From American Affairs Journal, Volume VIII, Number 1, Spring 2024:

Since I last wrote in detail on the topic of China’s domestic semiconductor industry in early 2021,1 the landscape has changed considerably. The Biden administration has continued to impose export control restrictions on Chinese firms, and the October 7, 2022, package of controls targeted not only advanced semiconductors (such as GPUs used for running artificial intelligence and machine learning workloads) but also expanded significantly on controls over semiconductor manufacturing equipment (SME).2 One goal of the U.S. controls is to prevent Chinese firms from moving into nonplanar technology processes, such as FinFET and eventually Gate All Around (GAA). The new restrictions included novel end-use controls and controls on U.S. persons, posing major new challenges for China’s domestic semiconductor industry development going forward.3 Updates to the October 2022 controls released on October 17, 2023, followed this approach, and introduced more challenges for China’s semiconductor industry. To an extent not apparent in 2021, the long-term ability of Chinese firms to source advanced semiconductors is now much more closely tied to the speed of development of China’s domestic toolmaking and manufacturing capabilities, given the substantial increase in the number of Chinese design firms now unable to use foreign foundries.

U.S. controls are impacting only cutting-edge capabilities, so Chinese firms will continue to expand capacity at mature nodes where the bulk of the domestic demand remains. At more advanced nodes below 28 nanometers, leading Chinese firms continue to have access to some advanced Western tools, particularly deep ultraviolet (DUV) immersion lithography systems, that they will continue to use for as long as possible to stretch logic production at more advanced nodes, particularly down to 7 and even 5 nanometers. Nevertheless, it is important to note that using DUV tools for advanced node production is complex, because using techniques like multi-patterning also requires advanced capabilities in other key tools such as deposition and etch. For advanced node production, tight coupling of key processing tools is required, and the issue is not just about lithography tools, as media and other commentary on China’s semiconductor industry typically emphasizes. Materials such as photoresists are also critical to the process of extending DUV capabilities to fine feature lengths at 7 nanometers and below.

Even though U.S. controls have so far focused on advanced manufacturing capabilities, Beijing and Chinese companies are also worried about future controls, and will prioritize tool and material production lines free of Western inputs to reduce long-term risks. Hence, even if they can still acquire Western tools, virtually all leading Chinese foundries and memory companies are working methodically with domestic toolmakers to develop and validate equipment to eventually establish production processes largely free of Western equipment. This will be a multistage, multiyear process, starting with 40 nanometers and proceeding quickly, likely this year, to 28 nanometers, and then 14, 12/10, and eventually 7 nanometers. Continued access to Western tools such as DUV—coupled with some foreign and increasingly domestic etch and deposition tools—can provide a bridge to an all-domestic future for Chinese semiconductor manufacturing. From an overall semiconductor industry viewpoint, what is happening in China will fundamentally change the industry over the next decade.4

In addition, officials in Beijing are developing new approaches to public-private collaboration to push innovation on key technologies, such as advanced lithography. Beijing, working closely with the private sector, is looking to overcome bottlenecks by easing the transfer of advanced state-backed R&D to designated private sector companies, by pushing companies to work together on critical technologies, and by pursuing approaches that have been successful in other sectors. These approaches include having a large state-owned firm play a leading role in the sector while funding and facilitating multiple teams to tackle tough problems, as was done for exascale computing.5

Many other pieces of the semiconductor manufacturing industry are also targets of renewed efforts to build domestic Chinese alternatives, such as design tools, advanced materials, advanced packaging techniques, and systems engineering approaches designed to improve performance via a systems-led approach, rather than relying solely on process-node improvements. All of these approaches will be important for China’s domestic capabilities going forward, particularly packaging, including chiplet design and 2.5 and 3-d back-end packaging approaches, that will feature in system engineering efforts to improve performance levels and bridge to new, domestic-only production processes.

None of this will be easy or guaranteed to succeed, in the sense of producing end products comparable to those of the mainstream global semiconductor manufacturing process. These efforts will also produce winners and losers, with Western tool makers perhaps the biggest victims as they are gradually frozen out of what had been a huge, growing, and lucrative market that they dominated before October 7, 2022. Still, parts of China’s semiconductor sector will retain greater linkage with global developments and supply chains than others, and the overall situation will continue to be complex and evolving.

