From SemiAnalysis, February 9:

RL and Agent Usage, Context Memory Storage, DRAM Pricing Impacts, CPU Interconnect Evolution, AMD Venice, Verano, Florence, Intel Diamond Rapids, Coral Rapids, Arm Phoenix + Venom, Graviton 5, Axion

Since 2023, the datacenter story has been simple. GPUs and networking are king. The arrival and subsequent explosion of AI Training and Inference have shifted compute demands away from the CPU. This meant that Intel, the primary supplier of server CPUs, failed to ride the wave of datacenter buildout and spending. Server CPU revenue remained relatively stagnant as hyperscalers and neoclouds focused on GPUs and datacenter infrastructure.

At the same time, the same hyperscalers have been rolling their own ARM-based datacenter CPUs for their cloud computing services, closing off a significant addressable market for Intel. And within their own x86 turf, Intel’s lackluster execution and uncompetitive performance to rival AMD has further eroded market share. Without a competent AI accelerator offering, Intel was left to tread water while the rest of the industry feasted.

Over the last 6 months this has changed massively. We have posted multiple reports to Core Research and the Tokenomics Model about soaring CPU demand. The primary drivers we have shown and modeled are reinforcement learning and vibe coding’s incredible demand on CPUs. We have also covered major CPU cloud deals by multiple vendors with AI labs. We also have modeling of how many CPUs of what types are being deployed.

