By Raphael Bostic, president and chief executive officer of the Atlanta Fed

Over the past few months, I have been asked one question regularly: Why is the Fed removing monetary policy stimulus when there is little sign that inflation has run amok and threatens to undermine economic growth? This is a good question, and it speaks to a philosophy of how to maintain the stability of both economic performance and prices, which I view as important for the effective implementation of monetary policy.

In assessing the degree to which the Fed is achieving the congressional mandate of price stability, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) identified 2 percent inflation in consumption prices as a benchmark—see here for more details. Based on currently available data, it seems that inflation is running close to this benchmark.

The Fed's other mandate from Congress is to foster maximum employment. A key metric for performance relative to that mandate is the official unemployment rate. So, when some people ask why the FOMC is reducing monetary policy stimulus in the absence of clear inflationary pressure, what they really might be thinking is, "Why doesn't the Fed just conduct monetary policy to help the unemployment rate go as low as physically possible? Isn't this by definition the representation of maximum employment?"

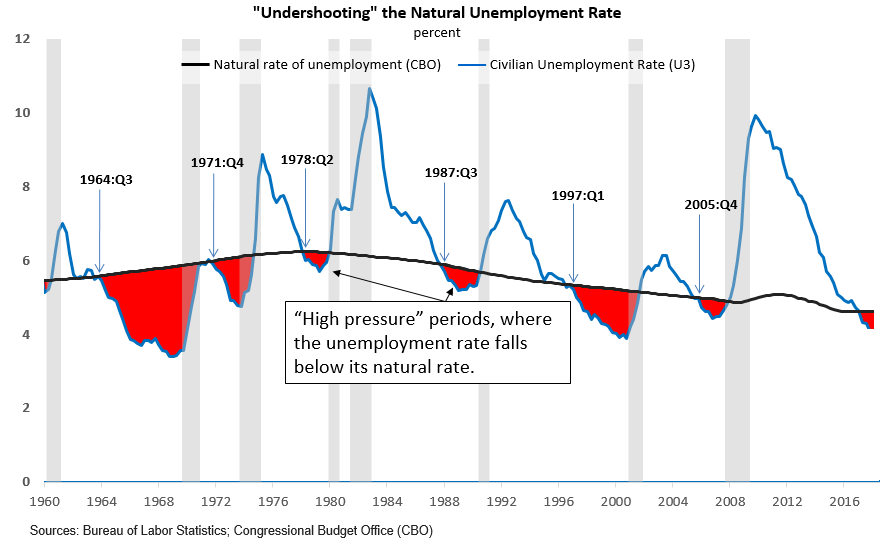

While this is indeed one definition of full employment, I think this is a somewhat short-sighted perspective that doesn't ultimately serve the economy and American workers well. One important reason for being skeptical of this view is our nation's past experience with "high-pressure" economic periods. High-pressure periods are typically defined as periods in which the unemployment rate falls below the so-called natural rate—using an estimate of the natural rate, such as the one produced by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO).

As the CBO defines it, the natural rate is "the unemployment rate that arises from all sources other than fluctuations in demand associated with business cycles." These "other sources" include frictions like the time it takes people to find a job or frictions that result from a mismatch between the set of skills workers currently possess and the set of skills employers want to find.

When the actual unemployment rate declines substantially below the natural rate—highlighted as the red areas in the following chart—the economy has moved into a "high-pressure period."

For the purposes of this discussion, the important thing about high-pressure economies is that, virtually without exception, they are followed by a recession. Why?......MORE