Sweeping Controls on Tools Target China’s

Domestic Manufacturing IndustryWhen Secretary of State Antony Blinken put technology competition at the center of U.S.-China relations and competition in May 2022,6 few likely realized the extent of what was to follow later that year. In the fall of 2022, the Biden administration, for the first time, had senior officials articulate the U.S. strategic policy toward semiconductors and China, as expressed by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan and other senior officials, such as Undersecretary of Commerce Alan Estevez. The “Sullivan Doctrine,” as articulated in late 2022, includes several parts, starting with Sullivan’s assertion that the United States intends to maintain an absolute lead over China in key sectors, rather than a sliding scale. He also indicated that the United States was implementing a “small yard, high fence” approach toward China and advanced technologies,7 and further asserted that technologies such as advanced computing (semiconductors as well as AI, machine learning, and high-performance computing), biotechnology, and green/clean technology were “truly force multipliers” throughout the tech ecosystem. The Sullivan Doctrine’s bottom line: leadership in each of these areas is a “national security imperative.”8

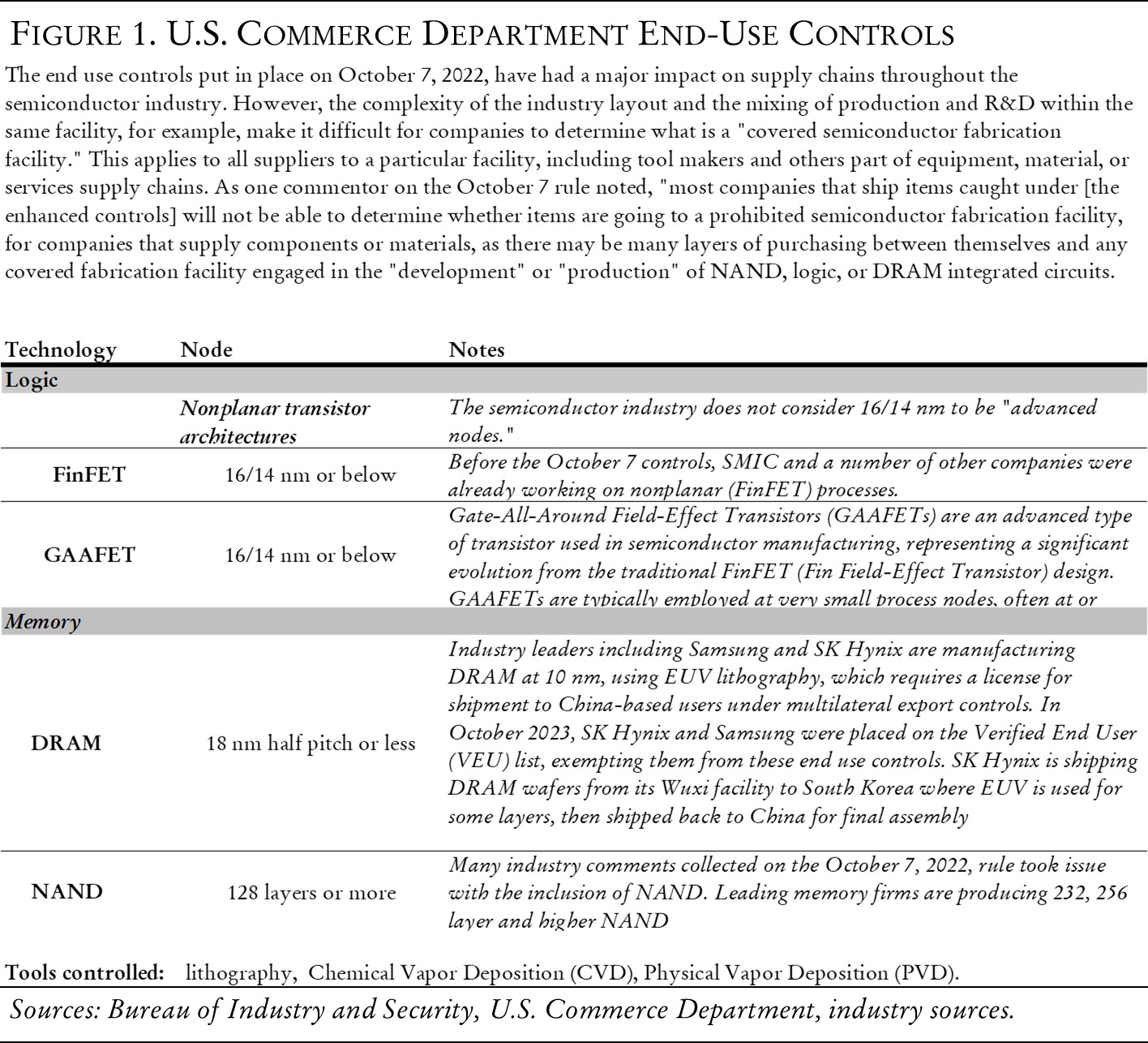

The most complex and controversial portions of the October 7, 2022, rules released by the Commerce Department9 were the end-use controls on semiconductor manufacturing tools, and on U.S. persons. The SME controls call for licensing of equipment and U.S. persons for manufacturing of logic semiconductors at 16/14 nanometers, 3-d NAND memory at 128 layers, and DRAM at 18 nanometers half pitch. The result of these controls, initially dropped unilaterally, without agreement from other key countries whose companies occupy critical portions of the SME supply chain—namely Japan and the Netherlands—was that leading U.S. toolmakers, such as Applied Materials, KLA Tencor, and Lam Research were forced to pull all their U.S. personnel from facilities in China, particularly at foundry leader SMIC, NAND memory giant YMTC, and DRAM major CXMT. In addition, the package of restrictions also imposed controls on inputs to Chinese domestic semiconductor equipment makers, in a bid to keep them from replacing foreign equipment leaders. Almost overnight, the entire Chinese domestic manufacturing and toolmaking equipment sector was thrown into a completely new era.

The October 2023 update10 to these rules has only added to the challenges Chinese semiconductor firms face. The new controls tightened thresholds around specific parameters used for some much older ASML DUV lithography tools, again moving the goalposts. The 2023 package also raised thresholds for performance of advanced GPUs that could be sold to Chinese end users, capturing a number of GPUs that global leader Nvidia had redesigned for the China market to comply with restrictions in the 2022 package.

