Keep an eye on this stuff, opportunity lurks,

From Knowable Magazine, January 9:

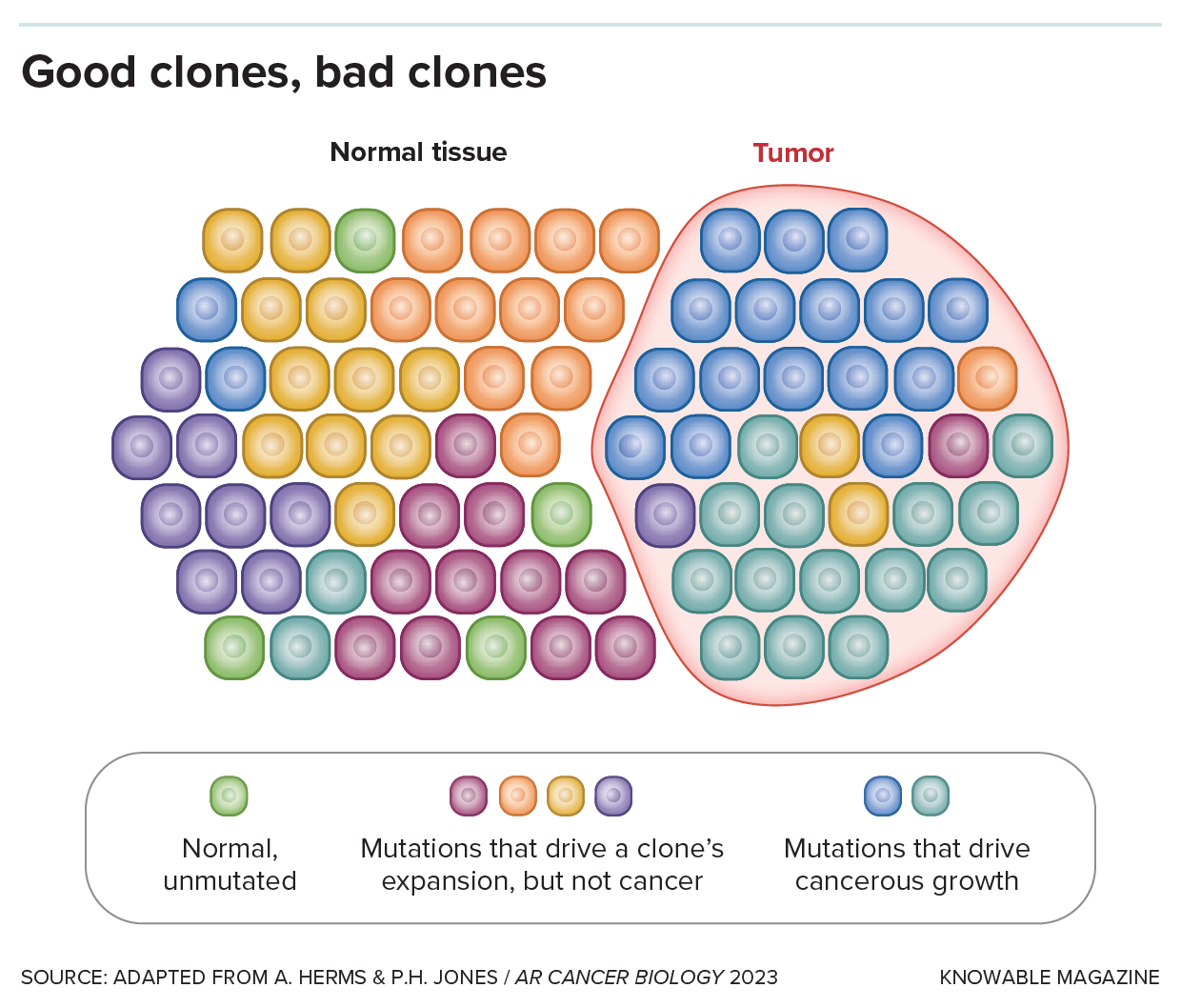

We are all mosaics

Picture your body: It’s a collection of cells carrying thousands of genetic mistakes accrued over a lifetime — many harmless, some bad, and at least a few that may be good for you.

You began when egg and sperm met, and the DNA from your biological parents teamed up. Your first cell began copying its newly melded genome and dividing to build a body.

And almost immediately, genetic mistakes started to accrue.

“That process of accumulating errors across your genome goes on throughout life,” says Phil H. Jones, a cancer biologist at the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Hinxton, England.

Scientists have long known that DNA-copying systems make the occasional blunder — that’s how cancers often start — but only in recent years has technology been sensitive enough to catalog every genetic booboo. And it’s revealed we’re riddled with errors. Every human being is a vast mosaic of cells that are mostly identical, but different here or there, from one cell or group of cells to the next.

Cellular genomes might differ by a single genetic letter in one spot, by a larger lost chromosome chunk in another. By middle age, each body cell probably has about a thousand genetic typos, estimates Michael Lodato, a molecular biologist at the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School in Worcester.

These mutations — whether in blood, skin or brain — rack up even though the cell’s DNA-copying machinery is exceptionally accurate, and even though cells possess excellent repair mechanisms. Since the adult body contains around 30 trillion cells, with some 4 million of them dividing every second, even rare mistakes build up over time. (Errors are far fewer in cells that give rise to eggs and sperm; the body appears to expend more effort and energy in keeping mutations out of reproductive tissues so that pristine DNA is passed to future generations.)

“The minor miracle is, we all keep going so well,” Jones says.

Mutations that promote expansion of clones can be dangerous cancer drivers but can also be neutral

or even beneficial mutations that maintain the integrity of a tissue and do not promote cancer.

Scientists are still in the earliest stages of investigating the causes and consequences of these mutations. The National Institutes of Health is investing $140 million to catalog them, on top of tens of millions spent by the National Institute of Mental Health to study mutations in the brain. Though many changes are probably harmless, some have implications for cancers and for neurological diseases. More fundamentally, some researchers suspect that a lifetime’s worth of random genomic mistakes might underlie much of the aging process.

“We’ve known about this for less than a decade, and it’s like discovering a new continent,” says Jones. “We haven’t even scratched the surface of what this all means.”

Suspicious from the start

Scientists had suspected since the discovery of DNA’s structure in the 1950s that genetic misspellings and other mutations accruing in non-reproductive, or somatic, tissues could help explain disease and aging....

....MUCH MORE