We too have flirted with models, and came away puzzled. Some links below.

From Works in Progress, July 21:

Behavioral economics has identified dozens of cognitive biases that stop us from acting ‘rationally’. But instead of building up a messier and messier picture of human behavior, we need a new model.

From the time of Aristotle through to the 1500s, the dominant model of the universe had the sun, planets, and stars orbiting around the Earth.

This simple model, however, did not match what could be seen in the skies. Venus appears in the evening or morning. It never crosses the night sky as we would expect if it were orbiting the Earth. Jupiter moves across the night sky but will abruptly turn around and go back the other way.

To deal with these ‘anomalies’, Greek astronomers developed a model with planets orbiting around two spheres. A large sphere called the deferent is centered on the Earth, providing the classic geocentric orbit. The smaller spheres, called epicycles, are centered on the rim of the larger sphere. The planets orbit those epicycles on the rim. This combination of two orbits allowed planets to shift back and forth across the sky.

But epicycles were still not enough to describe what could be observed. Earth needed to be offset from the center of the deferent to generate the uneven length of seasons. The deferent had to rotate at varying speeds to capture the observed planetary orbits. And so on. The result was a complicated pattern of deviations and fixes to this model of the sun, planets, and stars orbiting around the Earth.

Instead of this model of deviations and epicycles, what about an alternative model? What about a model where the Earth and the planets travel in elliptical orbits around the sun?

By adopting this new model of the solar system, a large collection of deviations was shaped into a coherent model. The retrograde movements of the planets were given a simple explanation. The act of prediction became easier as a model that otherwise allowed astronomers to muddle through became more closely linked to the reality it was trying to describe.

***

Behavioral economics today is famous for its increasingly large collection of deviations from rationality, or, as they are often called, ‘biases’. While useful in applied work, it is time to shift our focus from collecting deviations from a model of rationality that we know is not true. Rather, we need to develop new theories of human decision to progress behavioral economics as a science. We need heliocentrism.

The dominant model of human decision-making across many disciplines, including my own, economics, is the rational-actor model. People make decisions based on their preferences and the constraints that they face. Whether implicitly or explicitly, they typically have the computational power to calculate the best decision and the willpower to carry it out. It’s a fiction but a useful one.