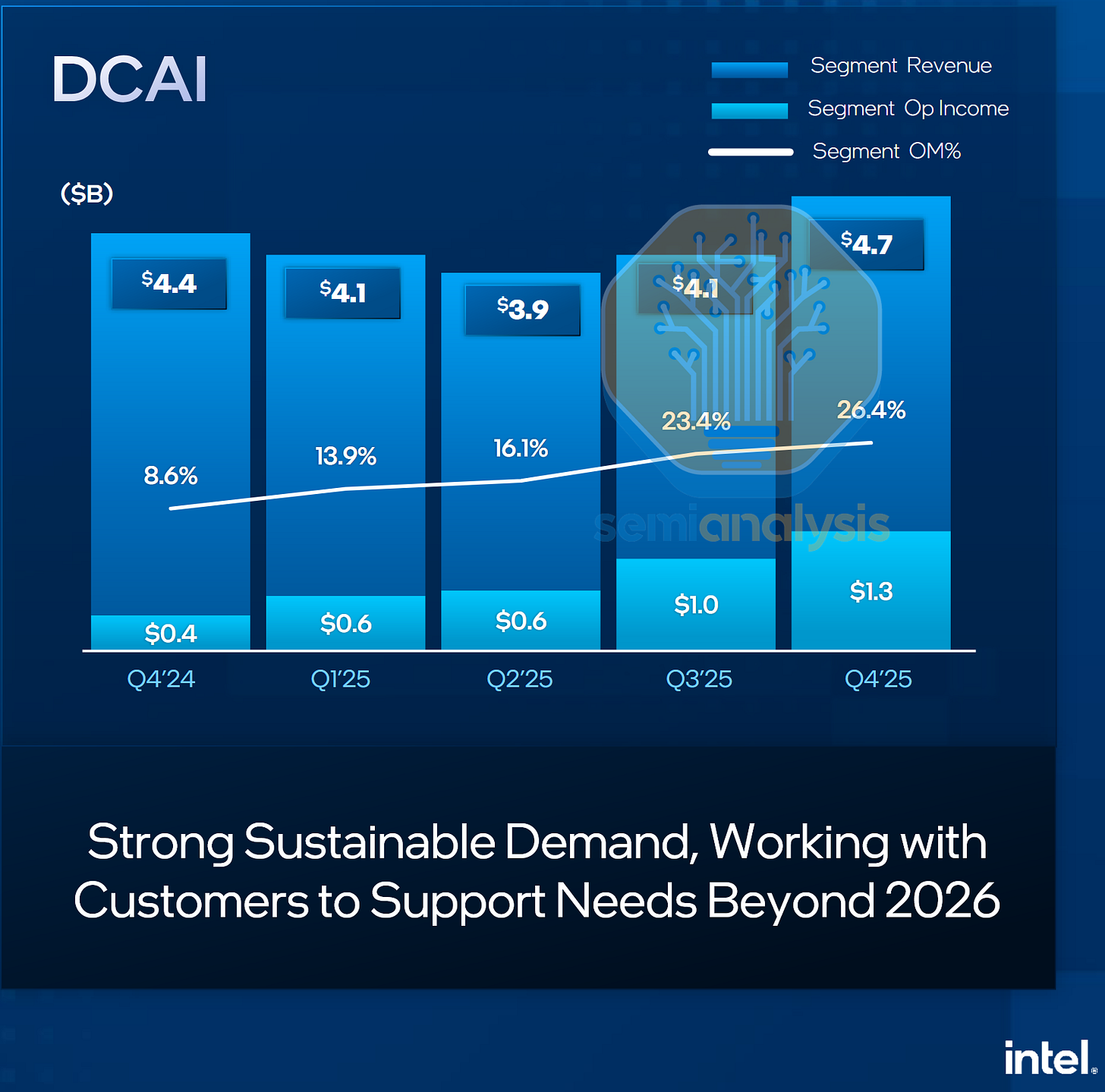

Intel Q4’25 DCAI Revenue. Source: Intel

However, Intel’s recent rallies and changing demand signals in the latter part of 2025 have shown that CPUs are now relevant again. In their latest Q4 earnings, Intel saw an unexpected uptick in datacenter CPU demand in late 2025 and are increasing 2026 capex guidance on foundry tools and prioritizing wafers to server from PC to alleviate supply constraints in serving this new demand. This marks an inflection point in the role of CPUs in the datacenter, with AI model training and inference using CPUs more intensively.

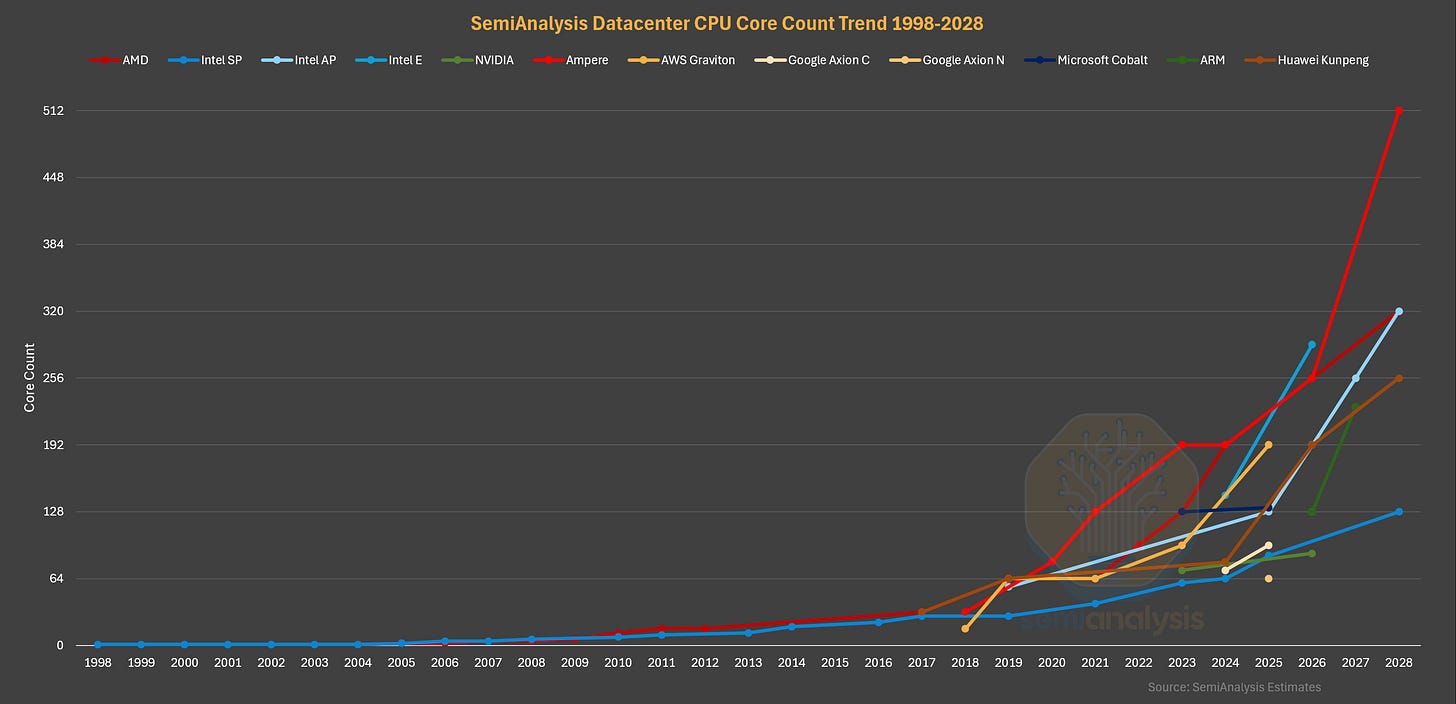

Datacenter CPU Core Count Trend. Source: SemiAnalysis Estimates

2026 is an exciting year for the datacenter CPU, with many new generations launching this year from all vendors amid the boom in demand. As such, this piece serves to paint the CPU landscape in 2026. We lay the groundwork, covering the history of the datacenter CPU and the evolving demand drivers, with deep dives on datacenter CPU architecture changes from Intel and AMD over the years.

