Venezuela will be defaulting in 2015. The odds are around 50/50 that Nigeria will descend into a civil war.

That is if you don't consider kidnapping schoolgirls and making them sex slaves is already civil war.

And if these prices last much more than than a couple years the rulers of Saudi Arabia will probably be moving to Switzerland as there are some very hard core religious types who would be taking control of the country and its oil.

From Gavyn Davies at the Financial Times:

The dark side of the oil shock

The financial markets saw only bad news in the oil shock last week. Despite extremely strong US consumer data, there is a reluctance to recognise the shock for what it is – a long-lasting structural change, with mostly beneficial consequences for aggregate demand in the developed economies.HT: FT Alphaville "The oddly subdued optimism about falling oil prices"

As John Authers explains, weak Chinese data are causing concern, but there is little evidence that China has been the main cause of falling oil prices. Global oil demand has been fairly stable as supply has surged, and it is surely revealing that the latest oil price drop followed the Saudi decision to maintain oil output after the November OPEC meeting.

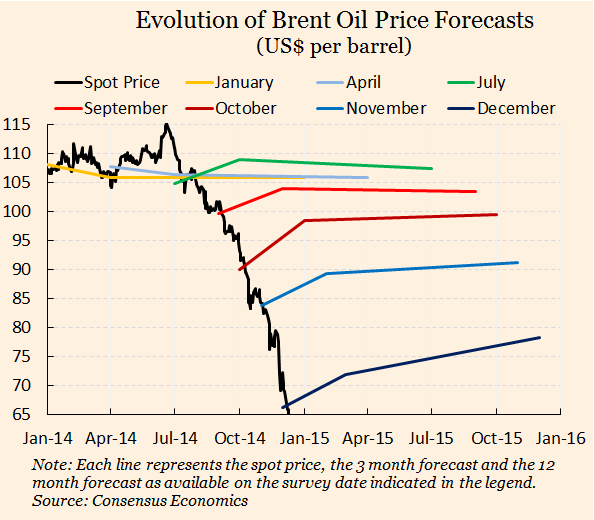

Like investors, economists have been thrown into confusion. Almost no-one in the profession (including myself) predicted the oil price collapse in advance. After the shock, it took months for oil price forecasts to be brought into line with the new reality. Futures prices in the oil market have performed no better: predicting oil prices can be a mug’s game.

More surprisingly, there has also been a disinclination to accept the potential benefits in the oil shock. Some economists have said it largely reflects an adverse demand shock in the global economy, so it is axiomatically bad news. Others have said that, even if it is a supply shock in the oil market, which would normally be beneficial, this time will be different, because it will be deflationary, and will therefore raise real interest rates.

There are some honourable exceptions, like Martin Wolf and David Wessel who have viewed it mainly as a supply shock with net beneficial consequences. But the pessimists have thrown up a lot of noise, reminding me of Professor Deirdre McCloskey’s maxim:

Pessimism sells. For reasons I have never understood, people like to hear that the world is going to hell, and become huffy and scornful when some idiotic optimist intrudes on their pleasure.If the pessimists have a case, it is in oil producers in the emerging world, especially Russia. But, among oil importers in the developed world, it is hard to see too much of a dark side.

Let’s start with what Basil Fawlty would call “the bleeding obvious”. A fall in oil prices redistributes income away from oil producers, of whom there are relatively few, towards oil consumers, of whom there are very many. To a first approximation, the long run effect of this income transfer on the global economy should be small, but beneficial. The beneficial part comes from permanently lower production costs, which allow central banks to target lower unemployment rates while still hitting their inflation targets. This is a long run supply-side gain that is the direct opposite of the stagflation that occurred in the 1970s....MORE