From the Booth School of Business' ProMarket blog, April 6:

Is investigative journalism a private or public good? A new Stigler

Center case study focuses on the success of French online news website

Mediapart and explores the economics of media companies in the age of

digital disruption

Once a favorite to win France’s upcoming presidential election, François Fillon’s hopes of ever becoming president have been irrevocably dashed

in the past two months, following a series of revelations that as a

senator he had allegedly used public money originally intended for

paying assistants to pay hundreds of thousands of euros to his wife and

children for fake jobs as parliamentary aides. Previously the frontrunner, Fillon is now placed third in the polls, after he and his wife were formally charged with several counts of embezzlement and misappropriating public funds.

Many of the revelations that led to these

investigations and the derailment of Fillon’s campaign first appeared

in the online investigative magazine Mediapart. Back in 2014, Mediapart reported that at least 20 percent

of French parliament members employed their immediate family members

(hiring family members is legal for MPs in France, so long as the jobs

aren’t fake), calculating that 52 wives and 60 sons and daughters were

paid by MPs.

The Fillon scandal was the latest in a long string of investigations by Mediapart, a hard-hitting investigative website launched in 2008 by Edwy Plenel, the former editor-in-chief of the French newspaper Le Monde. In the past 9 years, on the back of several high-profile investigations that shook French politics and business world, Mediapart

has become one of France’s leading news outlets, with a growing

subscriber base that rivals those of some of the country’s major legacy

newspapers.

Moreover, Mediapart has also

managed to become highly profitable—practically unheard-of for an online

investigative news outlet—despite the fact that its business model

overtly defies every truism about how media outlets should operate in

the digital world: it displays no ads, has no corporate backers, and its

only source of revenue are the monthly fees paid by its subscribers.

Nevertheless, it still pays its journalists competitive salaries.

Mediapart is the subject of the first in a series of case studies

by the Stigler Center at the University of Chicago Booth School of

Business. It was chosen because of the crucial role independent

investigative journalism plays in reducing the power of vested interests

and allowing for competitive markets to function properly. The case was

written by Dov Alfon, Haaretz‘s editor-at-large in Paris, with

a teaching note written by Guy Rolnik, a Clinical Associate Professor

at Chicago Booth and Co-Director of the Stigler Center [also, one of the

editors of this blog]. On April 13, the case will be presented in a special Stigler Center event that

will feature Plenel, his co-founder Marie-Hélène Smiejan-Wanneroy, and

James T. Hamilton, the Hearst Professor of Communication and the

Director of the Journalism Program at Stanford.

In a global media landscape that’s characterized by shrinking ad revenues, conventional wisdom has it that investigative journalism is financially unviable. In his recent book Democracy’s Detectives,

which examines the economics of investigative journalism, Hamilton

writes: “Investigative reporting involves original work, about

substantive issues, that someone wants to keep secret. It is costly,

underprovided in the marketplace, and often opposed. It is more likely

done when a media outlet has the resources to cover the costs, an

incentive to tell a new story, cares about impacts, and overcomes

obstacles. Changes in media markets put local investigative reporting at

risk.”

With the disintegration

of journalism’s business model, newspapers were left with fewer

resources to fund costly and time-consuming investigations into the

misdeeds of politicians and regulators. Since the nature of the web

makes it more difficult to exclude access to information, and therefore

charge for it, private firms have far fewer incentives to produce it.

These developments, scholars like Hamilton say, have made investigative

journalism more of a public good.

Can we really expect the market to supply

quality investigative journalism that exposes wrongdoing, uncovers

corruption, and holds the powerful to account? Many would say there’s

simply no demand for it. The success of Mediapart, however, may provide a unique counterfactual.

Plenel, the publisher, editor-in-chief, and leading force behind Mediapart,

established the site in late 2007 together with three other partners,

all veteran journalists—Laurent Mauduit, François Bonnet, and Gérard

Desportes—with the aim of providing a new outlet for investigative

journalism that would not be beholden to any political or financial

interests. The four were all highly experienced journalists, but had

absolutely no experience in business. For this, they relied on

Smiejan-Wanneroy, an entrepreneur and marketing expert. They managed to

raise €2.9 million prior to launching, mostly from friends, two

individual investors, and out of their own pockets, figuring that 50,000

subscribers would allow them to break even.

In order to achieve total independence, Mediapart’s

founders chose a unique business model, which includes no advertising

and instead relies on subscription fees to pay for content—a risky proposition

today and even riskier in 2007, back when most news outlets had yet to

erect paywalls and the notion that readers would never be willing to pay

for online content was the predominant view.

