A repost from September 2018 just because it is so awesome.

This is a stunning piece of research.

note: this version of the map is via the Verge, HT up front to Professor Crawford's twitter feed which points up a giant wall-sized copy at the V and A.

From NYU's Kate Crawford:

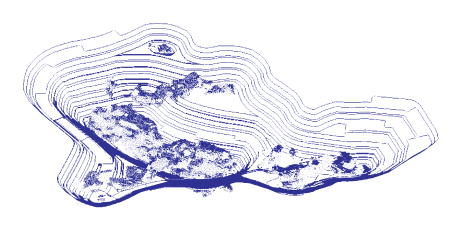

The Amazon Echo as an anatomical map of human labor, data and planetary resources

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/61251349/Screen_Shot_2018_09_07_at_5.53.10_PM.0.png)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/61251349/Screen_Shot_2018_09_07_at_5.53.10_PM.0.png)

Download map in pdf format here

I

A cylinder sits in a room. It is impassive, smooth, simple and small. It stands 14.8cm high, with a single blue-green circular light that traces around its upper rim. It is silently attending. A woman walks into the room, carrying a sleeping child in her arms, and she addresses the cylinder.

‘Alexa, turn on the hall lights’

The cylinder springs into life. ‘OK.’ The room lights up. The woman makes a faint nodding gesture, and carries the child upstairs.

This is an interaction with Amazon’s Echo device. 3 A brief command and a response is the most common form of engagement with this consumer voice-enabled AI device. But in this fleeting moment of interaction, a vast matrix of capacities is invoked: interlaced chains of resource extraction, human labor and algorithmic processing across networks of mining, logistics, distribution, prediction and optimization. The scale of this system is almost beyond human imagining. How can we begin to see it, to grasp its immensity and complexity as a connected form? We start with an outline: an exploded view of a planetary system across three stages of birth, life and death, accompanied by an essay in 21 parts. Together, this becomes an anatomical map of a single AI system.

Amazon Echo Dot (schematics)

II

The scene of the woman talking to Alexa is drawn from a 2017 promotional video advertising the latest version of the Amazon Echo. The video begins, “Say hello to the all-new Echo” and explains that the Echo will connect to Alexa (the artificial intelligence agent) in order to “play music, call friends and family, control smart home devices, and more.” The device contains seven directional microphones, so the user can be heard at all times even when music is playing. The device comes in several styles, such as gunmetal grey or a basic beige, designed to either “blend in or stand out.” But even the shiny design options maintain a kind of blankness: nothing will alert the owner to the vast network that subtends and drives its interactive capacities. The promotional video simply states that the range of things you can ask Alexa to do is always expanding. “Because Alexa is in the cloud, she is always getting smarter and adding new features.”

How does this happen? Alexa is a disembodied voice that represents the human-AI interaction interface for an extraordinarily complex set of information processing layers. These layers are fed by constant tides: the flows of human voices being translated into text questions, which are used to query databases of potential answers, and the corresponding ebb of Alexa’s replies. For each response that Alexa gives, its effectiveness is inferred by what happens next:

Is the same question uttered again? (Did the user feel heard?)

Was the question reworded? (Did the user feel the question was understood?)

Was there an action following the question? (Did the interaction result in a tracked response: a light turned on, a product purchased, a track played?)

With each interaction, Alexa is training to hear better, to interpret more precisely, to trigger actions that map to the user’s commands more accurately, and to build a more complete model of their preferences, habits and desires. What is required to make this possible? Put simply: each small moment of convenience – be it answering a question, turning on a light, or playing a song – requires a vast planetary network, fueled by the extraction of non-renewable materials, labor, and data. The scale of resources required is many magnitudes greater than the energy and labor it would take a human to operate a household appliance or flick a switch. A full accounting for these costs is almost impossible, but it is increasingly important that we grasp the scale and scope if we are to understand and govern the technical infrastructures that thread through our lives.

III

The Salar, the world's largest flat surface, is located in southwest Bolivia at an altitude of 3,656 meters above sea level. It is a high plateau, covered by a few meters of salt crust which are exceptionally rich in lithium, containing 50% to 70% of the world's lithium reserves. 4 The Salar, alongside the neighboring Atacama regions in Chile and Argentina, are major sites for lithium extraction. This soft, silvery metal is currently used to power mobile connected devices, as a crucial material used for the production of lithium-Ion batteries. It is known as ‘grey gold.’ Smartphone batteries, for example, usually have less than eight grams of this material. 5 Each Tesla car needs approximately seven kilograms of lithium for its battery pack. 6 All these batteries have a limited lifespan, and once consumed they are thrown away as waste. Amazon reminds users that they cannot open up and repair their Echo, because this will void the warranty. The Amazon Echo is wall-powered, and also has a mobile battery base. This also has a limited lifespan and then must be thrown away as waste.

According to the Aymara legends about the creation of Bolivia, the volcanic mountains of the Andean plateau were creations of tragedy. 7 Long ago, when the volcanos were alive and roaming the plains freely, Tunupa - the only female volcano – gave birth to a baby. Stricken by jealousy, the male volcanos stole her baby and banished it to a distant location. The gods punished the volcanos by pinning them all to the Earth. Grieving for the child that she could no longer reach, Tunupa wept deeply. Her tears and breast milk combined to create a giant salt lake: Salar de Uyuni. As Liam Young and Kate Davies observe, “your smart-phone runs on the tears and breast milk of a volcano. This landscape is connected to everywhere on the planet via the phones in our pockets; linked to each of us by invisible threads of commerce, science, politics and power.” 8

IV

Our exploded view diagram combines and visualizes three central, extractive processes that are required to run a large-scale artificial intelligence system: material resources, human labor, and data. We consider these three elements across time – represented as a visual description of the birth, life and death of a single Amazon Echo unit. It’s necessary to move beyond a simple analysis of the relationship between an individual human, their data, and any single technology company in order to contend with with the truly planetary scale of extraction. Vincent Mosco has shown how the ethereal metaphor of ‘the cloud’ for offsite data management and processing is in complete contradiction with the physical realities of the extraction of minerals from the Earth’s crust and dispossession of human populations that sustain its existence. 9 Sandro Mezzadra and Brett Nielson use the term ‘extractivism’ to name the relationship between different forms of extractive operations in contemporary capitalism, which we see repeated in the context of the AI industry. 10 There are deep interconnections between the literal hollowing out of the materials of the earth and biosphere, and the data capture and monetization of human practices of communication and sociality in AI. Mezzadra and Nielson note that labor is central to this extractive relationship, which has repeated throughout history: from the way European imperialism used slave labor, to the forced work crews on rubber plantations in Malaya, to the Indigenous people of Bolivia being driven to extract the silver that was used in the first global currency. Thinking about extraction requires thinking about labor, resources, and data together. This presents a challenge to critical and popular understandings of artificial intelligence: it is hard to ‘see’ any of these processes individually, let alone collectively. Hence the need for a visualization that can bring these connected, but globally dispersed processes into a single map.

V

If you read our map from left to right, the story begins and ends with the Earth, and the geological processes of deep time. But read from top to bottom, we see the story as it begins and ends with a human. The top is the human agent, querying the Echo, and supplying Amazon with the valuable training data of verbal questions and responses that they can use to further refine their voice-enabled AI systems. At the bottom of the map is another kind of human resource: the history of human knowledge and capacity, which is also used to train and optimize artificial intelligence systems. This is a key difference between artificial intelligence systems and other forms of consumer technology: they rely on the ingestion, analysis and optimization of vast amounts of human generated images, texts and videos.

...MUCH MORE (an incredible amount of work went into this)