Above: Near-neutral conditions across the tropical

Pacific were evident in this depiction of seasonally adjusted

sea-surface heights for April 24, 2018, as measured by a radar-based

altimeter aboard NASA's Jason-3 satellite. During El Niño, the warmer

upper-ocean conditions across the eastern equatorial Pacific lead to

higher sea-surface heights and a characteristic large belt of bright

red. In the image above, the higher-than-average heights between the

equator and California correspond to a strongly positive Pacific

Meridional Mode (see discussion below). Image credit: NASA.

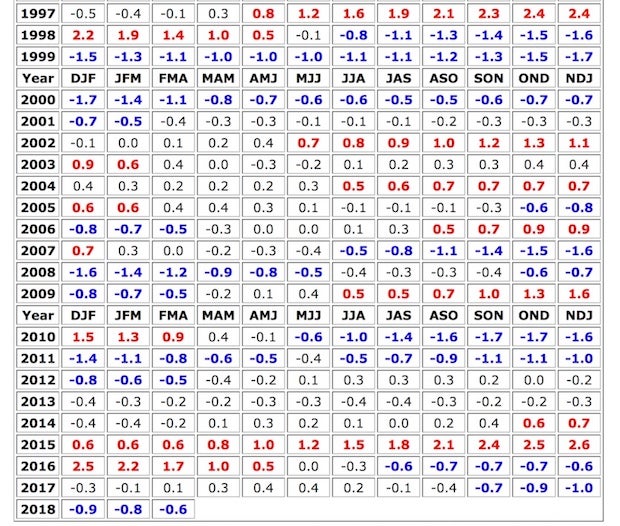

La Niña conditions no longer existed in the tropical Pacific Ocean, with cool-neutral conditions prevailing in April, said NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center (CPC) in its May 10 monthly advisory. The weak La Niña event that began in August 2017 is now over, something the Australian Bureau of Meteorology concurred with in their April 13 biweekly report. The bureau uses a more stringent threshold than NOAA for defining La Niña: sea-surface temperatures in the Niño3.4 region of the tropical Pacific must be at least 0.8°C below average, vs. the NOAA benchmark of 0.5°C below average.

Over the past week, sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the benchmark Niño 3.4 region (in the equatorial Pacific) were about 0.4°C below average, which is outside the 0.5°C to 1.0°C-below-average range that is required to qualify as a weak La Niña. Odds for an El Niño event to form are predicted to increase as we head towards the fall and winter of 2018, with the latest CPC/IRI Probabilistic ENSO Forecast calling for a 38% chance of an El Niño event during the August-September-October peak of the Northern Hemisphere hurricane season. El Niño events typically reduce Atlantic hurricane activity, due to an increase in wind shear over the tropical Atlantic.

|

| Figure 1. Sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the benchmark Niño3.4 region (in the equatorial Pacific) have hovered around 0.4°C below average over the past week, outside of the 0.5° - 1.0°C below average range required to be classified as weak La Niña conditions. Image credit: Levi Cowan, tropicaltidbits.com. |

Still no guarantee of El Niño for 2018-19

We’re still in the midst of the spring predictability barrier, the time of year when forecasting the future of El Niño and La Niña is toughest. Recent climatology (see Figure 2 below) suggests that it’s more likely for a second-year La Niña event like 2017-18 to segue into either neutral or El Niño conditions than to be followed by a third winter of La Niña conditions. The CPC/IRI outlook reflects this split: by the winter of 2018–19 (December through February), it predicts a roughly 50% chance of El Niño, a 40% chance of neutral conditions, and a 10% chance of La Niña.

|

| Figure 2. El Niño and La Niña episodes since 1997. Each cell in the grid above shows the three-month average SST in the Niño3.4 region. To qualify as an El Niño or La Niña episode, at least five consecutive three-month periods must meet the respective threshold. Image credit: NOAA/NWS/CPC. |

There were signs early this year of a potential shift to El Niño with the arrival of an extraordinarily strong Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO) in the western Pacific. It led into a downwelling Kelvin wave, a slow-moving pulse of warmer-than-average water that translated from west to east just below the surface of the equatorial Pacific. Sometimes an MJO and Kelvin wave can weaken trade winds and realign atmospheric and oceanic circulations enough to kick off an El Niño event. This MJO didn’t do the trick, possibly because it occurred a bit too early in the seasonal cycle, but it did hasten the demise of the 2017-18 La Niña event....

...MUCH MORE