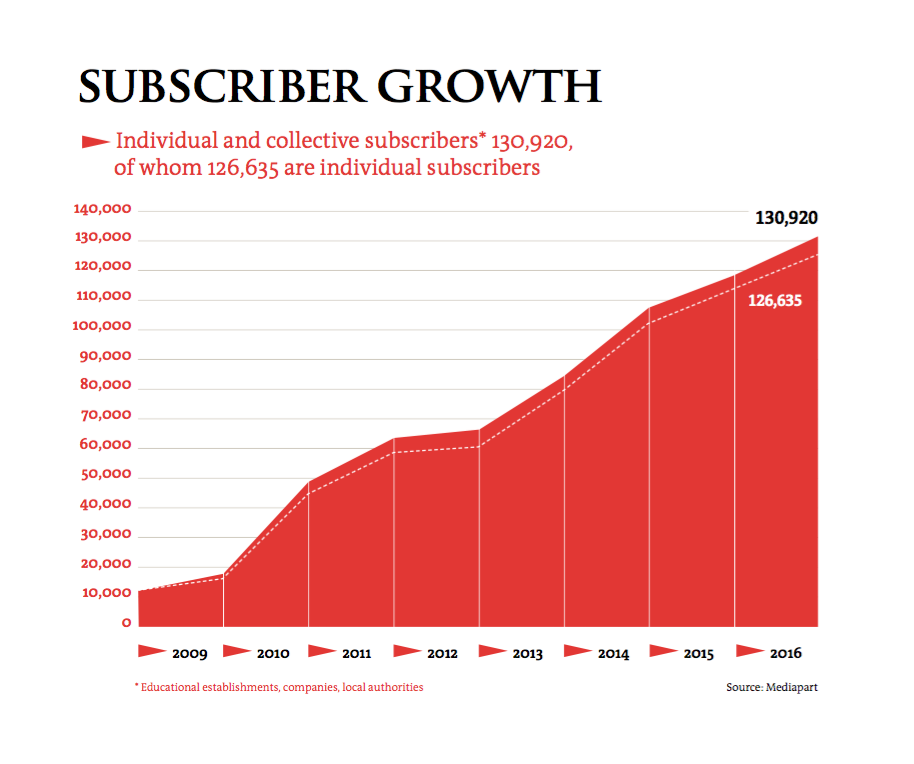

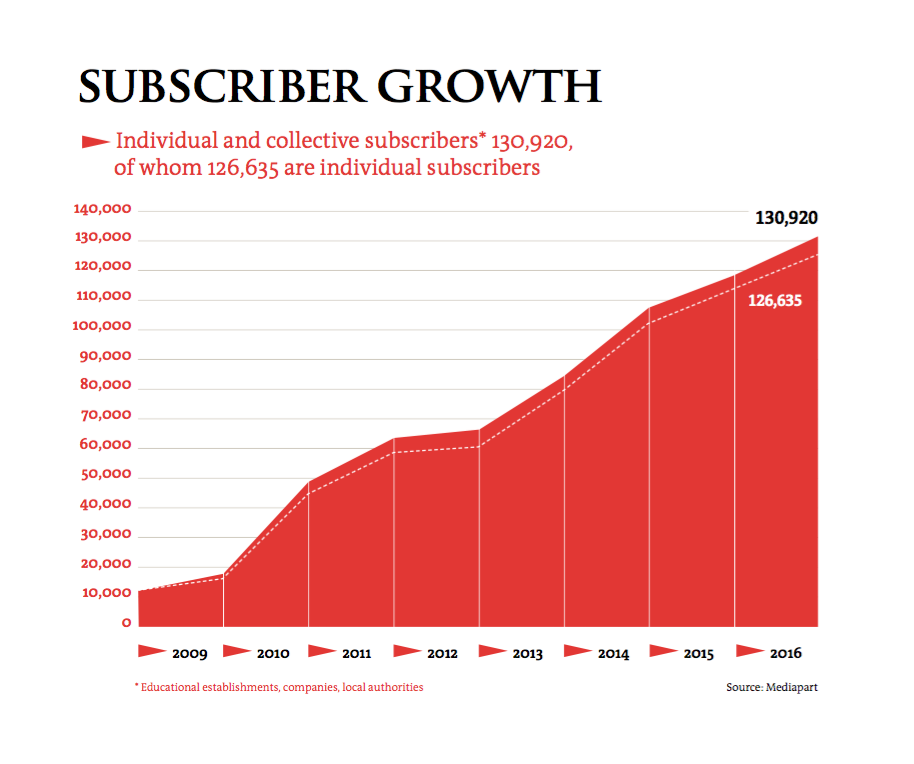

Despite having no source of revenue other

than its monthly subscription fee (currently at €11 and initially €9,

although various promotional deals have offered reduced fees), Mediapart has been profitable since 2011—three years after its launch. For 2016, it reported a net profit

of €1.9 million and a 10 percent growth in revenues. It currently has

140,000 subscribers (compared with 15,000 in 2010), and its subscription

revenues have grown more than 18-fold since 2008.

Mediapart’s profitability stands out, even when compared to much older, much bigger, much more established counterparts: Mediapart’s operating margin was 18 percent in 2016, compared with 6.5 percent for the New York Times. Similarly, while the Times’ net margin stood at 1.9 percent last year, Mediapart had a net margin of 16.6 percent....MORE