Oft expectation fails, and most oft thereAbout the title. It is drawn from the subject heading under which, in the catalogue of the New York Public Library, appears a single and singular item: the periodical British Rainfall. Issued by the Meteorological Office, this “regular annual publication” was devoted to the study of the “distribution of rain in space and time over the British Isles.” The Meteorological Office—imagine musty chambers in which masses of data are sorted and shuffled in search of a governing rule, a perfect patterne—was the successor to the still more august-sounding British Rainfall Organization.

Where most it promises.

—William Shakespeare, All’s Well that Ends Well (Act II, Scene I)

Established in 1858 by George James Symons, an exemplar of the Victorian obsession with statistics, the British Rainfall Organization made the British Isles a realm of watchful, patchily distributed observers. What was the weather like, say, on 1 December 1860, the date Charles Dickens—who all but invented London’s fog—published the first installment of Great Expectations in All the Year Round: A Weekly Journal? (In London: barometric pressure 29.66", temperature 45˚, wind from the east, overcast. That is, about what you would expect.) Rain and Rainfall—Great Britain—Periodicity—Periodicals. What kind of subject is this, so tightly corseted by inflexible hyphens? Does it yield to the smoothing and curve-fitting techniques of the mathematician? Or is it an irregular conjunction of things, somehow fixed in time, the meaning and sense of which only the poet can hope to scan? That it answers to neither and both of these descriptions will be shown in the following attempt to coax from it, however improbably, a thesis on history.

Our focus will be upon a group of mid-1920s papers, culled from journals on meteorology, statistics, and geography, whose authors were testing new methods for spotting undetected periodicities in time-series (sequences of observational data). Thus we will be on a “muddy road,” retracing the steps of these seekers of order—or of the screwily ordinal nature of data—as they plotted what all signs had led to them believe was the sinusoidal shape of time. The question such inquiry poses is whether there is a (straight, curving, zigzag, broken, continuous) plot to history and if so, how it should be limned. The reasoning runs as follows: in the recorded history of rainfall, made up of countless particulars which seem not so much to depart from as never care to approach the general reason of things, is written the prospect of a future regularity. This tenuous connection, between the once was and the not yet, breaks down not only of its own accord; it is uninterruptedly available to external disturbance. Model that disturbance and win the day, and days past, and days to come.

What we shall consider is a once seemingly possible merger between the Meteorological Office and that of the historian. Records were their common stock in trade. Time, order, and causation were the stuff of their shared meditation on before and after, on the consecution of tenses. Where the historians and meteorologists failed to come to terms was with what appeared likely in the unapprehended relations of things. Confronted with a tumultuous mass of facts, the historian loses sight of the presumable shape of time; the meteorologist finds in it a latent pattern. In his essay “Hypercritica, Or A Rule of Judgment For Writing or Reading Our Histories” (ca. 1618), Edmund Bolton writes, regarding varied opinions about how Britain came to be named Britain, “[I]f anything be clear in such a Case, or vehemently probable, it is both enough, and all which the Dignity of an Historian’s office doth permit.” Could students of the constitutively inconstant weather ask for any greater degree of certainty? It seems so. They heard secret harmonies, periodic rhythms repeated years on end.

A final preliminary word about periodicals. They appear weekly, fortnightly, quarterly, or at some other nominally regular interval. Except when they fail to do so. Particularly with laboriously tabulated meteorological data, the attempt to keep up with the present often proves the source of delay. Symons placed the blame for the chronically late appearance of British Rainfall on the negligence of his correspondents and on the time needed to correct errors in the records they eventually submitted. Better late than never. “Gave up hope of more,” reads the note appended to the catalogue entry for the Supplement to British Rainfall (1961–1965). A break in communication, a dry spell, a printers’ strike, the inexhaustible logic of the supplement? How do we read this desperate note? Was the cataloguer’s darkening hope that this regular annual publication would complete its run, the distribution of rain in space and time ever tending to norm? Or was it that the regular annual publication would merely resume, if only for appearance’s sake? Certainly there is always rain on the way. But what proves more difficult and correspondingly more rewarding to bring into line, editorially and otherwise, is that which is most subject to precipitate change: the past. Correction: make that history.

