“Every season since the Gold Rush, California has blossomed with new money — first in gold, then in land, cattle, railroads, agriculture, film images, shipbuilding, aerospace, electronics, television and commercial religions. The ease with which the happy few become suddenly rich lends credence to the belief in magical transformation.”

— Lewis Lapham, 1979, “Lost Horizon”

“When do you think people in the Bay Area started to realize that you could make more money from tech than from real estate?” Jed Kolko asked me.

We were sitting at Ma-velous, a coffee shop frequented by San Francisco’s political movers two blocks from City Hall and kitty corner from Twitter’s headquarters in the Shorenstein-owned former San Francisco Furniture Mart.

Just outside the window was Market Street, San Francisco’s main thoroughfare. In 1847, two years before the Gold Rush transformed the city into a teeming boomtown, a 30-year-old Irish immigrant named Jasper O’Farrell presciently surveyed the street to be 120 feet wide — which is broader than the Philadelphia main street it was named after — even though the city was only 500 residents strong at the time.

“1980s,” I said in response to his question. Seemed obvious. The PC revolution. Steve Jobs and Apple. And a decade after the Peninsula was christened “Silicon Valley” by an electronics trade newsletter and the “Fairchildren,” or alumni of Fairchild Semiconductor, went on to found Intel, National Semiconductor and AMD.

2005 was his guess. The year after Google IPO-ed, and when escalating home prices made real estate an ever-riskier bet. That was the year that he felt that more people started coming to San Francisco for professional ambition rather than lifestyle reasons such as being openly gay or for pursuing callings that didn’t need to be so well-compensated.

Like a handful of other people at the intersection of real estate and technology, Kolko would be in a position to make an educated stab. He led some research at the well-regarded nonprofit, non-partisan think tank Public Policy Institute of California for five years, and then was the head economist at real estate startup Trulia.

It was a provocative rhetorical question. Land, labor, capital. Technological change. How do they intersect?

Cities, or physical communities, are one of the hardest kinds of scaling problems that exist.

In some ways, we’re lucky that the first two decades involving the advent of the commercial Internet were largely a positive-sum game. The creation of digital space for self-expression, at near-zero cost, does not necessarily challenge or erode someone else’s right to space or resources.

That makes it easy to forget that California is a state built throughout generations of conflict over land and its inherent constraints. It is this oldest of resources — not capital or human talent or ingenuity — that most constrains the region’s potential for workers at all income levels.

Cities, or physical communities, are one of the hardest kinds of scaling problems that exist. The infrastructure needed to sustain bigger networks, such as schools, sewers and mass transit, gets harder — not easier — to develop, finance and maintain the larger your population becomes.

There are countless constituencies of different incomes, racial groups, interests and professions that are all vying with each other for limited space. Although it’s possible to build up, urban development is much more of a zero-sum game.

With every major economic shift , from an agrarian to an industrial economy, and then an industrial to a knowledge-and-services economy , California and the United States have faced distinctive junctures in their approach to land-use and housing.

California’s fragmented, post-war suburban model, which was created for a more even wage distribution in a mass industrial economy, is clearly becoming more dysfunctional by the year.

I believe we’re hitting another major juncture, although I don’t know when it will deteriorate to the point that it forces real reform. California’s fragmented, post-war suburban model, which was created for a more even wage distribution in a mass industrial economy, is clearly becoming more dysfunctional by the year for a knowledge-and-services economy with a wider level of income stratification.

Not only are we not building enough housing overall, we have scarce sources of funding for supporting those on the lower-earning ends of a rapidly widening income spectrum. So we end up politicizing and extracting funds out of new construction even though we are 40 years deep into a largely self-imposed housing shortage.

