A magnetogram recorded at the Greenwich Observatory in London during the Carrington Event of 1859.

Noon approached on September 1, 1859, and British astronomer Richard Christopher Carrington

was busy with his favorite pastime: tracking sunspots, those huge

regions of the star darkened by shifts in its magnetic field. He

projected the Sun's image from his viewing device onto a plate of glass

stained a "pale straw colour," which gave him a picture of the fiery

globe one inch shy of a foot in diameter.

The morning's work went as normal. Carrington patiently counted and charted spots, time-lining changes in their positions with a chronometer. Then he saw something unusual.

"Two patches of intensely bright and white light broke out," he later wrote.

Carrington puzzled over the flashes. "My first impression was that by

some chance a ray of light had penetrated a hole in the screen attached

to the object-glass," he explained, given that "the brilliancy was fully

equal to that of direct sun-light."

"Two patches of intensely bright and white light broke out," he later wrote.

Carrington puzzled over the flashes. "My first impression was that by

some chance a ray of light had penetrated a hole in the screen attached

to the object-glass," he explained, given that "the brilliancy was fully

equal to that of direct sun-light."

The astronomer checked his gear. He moved the apparatus around a bit. To his surprise, the intense white patches stayed put. Realizing that he was an "unprepared witness of a very different affair," Carrington ran out of his studios to find a second observer. But when he brought this person back, he was "mortified to find" that the bright sections were "already much changed and enfeebled."

"Very shortly afterwards the last trace was gone," Carrington wrote. He kept watch on the region for another hour, but saw nothing more. Meanwhile, the explosive energy that he had seen rushed towards him and everyone else on earth.

Better than batteries

It hit quickly. Twelve hours after Carrington's discovery and a continent away, "We were high up on the Rocky Mountains sleeping in the open air," wrote a correspondent to the Rocky Mountain News. "A little after midnight we were awakened by the auroral light, so bright that one could easily read common print." As the sky brightened further, some of the party began making breakfast on the mistaken assumption that dawn had arrived.

Across the United States and Europe, telegraph operators struggled to keep service going as the electromagnetic gusts enveloped the globe. In 1859, the US telegraph system was about 20 years old, and Cyrus Field had just built his transatlantic cable from Newfoundland to Ireland, which would not succeed in transmitting messages until after the American Civil War.

"Never in my experience of fifteen years in working telegraph lines have I witnessed anything like the extraordinary effect of the Aurora Borealis between Quebec and Farther Point last night," wrote one telegraph manager to the Rochester Union & Advertiser on August 30:

The morning's work went as normal. Carrington patiently counted and charted spots, time-lining changes in their positions with a chronometer. Then he saw something unusual.

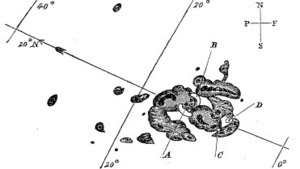

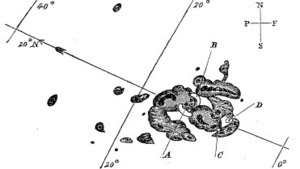

Richard

Carrington's 1859 drawing of the solar flares he identified while

sunspot watching. The "intensely bright" patches are marked A and B.

The astronomer checked his gear. He moved the apparatus around a bit. To his surprise, the intense white patches stayed put. Realizing that he was an "unprepared witness of a very different affair," Carrington ran out of his studios to find a second observer. But when he brought this person back, he was "mortified to find" that the bright sections were "already much changed and enfeebled."

"Very shortly afterwards the last trace was gone," Carrington wrote. He kept watch on the region for another hour, but saw nothing more. Meanwhile, the explosive energy that he had seen rushed towards him and everyone else on earth.

Better than batteries

It hit quickly. Twelve hours after Carrington's discovery and a continent away, "We were high up on the Rocky Mountains sleeping in the open air," wrote a correspondent to the Rocky Mountain News. "A little after midnight we were awakened by the auroral light, so bright that one could easily read common print." As the sky brightened further, some of the party began making breakfast on the mistaken assumption that dawn had arrived.

Across the United States and Europe, telegraph operators struggled to keep service going as the electromagnetic gusts enveloped the globe. In 1859, the US telegraph system was about 20 years old, and Cyrus Field had just built his transatlantic cable from Newfoundland to Ireland, which would not succeed in transmitting messages until after the American Civil War.

"Never in my experience of fifteen years in working telegraph lines have I witnessed anything like the extraordinary effect of the Aurora Borealis between Quebec and Farther Point last night," wrote one telegraph manager to the Rochester Union & Advertiser on August 30:

The line was in most perfect order, and well skilled operators worked incessantly from 8 o'clock last evening till one this morning to get over in an intelligible form four hundred words of the report per steamer Indian for the Associated Press, and at the latter hour so completely were the wires under the influence of the Aurora Borealis that it was found utterly impossible to communicate between the telegraph stations, and the line had to be closed....MUCH MORE

Frederic

Edwin Church's 1865 painting "Aurora Borealis." Some speculate that

Church took his inspiration from the Great Auroral Storm of 1859.