From shipwrecks to Couto Mixto, Galicia has long been home to contraband.

t seemed hard to believe when we did the measurements at school: Galicia has 930 miles of coast. More than Andalusia, more than all of the Balearic Islands put together. Zoom in and the shoreline reveals an aversion to straight lines; it comprises an uncompromising welter of recesses and tiny bays, ideal for entering and leaving unseen. The succession of shelves and rocks that skirt it could almost have been designed for ships to run aground on. One of its stretches is called Costa da Morte—the Coast of Death. And it is on the Costa da Morte that this story begins.

There was a time when the only interaction between the villages and towns in the area—most of them nestled away, sheltered from the scouring Atlantic winds—took the form of rivalries between the fishermen’s guilds. The remoteness of Galicia brought about a unique accent that other Spaniards often struggle to understand. The jewel in the crown is Cape Finisterre—the end of the world as far as the Romans were concerned; to the Greeks the point from which Charon the ferryman set off across the Styx; and the place where the Christian Camino de Santiago begins. For most visitors today, it is simply a charming promontory jutting into the ocean. And, it just so happens, a nice steep headland for bringing in contraband.

The people of Costa da Morte, which runs roughly from the city of Coruña to a little way past Finisterre, have always depended on the sea for their livelihood. On fishing and on trade, but also on passing merchant vessels; they would not always wait to get their hands on the cargo at the principal ports of Corme, Laxe, Muxía, or Camariñas, often choosing to go out raiding instead. Or they could just keep an eye out for any wreckage that might wash ashore.

Any attempt to count the ships that have sunk off Galicia is itself destined to flounder. There have been 927 documented cases since the Middle Ages—“If only,” locals say to that. A researcher named Rafael Lema has written a meticulous compilation of these stories entitled Costa da Morte, un país de sueños y naufragios (Coast of Death: Country of Dreams and Shipwrecks), which summarizes some of the most surprising incidents.

At the end of the nineteenth century, the English merchant vessel Chamois ran aground near Laxe. According to local fable, a fisherman went to the aid of the crew, calling out when he drew close to see if the captain wanted assistance. The captain, thinking he was being asked the ship’s name, answered “Chamois,” and a wondrous linguistic short circuit resulted: the fisherman understood him to be saying that the ship’s cargo was cattle (bois in Galician) and hurried back to land to tell his compatriots. In no time at all they had sailed out in their hundreds, armed to the teeth—to the horror of the bedraggled Englishmen.

Around the same time there was the Priam: when it ran aground, the gold and silver watches that spilled onto the beach were gone within a matter of hours. A grand piano also washed up, and the locals, mistaking it for another chest, hacked it to pieces. They had never laid eyes on such a thing before.

The popular story of the Compostelano does not strictly concern a shipwreck. She maneuvered expertly to enter the River Laxe and, coming to landfall, ran into a sandbank off Cabana beach. When the locals went down to take a look, they are said to have found a cat on board but no sign of any crew.

