NYPD Sued For Secrecy Over Facial Recognition SystemApparently when asked if they were spies the police responded "We are not at liberty to discuss that."

Hmmm

And here is the second half of the headline at Citylab, April 24:

How to Disappear

Is it possible to move through a smart city undetected?

Even in the middle of major city, it’s possible to go off the grid. Last year, the Atlantic profiled a family in Washington, D.C., that harvests their entire household energy from a single, 1-kilowatt solar panel on a patch of cement in their backyard. Insulated, light-blocking blinds keep upstairs bedrooms cool at the peak of summer; in winter, the family gets by with low-tech solutions, like curling up with hot water bottles. “It’s a bit like camping,” one family member said.

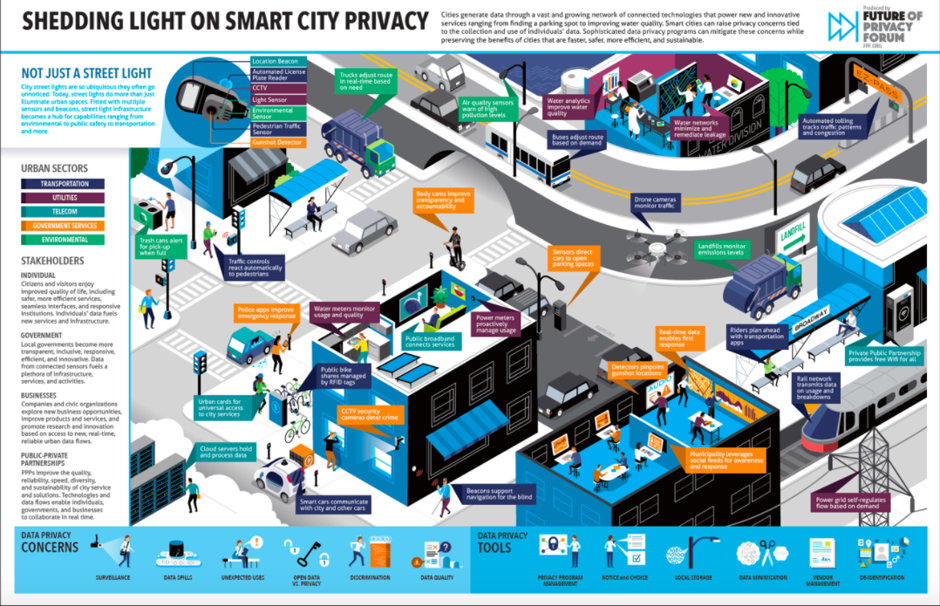

If extricating yourself from the electrical grid is, to some degree, a test of moxie and patience, extracting yourself from the web of urban surveillance technology strains the limits of both. If you live in a dense urban environment, you are being watched, in all kinds of ways. A graphic released last month by the Future of Privacy Forum highlights just how many sensors, CCTCV cameras, RFID readers, and other nodes of observation might be eying you as you maneuver around a city’s blocks. As cities race to fit themselves with smart technologies, it’s nearly impossible to know precisely how much data they’re accumulating, how it’s being stored, or what they’ll do with it.

“By and large, right now, it’s the Wild West, and the sheriff is also the bad guy, or could be,” says Albert Gidari, the director of privacy at Stanford Law School’s Center for Internet and Society.

Smart technologies can ease traffic, carve out safer pedestrian passages, and analyze environmental factors such as water quality and air pollution. But, as my colleague Linda Poon points out, their adoption is also stirring up a legal maelstrom. Surveillance fears have been aroused in Oakland, California,Seattle, and Chicago, and the applications of laws protecting citizen privacy are murky. For instance: data that’s stored on a server indefinitely could potentially infringe on the “right to be forgotten” that’s protected in some European countries. But accountability and recourse can be slippery, because civilians can’t necessarily sue cities for violating privacy torts, explains Gidari.

What would it look like to leapfrog that murkiness by opting out entirely? Can a contemporary urbanite successfully skirt surveillance? I asked Gidari and Lee Tien, a senior staff attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, to teach me how to disappear.

During the course of our conversations, Tien and Gidari each remind me, again and again, that this was a fool’s errand: You can’t truly hide from urban surveillance. In an email before our phone call, Tien points out that we’re not even aware of all the traces of ourselves that are out in the world. He likens our data trail—from parking meters, streetlight cameras, automatic license plate readers, and more—to a kind of binary DNA that we’re constantly sloughing. Trying to scrub these streams of data would be impossible.

Moreover, as the tools of surveillance have become more sophisticated, detecting them has become a harder task. “There was a time when you could spot cameras,” Tien says. Maybe a bodega would hang up a metal sign warning passersby that they were being recorded by a clunky, conspicuous device. “But now, they’re smaller, recessed, and don’t look like what you expect them to look like.”

Other cameras are in the sky. As Buzzfeed reported last spring, some federal surveillance technologies are mounted in sound-dampened planes and helicopters that cruise over cities, using augmented reality to overlay a grid that identifies targets at a granular level. “There are sensors everywhere,” Gidari says. “The public has no ability to even see where they are.”...MORE