Volatility insurance differs in one important respect from other common forms of insurance (such as life, home, and vehicle insurance), which allow the specific risk of events to be pooled. In these forms of insurance, the aggregate risks taken by insurers are significantly less than the sum of the individual risks. Homeowners who buy fire insurance, for instance, pay regular premiums and are protected thereby against loss. The number of houses destroyed by fire annually does not vary much from year to year, and so the insurance industry’s total income is sufficient each year to pay for the individual costs without being at risk of significant overall loss, although profits will fluctuate as fire damage varies from year to year. But this common sort of risk pooling is not characteristic of the carry trade, in which the aggregate risk is systemic rather than specific.

Increases and decreases in the value of the Volatility Index are similar to the annual changes in total losses from fire damage, not to the specific risk that an individual house will burn down. Those who own many houses spread over different locations would find no benefit from insurance as the premiums would cost at least as much as the losses. But insurance provides a real benefit to those who own one house. Shares are different: they go up and down together. Investors reduce their risks by owning diversified portfolios of shares, but they cannot thereby avoid the systemic risk of a market crash. They can, however, do this by buying the VIX. Volatility insurance is therefore more like the reinsurance market than that for insuring individual houses, but even here the scale of the aggregate risk overshadows any similarities. Short of war, 89 percent of houses will not burn down over any given four-year period, whereas the stock market lost 89 percent of its value from its peak in 1928 to its trough in 1932. As Henry Kaufman wrote in his autobiography, “financial options create risks that cannot be hedged perfectly without, in effect, undoing the transactions altogether.”3