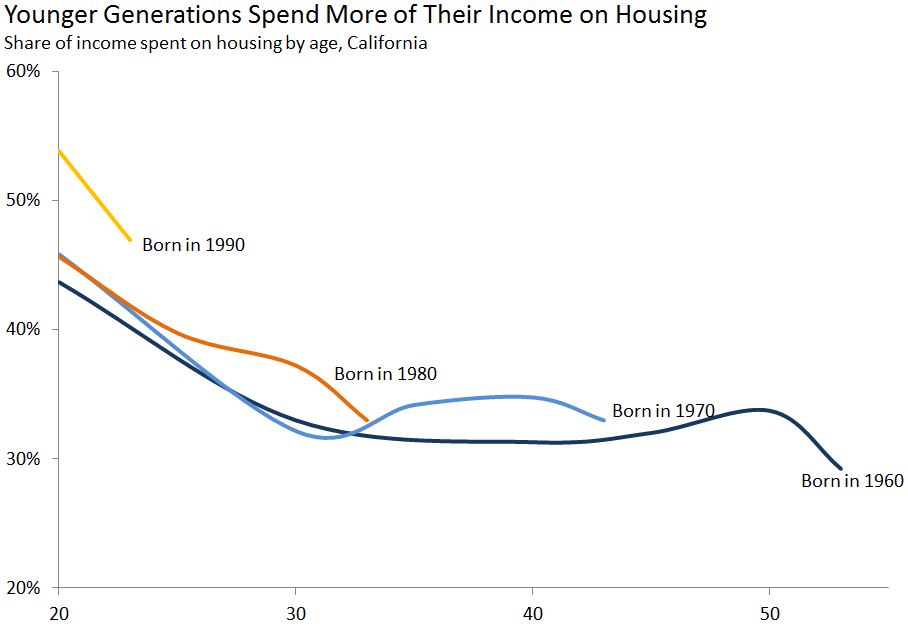

There are a couple of disturbing trends showing up in the data. If you look across the state’s workforce, Californians born in 1990 are on average spending 50 percent of their income on housing. That’s way above the 30-percent-of-income level that is generally considered to be the threshold of whether housing is affordable or not in public policy conversations.

Then, if you look at working-class segments, commutes are rapidly rising for the lower-income workers in the region:

This is troubling because commute time is one of the strongest predictive factors in determining a child’s chances of climbing from the lowest income quintile to the highest-earning one. That morning and evening time between parents and children that is taken up by commuting is invaluable for bonding and child development.

Cities around the Bay Area are starting to contort themselves into stranger and stranger positions just to support basic public services.

Suburbs like Cupertino, where Apple is headquartered, are now having to build teacher public housing projects for tens of millions of dollars because the cost of living is too high for an entry-level teacher making $55,000 a year.Previously:

Meanwhile, the city has approved another Apple campus that will bring 13,000 additional Apple employees to the city, while only committing to building 1,400 housing units over the next seven years.

I’m not sure when a breaking point happens, but I want to offer some essays and short pieces over the next few days to give you a couple of takeaways. The TL;DR is that I’m going to start working on new projects soon, but I want to leave a map behind of what I think has to be done long-term in Northern California.

An old problem

California has faced housing and land shortages multiple times and has changed its regulatory regimes in response. I’m going to start with two histories from the state’s first Gilded Age and post-war era.

In the first Gilded Age, the concern was over land monopolization by a handful of large-scale owners and how that crowded out and impoverished labor. In the postwar period, California leveraged the automobile and federal subsidies to unlock previously inaccessible land and create a golden age of cheap housing and suburbanization.

This boom period ended in the 1970s as the state’s flat, developable coastal lands were built out and the oil crisis made sprawl more expensive. That’s when housing shifted from being perceived as a consumable good to an investable asset.

Since then, a new generational land cartel has emerged with Californian Baby Boomers protecting entitlements and higher property values for themselves in the form of land-use restrictions and Proposition 13. Global capital has been subverting and taking advantage of these favorable legal and taxation protections on real estate in a extremely low interest-rate world. All of this has come at the cost of the state’s working and middle class and its future workforce.

It’s a global issue

It faces major cities in all economies that chose a housing-as-an-investable-asset model following World War II like the U.K. and Australia....MORE

Forgetting History: "Nothing Like This Has Ever Happened Before"