A controversial billion-dollar citizenship-for-sale business led the elections firm to conduct clandestine campaigns across the Caribbean, insiders say.

In 2010, as elections neared in Saint Kitts and Nevis, a grainy hidden-camera video was uploaded to YouTube. In the anonymously produced clip, voters across the small Eastern Caribbean island nation saw prime minister candidate Lindsey Grant in a hotel room, listening as a British-accented property developer promises him a $1.5 million payment in exchange for a bargain price on a plot of government land.

“What we’re after is making sure you get into power,” says the developer, whose face and voice are obscured. In return, “you will help us. . . how does that sound?”

Grant, a Harvard Law School-educated lawyer running on an anti-corruption platform, appears reluctant, but eventually pushes the bribe higher, to $1.7 million. The video cuts to white text on black: “He sold his country and the people’s land just to win power.”

The video went viral in Saint Kitts, and the incumbent prime minister, Denzil Douglas, was soon re-elected for a fourth term. Douglas denied any knowledge of the sting operation, but across the Caribbean, speculation swirled that it was the work of a clandestine London-based political consultancy: SCL Group.

The now-defunct Anglo-American firm has gained notoriety for its harvesting of Facebook profiles and shady campaign tactics, but the storm of controversy has been building for decades. Before its younger sibling, Cambridge Analytica, worked for Donald Trump, SCL Group claimed to have built a portfolio of political work in three dozen countries, deploying its “behavioral change” tactics in sometimes shaky democracies.

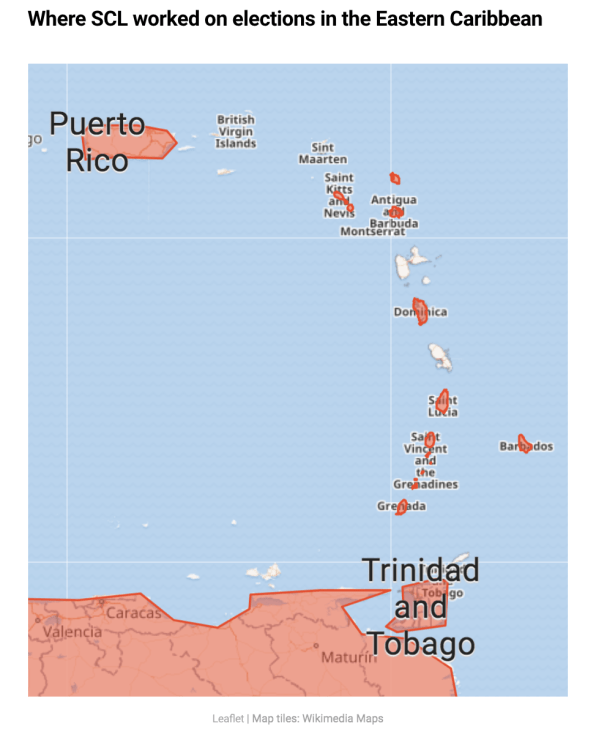

In the Eastern Caribbean, where SCL quietly operated in at least six countries, some of its work had an indirect objective: Assisting a lucrative trade in passports. The sales are legal, and lucrative, with the world’s rich thought to spend over $2 billion on “citizenship by investment,” or CBI. But reporting and interviews with industry insiders show how a nexus of buyers, officials, citizenship agents, and consultants has helped enable criminals and ignited political wildfires that continue to rage even now.

In at least five Caribbean nations, the company’s campaigns were backed by Christian H. Kalin, the chief executive of Henley and Partners, a London-based firm that markets and sells second passports, and helped support politicians thought to be sympathetic to Henley’s interests. With a friendly politician in office, according to people familiar with the arrangement, Henley could then become that country’s primary passport merchant, giving it the right to earn lucrative commissions on every sale.

“It was a particular way of achieving his strategic objective, which was to supply money and supply campaign provision to put in to power the government that would be conducive to both him and his clients,” Sven Hughes, who worked on the campaigns as SCL’s head of elections from 2009 to 2010, told Fast Company. To win elections, he said, SCL’s then-CEO Alexander Nix regularly turned to questionable techniques, including the hidden-camera video. ......MUCH MORE