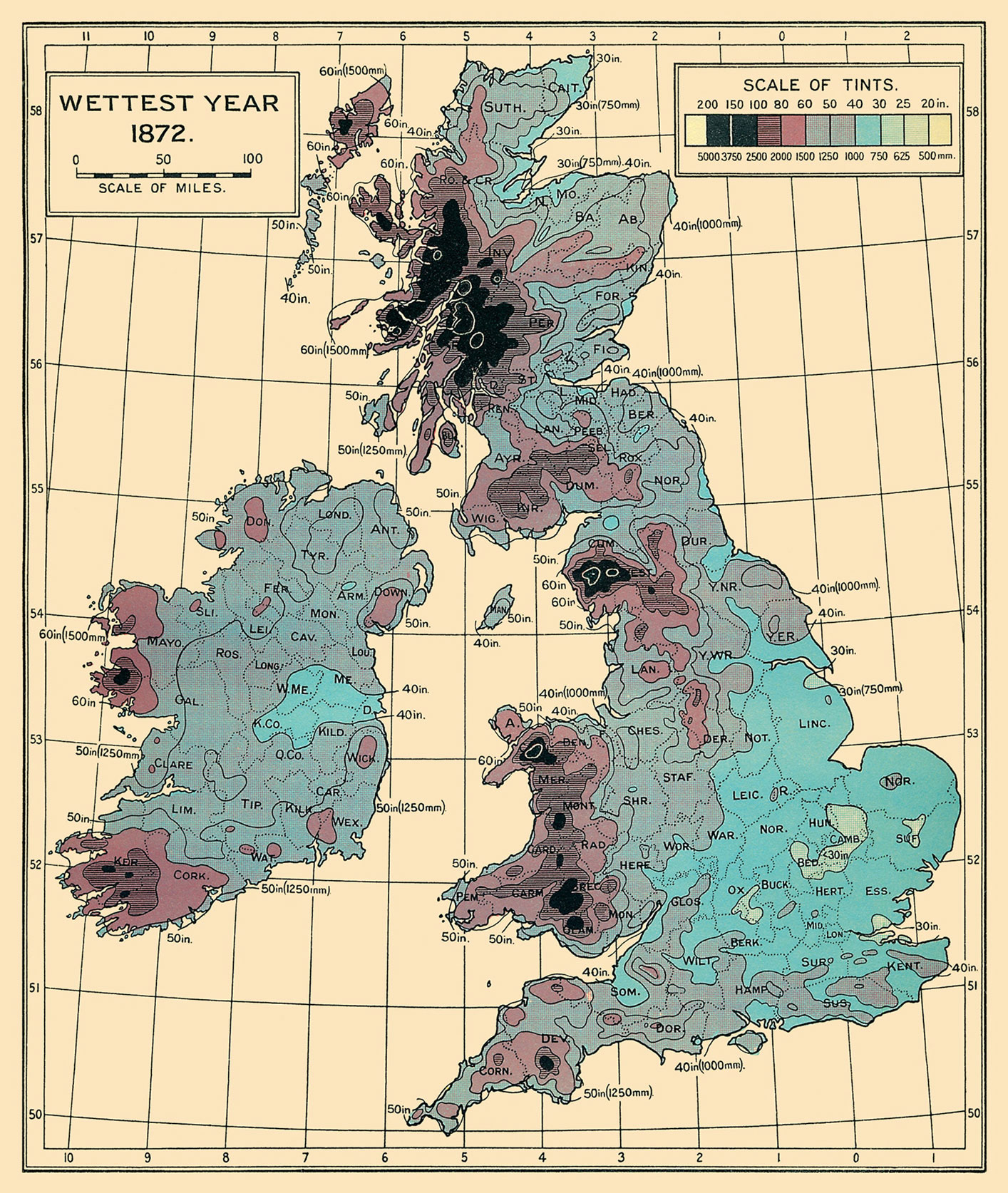

Illustration from the 1926 edition of Rainfall Atlas of the British

Isles, published by the Royal Meteorological Society of Great Britain.

The relevant clue to the method of history’s productive unmaking, indeed the very model of a purposefully “roving and unsettled” discourse, is to be found in Thomas Sprat’s The History of the Royal-Society of London (1667), where also may be consulted Robert Hooke’s synoptical “Method For Making a History of the Weather.” We refer specifically to Sprat’s description of the Fellows’ manner of compiling their Registers, so that they might be “nakedly transmitted to the next Generation of Men; and so from them to their Successors … without digesting them into any perfect model: so to this end, they confin’d themselves to no order of subjects; and whatever they have recorded, they have done it, not as compleat Schemes of opinions, but as bare unfinish’d Histories.”1....MUCH, so much, MORE

Evidently to learn from the past is as much a matter of saving its lessons from as saving them for an uncertain posterity. In this garden of the text, the nakedness of history is a manufactured state of grace, the better to weather the storms of time....