We then focus on the 2026 CPUs, with comprehensive breakdowns on Intel’s Clearwater Forest, Diamond Rapids and AMD’s Venice and their interesting convergence (and divergence) in design, discussing the performance differences and previewing our CPU costing analysis.

Next, we detail the ARM competition, including NVIDIA’s Grace and Vera, Amazon’s Graviton line, Microsoft’s Cobalt, Google’s Axion CPU lines, Ampere Computing’s merchant ARM silicon bid and their acquisition by Softbank, ARM’s own Phoenix CPU design and look at Huawei’s home grown Kunpeng CPU efforts.

For our subscribers, we provide our datacenter CPU roadmap to 2028 and detail the datacenter CPUs beyond 2026 from AMD, Intel, ARM and Qualcomm. We then look ahead to what the future looks like for datacenter CPUs, discuss the effects of the DRAM shortage, what NVIDIA’s Bluefield-4 Context Memory Storage platform means for the future of general purpose CPUs, and the key trends to look out for in the CPU market and CPU designs going forward.

The Role and Evolution of Datacenter CPUs

The PC EraThe modern version of the datacenter CPU can be traced back to the 1990s following the success of Personal Computers in the prior decade, bringing basic computing into the home. As PC processing power grew with Intel’s i386, i486 and Pentium generations, many tasks normally computed by advanced workstation and mainframe computers from the likes of DEC and IBM were instead done on PCs at a fraction of the cost. Responding to this need for higher performance “mainframe replacements”, Intel began to release PC processor variants that had more performance and larger caches for higher prices, starting with the Pentium Pro in 1995 that had multiple L2 cache dies co-packaged with the CPU in a Multi-Chip Module (MCM). The Xeon brand then followed suit in 1998, with the Pentium II Xeons that similarly had multiple L2 cache dies added to the CPU processor slot. While mainframes still continue today in the IBM Z lines used for bank transaction verifications and such, they remain a niche corner of the market that we will not cover in this piece.

The Dot Com Era

The 2000s brought the internet age, with the emergence of Web 2.0, e-mail, e-commerce, Google search, smartphones with 3G broadband data, and the need for datacenter CPUs to serve the world’s internet traffic as everything went online. Datacenter CPUs grew into a multi-billion dollar segment. On the design front, after the GHz wars were over with the end of Dennard scaling, attention shifted to multi-core CPUs and increased integration. AMD integrated the memory controller into the CPU silicon, and high-speed IO (PCIe) came directly from the CPU as well. Multi-core CPUs were especially suited for datacenter workloads, where many tasks could be run in parallel across different cores.We will detail the evolution of how these multiple cores are connected in the interconnect section below. Simultaneous Multi-Threading (SMT) was also introduced in this time by both AMD and Intel, partitioning a core into two logical threads that could operate independently while sharing most core resources, further improving performance in parallelizable datacenter workloads. Those looking for more performance would turn to Multi-socket CPU servers, with Intel’s Quick Path Interconnect (QPI) and AMD’s HyperTransport Direct Connect Architecture in their Opteron CPUs providing coherent links between up to eight sockets per server.

The Virtualization and Cloud Computing Hyperscaler Era

The next major inflection point came with cloud computing in the late 2000s, and was the primary growth driver for datacenter CPU sales throughout the 2010s. Much like how GPU Neoclouds are operating today, computing resources began consolidating toward public cloud providers and hyperscalers such as Amazon’s Web Services (AWS) as customers traded CapEx for OpEx. Spurred by the effects of the Great Recession, many enterprises could not afford to buy and run their own servers to run their software and services.Cloud computing offered a far more palatable “pay as you use” business model with renting compute instances and running your workloads on 3rd-party hardware, which allowed spending to dynamically adjust with usage that varied over time. This scalability was more favorable than procuring one’s own servers, which needed to be utilized fully at all times to maximize ROI. The Cloud also enabled more streamlined services to emerge, such as serverless computing from the likes of AWS Lambda that automatically allocates software to computing resources, sparing the customer from having to decide on the appropriate number of instances to spin up before running a particular task. With nearly everything handled by them behind the scenes, Clouds turned compute into a commodity....

....MUCH MORE

However....

February 18 - "Why Nvidia’s deal with Meta is an ‘Intel killer,’ according to this analyst" (NVDA; META; ARM; INTC; AVGO)

February 20 - "Nvidia is moving in on Intel and AMD's home turf" (NVDA; INTC; AMD; META)

The market may not have fully absorbed this news when it crossed the tape a couple days ago.*