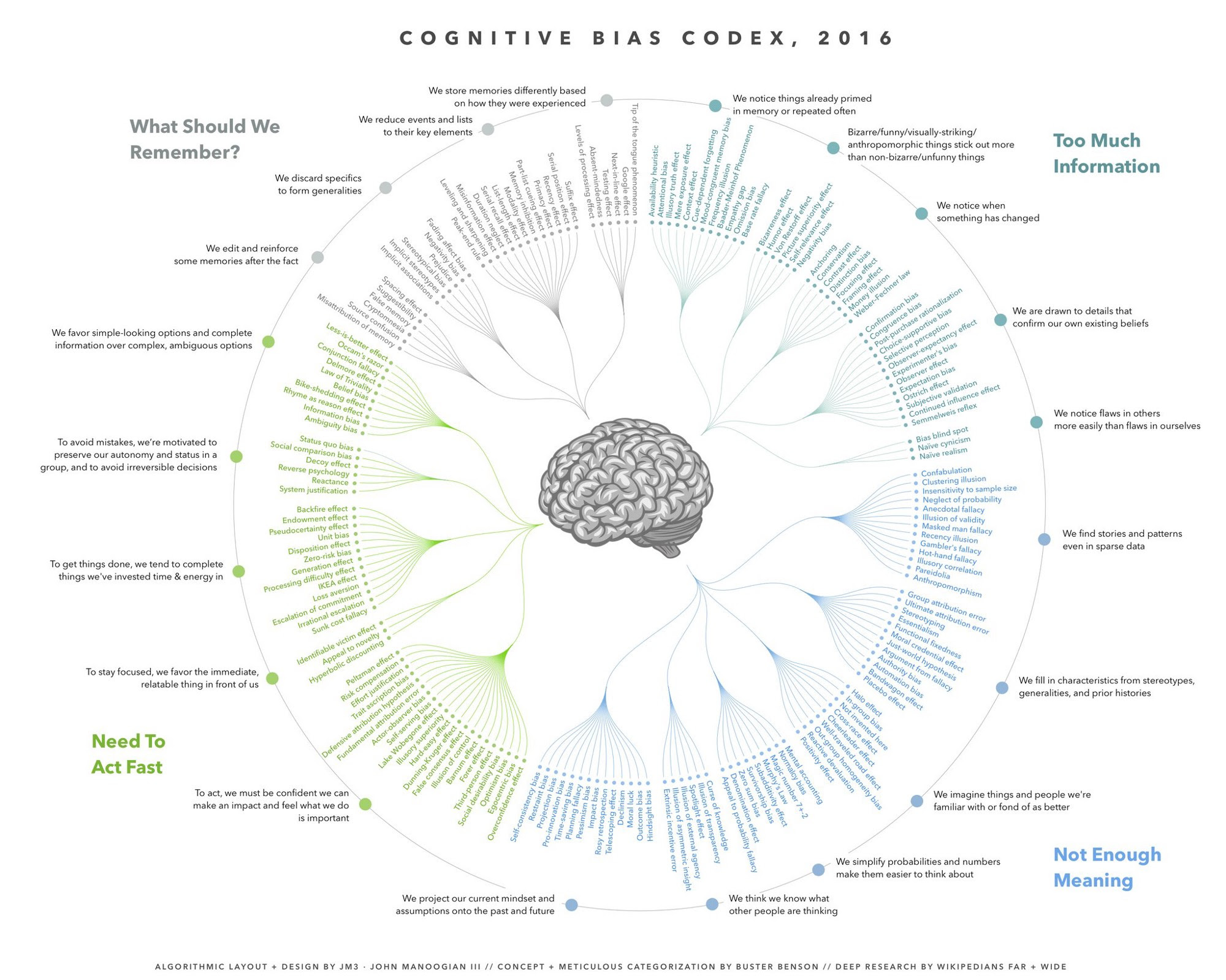

As has become broadly known through the growth of behavioral economics, there are many deviations from this model. (I am going to use the term behavioral economics through this article as a shorthand for the field that undoubtedly extends beyond economics to social psychology, behavioral science, and more.) This list of deviations has grown to the extent that if you visit the Wikipedia page ‘List of Cognitive Biases’ you will now see in excess of 200 biases and ‘effects’. These range from the classics described in the seminal papers of Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman through to the obscure.

We are still at the collection-of-deviations stage. There are not 200 human biases. There are 200 deviations from the wrong model.

Why we study biases

The collection of deviations in astronomy did have its uses. Absent the knowledge of heliocentric orbits, astronomers still made workable predictions of astronomical phenomena. Ptolemy’s treatise on the motions of the stars and planets, Almagest, was used for more than a millennium.The collection of biases also has practical applications. Today’s highest-profile behavioral economics stories and publications involve applied problems, be that boosting gym attendance, vaccination rates, organ donation, retirement savings, or tax return submission. Develop an intervention based on potential biases leading to the (often assumed) suboptimal behavior, test, and publish. This program of work has had some success.

But there is something unsatisfying about this being the frontier of behavioral economics as a science. Dig into many of these applications and you see a philosophy of ‘grab a bunch of ideas and see which ones work’. There is no theoretical framework to guide the selection of interventions, but rather a potpourri of empirical phenomena to pan through.

Selecting the right interventions is not trivial. Suppose you are studying a person deciding on their retirement savings plans. You want to help them make a better decision (assuming you can define it). So which biases could lead them to err? Will they be loss averse? Present biased? Regret averse? Ambiguity averse? Overconfident? Will they neglect the base rate? Are they hungry? From a predictive point of view, you have a range of countervailing biases that you need to disentangle. From a diagnostic point of view, you have an explanation no matter what decision they make. And if you can explain everything, you explain nothing.

This problem has led to the development of megastudies, whereby large numbers of interventions are trialed in a single domain. For example, a recent megastudy on gym attendance trialed 53 interventions to increase gym attendance against a control. These interventions included social norms: ‘Research from 2016 found that 73% of surveyed Americans exercised at least three times per week. This has increased from 71% in 2015′. They tested combinations of micro-incentives, whereby people were given Amazon credit for attending the gym. Some incentives were loss-framed in that the experimental participants were told that they were given a certain number of points and would lose them if they did not attend. The largest effect was generated in the intervention group where incentives were provided for returning to the gym after a missed workout. By testing many interventions in a common context, the megastudy provides a method to filter which are more effective.

There is clearly a need for studies of this type. When health experts, behavioral practitioners, and laypeople predicted the results of the megastudy interventions on gym attendance, there was no relationship between their predictions and the results. In a more recent megastudy on vaccine take-up, behavioral scientists were similarly unable to predict the results. If you can’t predict, you need to test. Surprisingly, laypeople were able to predict which vaccine interventions were more effective. Common sense, at least in this application, provided a better predictive tool than the list of biases and interesting effects known to the researchers.

Outside of applied work, the lack of a theoretical framework hampers progress of behavioral economics as a science. Primarily, it means you don’t understand what it is that you are observing. Further, many disciplines have suffered from what is now called the replication crisis, for which psychology is the poster child. If your body of knowledge is a list of unconnected phenomena rather than a theoretical framework, you lose the ability to filter experimental results by whether they are surprising and represent a departure from theory. The rational-actor model might have once provided that foundation, but the departures have become so plentiful that there is no longer any discipline to their accumulation. Rather than experiments that allow us to distinguish between competing theories, we have experiments searching for effects.....

....MUCH MORE

All the Cognitive Biases In One Chart

Via the Incidental Economist:

Behavior: We Are More Rational Than Those who Try To 'Nudge' Us

I do not like the nudge people. They are manipulative, deceitful as to their true aims and goals and morph into coercive demi-tyrants whenever they spot an opportunity. No, I do not like them at all.

May 2018

And In Lieu of a Thought For The Weekend

From Existential Comics:

This might be confirmation bias, but I feel like everyone who is obsessed with constantly calling out cognitive biases are idiots.

— Existential Comics (@existentialcoms) May 10, 2018

However, for the dedicated reader who has traveled this far, a parting gift:

In Honor of E. Musk: "Announcing Free Subscriptions to FEN Behavioral & Experimental Finance Subject Matter eJournals" (TSLA)

Oh hell, there are a hundred more. If interested see:

- "Men in a mating frame of mind become less loss-averse"

- Ogilvy & Mather UK Vice-Chairman, Rory Sutherland, Talks Behavioral Economics

- Behavioral Finance at The World's First Stock Exchange

- Nobel Laureate Richard H. Thaler on the End of Behavioral Finance

-

Investing: "Have the Behaviorists Gone Too Far?"

The Rory Sutherland piece is especially worthwhile.