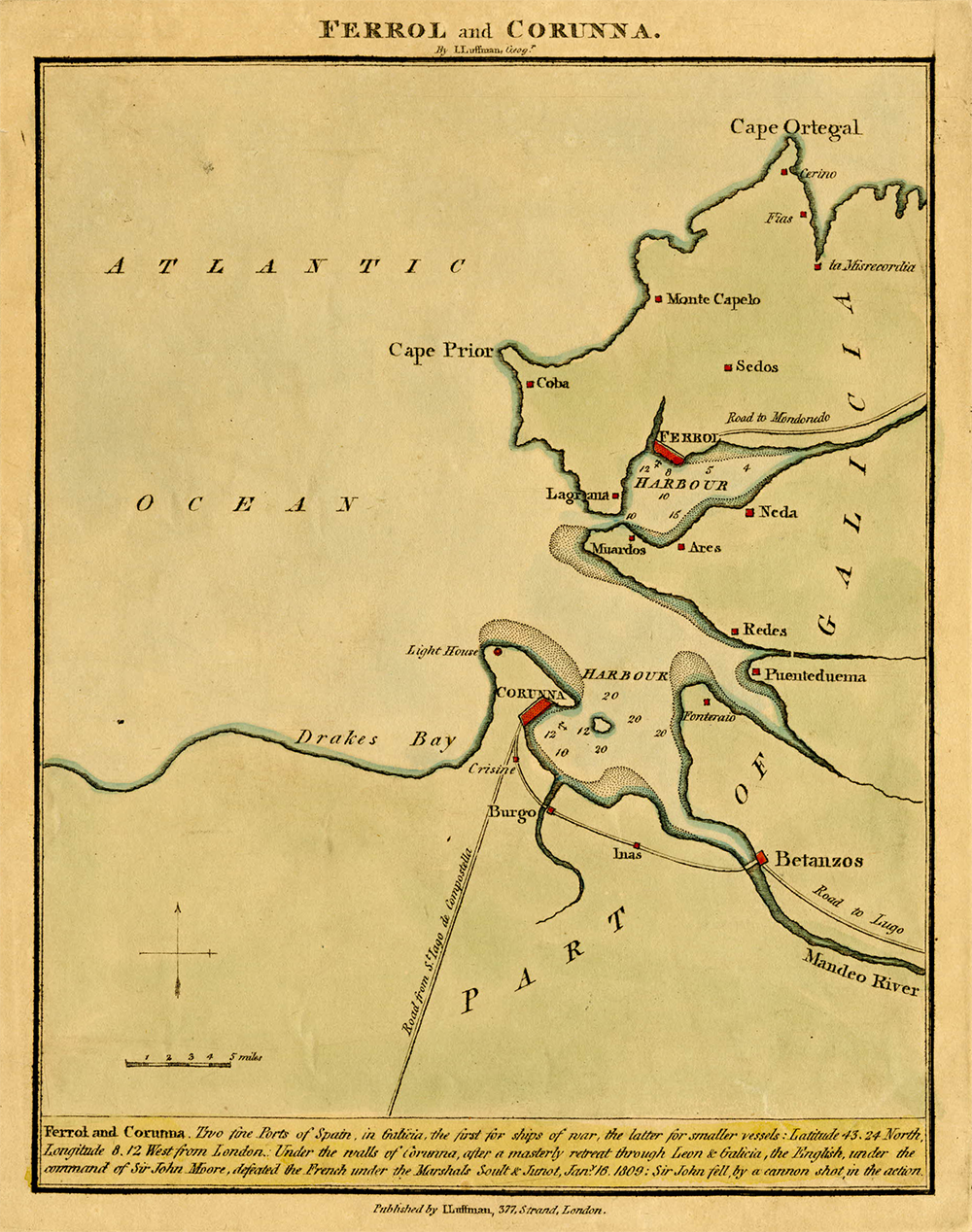

Map of part of Galicia showing the harbors of Ferrol and Corruna, by John Luffman, c. 1809.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

One of the worst tragedies took place in 1890, when the English vessel Serpent went down off Camariñas and its crew of five hundred perished. Their graves can be found in the nearby English cemetery, positioned scenically between beach and cliff. Twenty years earlier the Captain had sunk off Finisterre, and no fewer than four hundred men lost their lives.

The horror of shipwrecks did not always take the shape of drowned men. In 1905 the Palermo, its hold full of accordions, sank near Muxía. The onshore breeze was said to carry chilling, ghostly strains that night.

In 1927 the Nil beached near Camelle, its hold full of sewing machines, fabrics, carpets, and wagon parts. The first thing the ship owners did was to employ some local people to guard the cargo. Little good that did: others came and stripped the vessel in a matter of days. The Nil also happened to be carrying boxes of condensed milk. According to the accounts, the locals had never seen condensed milk before, and mistook it for paint. When they took it home and began daubing it on their houses, an infestation of flies followed that was of biblical proportions.

The instances outside living memory also include the staggering 1596 case of the Spanish Armada: twenty-five vessels sunk, at a cost of more than 1,700 lives. Reports at the time paint the direst of pictures, with bursts of lightning illuminating a watery scene littered with corpses, shattered pieces of ships, and men crying out as the waves claimed them....MUCH MORE