Joseph Cotterill in Cape Town

The city was on the verge of becoming the first major urban centre to run out of water but has averted the crisis. But for how long, and at what cost, in a divided country?

It doesn’t look much like victory — the scorched rocks, bone-dry corpses of long-dead trees and the hot white sand stretching into the distance speak more of a scene of desolation. This is no desert. It is a dam, set in the middle of fruit orchards and golf courses in South Africa’s Western Cape province. Theewaterskloof, the biggest reservoir for Cape Town, is a diminished trickle after three years of relentless drought that have reduced it to barely a tenth of its 480bn-litre capacity. It is now possible to stroll through ghostly rows of Chenin Blanc vines submerged when the dam was flooded, in the 1970s.

It is a biblical scene. “If the world ends tomorrow and the Lord brings the fire, there won’t be the water to extinguish it,” says Rachel Erasmus, a resident of Villiersdorp, a nearby town.

Theewaterskloof shows the severity of the water crisis that threatened to turn South Africa’s second city, 120km away and with a population of nearly 4m, almost completely dry this year. In the words of Cyril Ramaphosa, speaking in January before he became South Africa’s president, Cape Town faced “real, total disaster”. In an age of climate change it was the world’s first metropolis to confront such a fate.

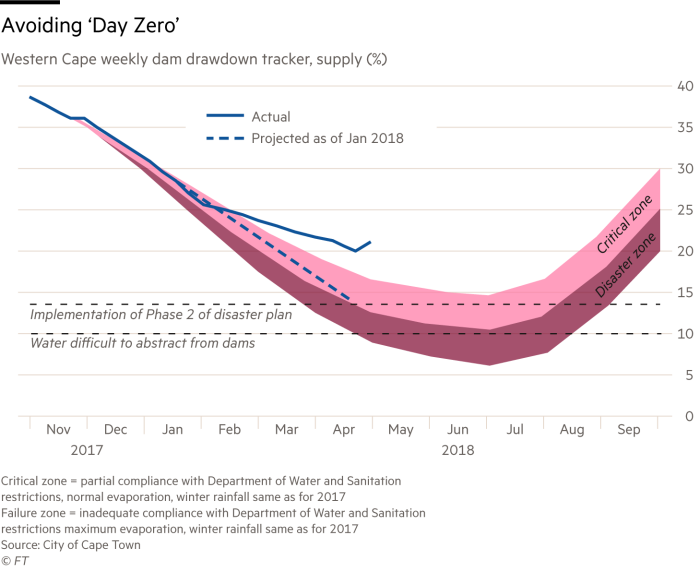

And yet, remarkably, Cape Town has averted it — for now at least. Day Zero, the disaster movie-like moment when municipal engineers would have turned off the taps for millions and forced them to queue at military-guarded standpipes, has been pushed back to 2019.

City planners had been braced as recently as February for Day Zero to arrive by April after annual rainfall dropped from an average of 1,100mm in 2013 to just 500mm last year, devastating a provincial supply system reliant, almost entirely, on the collection of surface water. Many pray enough rain will come in the next few winter months to exorcise the drought altogether.

However, respite has come not from the skies, nor the ground nor ocean through technological tricks to tap subterranean aquifers and desalinate seawater. It is largely down to one of the most drastic civic water conservation campaigns ever conceived.

In three years, Cape Town residents have more than halved their use from 1.2bn litres a day in 2015, to just over 500m litres at the start of this year — a record-breaking pace. “We’re going to become one of the world’s water-resilient cities,” says Helen Zille, the Western Cape’s provincial premier and a former mayor of Cape Town.

It has included enforcing suburban restrictions of 50 litres a day per person, versus a global average use of 185 litres, with key sectors such as tourism and agriculture bearing the brunt of scarcity. Authorities combined behavioural nudges and public praise with draconian surveillance and dire warnings.

“Water use has dropped quite amazingly,” says Neil Armitage, a professor of civil water engineering at the University of Cape Town. “We will definitely make this year. If we have another dry year as bad as the last, it looks as though we could survive it again. People didn’t like being treated like naughty children. But it worked.”

It has been a close-run thing. Day Zero, under which residents would have been rationed to 25 litres a day, would have been triggered when overall dam levels fell to 13.5 per cent. They are currently at 19 per cent. Facing a future that is more urban, more unequal and straining at ecological limits, cities in the developing world may look to Cape Town for lessons. If they do, they will find a parable — about a young democracy facing tough decisions over sharing scant resources, while addressing injustices from its past and institutional failings in its present....MUCH MORE