For China’s domestic industry, the most important impact of the controls was to massively incentivize designing U.S. technology out of the semiconductor space, by both Chinese domestic and foreign firms. Prior to this, Chinese technology firms acquired and used the most advanced equipment and services available, like their peers and competitors globally. Many observers still erroneously claim that China’s Made in China 2025 strategy (announced in 2015) was a signal that Beijing wanted to go it alone in key sectors. A side-study linked to Made in China 2025 listed wildly unrealistic goals for domestic proportions of different types of semiconductor production, but this hardly represented a concerted government policy, and Chinese semiconductor companies largely ignored it. That changed in 2023. Senior Chinese semiconductor industry experts stress that domestic industry players would prefer to use the best available tools, but are now under increasing pressure to favor domestic firms and develop alternative supply chains.11

Chinese Reactions to New U.S. Controls

As the events of October 2022 began to play out in China and around the world, and Chinese industrial planners, company executives, and foreign partners assessed the damage, several critical issues emerged that will determine the future direction of China’s semiconductor industry.

First, the unilateral nature of the controls has necessitated a long and painful dialogue between the U.S. government and the governments of the Netherlands and Japan around how to align on the controls. This so-called trilateral group had been discussing controls on SME for nearly two years, but both Japan and the Netherlands preferred setting any end‑use controls at more advanced nodes, at 10 nanometers or below. When the U.S. side set the end-use controls at 16/14 nanometers, the trilateral talks broke down. U.S. officials were apparently under pressure from the Department of Defense, which had grown concerned by reports over the summer of 2022 that SMIC had been able to produce semiconductors with some layers at 7 nanometers—using existing deep ultraviolet (DUV) lithography gear and other foreign and domestic tools such as etch and deposition. This was one of many instances in which the U.S. semiconductor industry felt that the Biden administration was “moving the goalposts” around the parameters for controls on technology for Chinese end users.12

The U.S. government badly underestimated the political and industry pushback on the unilateral controls. All talk of a “trilateral agreement” was quickly dropped, and privately, U.S. officials began speaking more about “leveling the playing field” and “burden sharing.”13 Neither the Japanese nor Dutch governments wanted to be part of an agreement visibly directed at containing China’s technology ambitions, and both governments have received major pushback from their leading semiconductor firms. At the same time, neither the Japanese, the Dutch, nor the toolmaking industry were expecting memory to be included in the controls....

....MUCH MORE