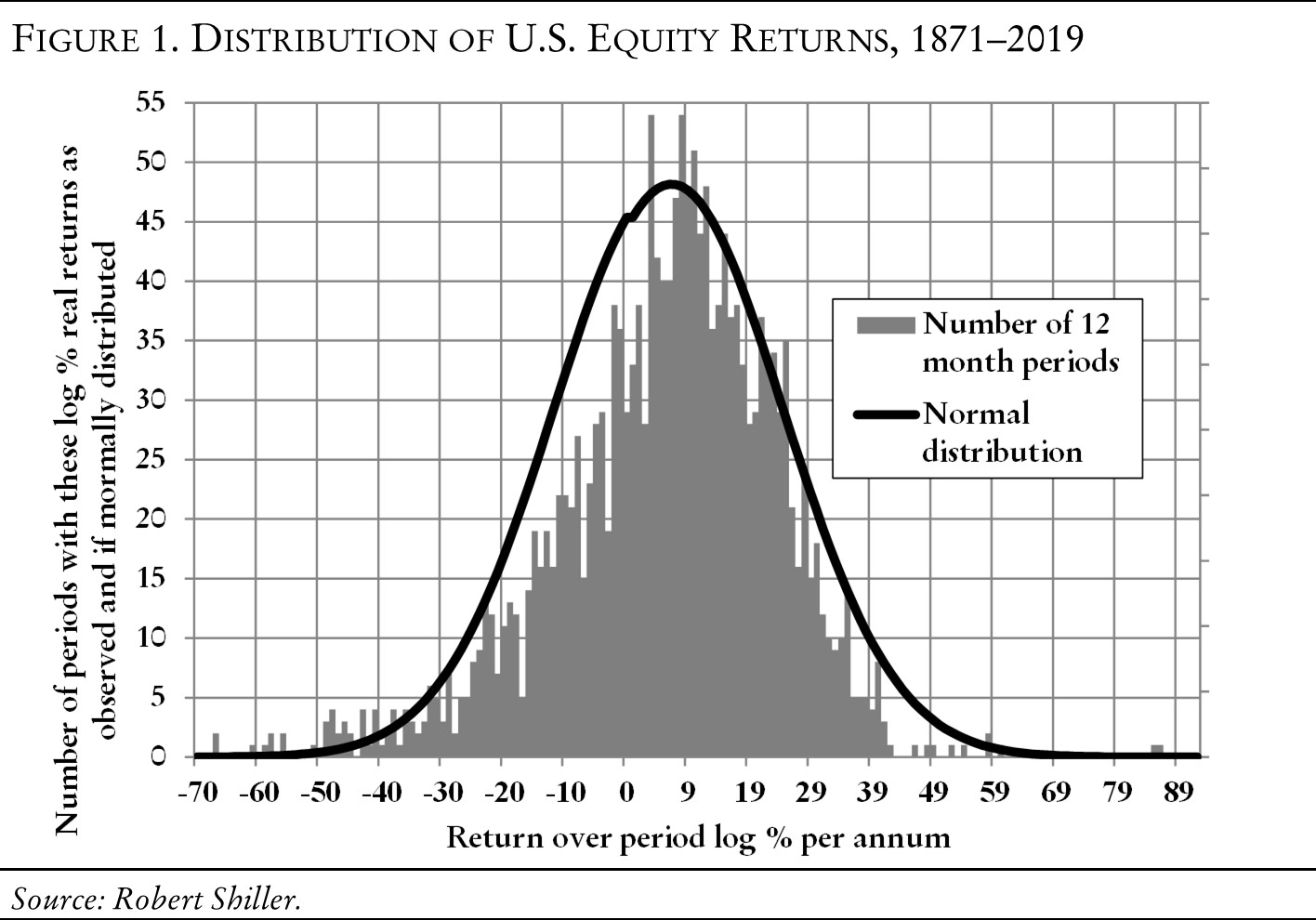

Investors who insure against volatility usually want protection from sharp drops in share prices, which are closely correlated with increases in market volatility. As shown in figure 1, the actual pattern of equity returns is not quite a normal distribution, in which rises and falls are symmetrical. There are more years in which returns are above average than years in which they are below average, and there are more bad years with extreme results than good years. This pattern of returns can be closely represented by two normal distributions in which the market gives an above-average return 90 percent of the time but a negative return in the remaining 10 percent.4

These characteristics are reflected in the options market on which the VIX is based. As both put and call options provide the same cover against market volatility, the prices of the two exhibit a phenomenon known as “put-call parity,” diverging little from each other.

Buying puts and calls is possible only because investment banks and others are prepared, for a consideration, to take on the risk of selling options. They in turn wish to avoid the losses that result from market fluctuations. In the case of small changes in the market, this is achieved through a process known as “delta hedging.” This involves dealing in the cash market (buying and selling the underlying equities) with its associated costs, as The Rise of Carry explains in detail. If the price of the underlying security changes, the price of the option will also change (by an amount usually represented by the Greek letter Δ). The relationship between the change in the option price and the change in the stock price is stable for small fluctuations. Sellers of options can thus hedge against loss by taking a position in the stock opposite to the risk they have assumed on the option. For instance, if they will lose money on a call option in the event that the stock price increases, then they buy the amount of the stock which will give them an equal profit from that same increase. This amount must equal Δ times their exposure on the option. But losses cannot be avoided in this way when price changes are too large.

Stephen Wright and I provided an example of how the process of delta hedging works in a 1997 report.5 The example we gave was for prices on July 10, 1997, but the same basic arithmetic applies today. At the end of 2020, when the S&P was at 3,695, one-month put and call options with a 3,695 exercise price had almost exactly the same exposure to the risk of small changes (the same delta), in opposite directions, and very similar prices of around $80. A dealer selling a thousand of each would have had liabilities of around $16 million (2,000 × 80 × 100 options per contract) and would be more or less perfectly delta hedged. If the market had fallen by 1 percent, the price of the put would have risen and that of the call would have fallen by around $18, leaving total liabilities little changed. In the case of larger movements, the situation would have been very different, however. If, for example, the market had fallen by 10 percent, the call would have become essentially worthless, while the put would have been worth around $360, roughly the difference between the exercise price and the new stock price. The liabilities of the option dealer would therefore have increased from $16 million to $36 million (1,000 × 360 × 100).

Thus options traders have “gamma exposure,” which is the risk that volatility will increase. But the VIX market provides a counterbalance: individual traders who buy the VIX profit from rises in the market’s volatility and can therefore hedge against the gamma risk. Delta and gamma do not comprise all the risks which options dealers incur; for example, they cannot collectively hedge their exposure to the market’s own estimate of volatility, known as “vega exposure.” Likewise, the Black-Scholes formula does not account for all risks, so traders use highly complex and proprietary computer programs to maximise profits and reduce their risks. As Henry Kaufman has noted, “dynamic hedging is an inexact science, one that relies on extraordinarily complex computerized models, which themselves are far from infallible (because they are built on historical data).”6

With fire insurance, the risk that any one house will burn down is specific to each owner and the companies who provide insurance to many householders do not bear this specific risk but, if they charge enough to cover the average risk of houses being destroyed, they are only at risk if that average is volatile. If it is, they incur some systemic risk, but for houses this is very low except in wartime, which is therefore usually excluded in insurance policies. The stock market differs from fire and motor insurance in that its volatility, against which the VIX provides insurance, is itself very volatile, as illustrated in figure 2. Moreover, the pattern is one of long-term rather than short-term fluctuations. As a result, there is, in practice, no market for insuring against long-term falls in share prices. The VIX is for one month and the risk of sharp falls over this period are systemic rather than specific. Thus, as Henry Kaufman remarks, the risks of the option market cannot in practice be hedged away; they must be borne by somebody.....

....MUCH MORE

Michael Nahm, Ph.D. Freiburg, Germany

The (re-)emergence of normal or unusually enhanced mental abilities in dull, unconscious, or mentally ill patients shortly before death, including considerable elevation of mood and spiritual affectation, or the ability to speak in a previously unusual spiritualized and elated manner....