One way to get to know a sales rep is to study his expense account. Jean-François Favarger’s expenses, calculated carefully in the French currency of livres, sous, and deniers, appear at the end of his diary. They provide a preview of his journey.

Before setting out on his horse, he had his coat repaired: 1 livre, 3 sous disbursed in La Neuveville, his hometown, ten miles north of Neuchâtel, on July 3, 1778, two days before he took to the road. The garment probably was a redingote (riding coat), a solid piece of cloth waxed to withstand rain, not at all comparable to the finery that gentlemen wore, with fancy trimming and double rows of well-wrought buttons. Favarger needed protection from the elements. They were kind to him on the first leg of the journey. But in August, when he reached the lower valley of the Rhône, the sun beat down on him relentlessly and the redingote probably was tied across his saddlebags. Favarger encountered very little water, even in riverbeds, until September 6, when he entered Carcassonne. Then it began to pour. From Toulouse to La Rochelle, it hardly stopped. Favarger had to buy a new hat: 10 livres. And he had put up with so much friction in the saddle that he also had to purchase a new pair of breeches: 26 livres, both for the breeches and for a quilt to get him through the chilly nights that set in at the beginning of October. The roads were then so muddy that his horse slipped and fell several times a day. He took to leading it by the bridle and walked so far under such bad conditions that he wore through his boots: 3 livres, 3 sous for resoling. Sweating under the summer sun in Languedoc and shivering through the autumn muck in Poitou, Favarger did not cut much of a figure on the road. He probably smelled when he arrived at country inns. Only twice on the entire circuit did he enter expenses for laundry: 1 livre, 10 sous in Toulouse and 1 livre, 4 sous in Tonneins—the rough equivalent each time of a day’s wages for one of the Société typographique de Neuchâtel’s printers. He carried a hunting knife and a brace of pistols, which he had worked over by a gunsmith in Marseilles—10 sous—after being warned about highwaymen on the road to Toulon.

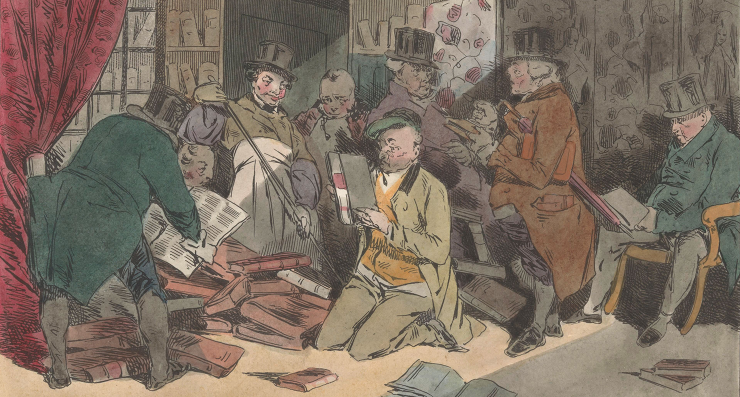

Not that Favarger looked like a highwayman himself, despite the dirt and dust that accumulated on his redingote. He had to be presentable when he walked into a well-appointed bookshop on the high street of a city. After his arrival in Lyon, he bought himself a suit with a waistcoat: 23 livres, 4 sous, 6 deniers for fabric (“voile” or light cotton) and tailoring. That was an important sum for a clerk—5 percent of his annual wages—but not an extravagance. Further along his route he treated himself twice to ribbons (12 sous each) for binding the tress of hair that he wore down the back of his neck. He was not the sort to wear a wig or carry a sword. Like many journeymen, however, he had a watch: repaired in September for 2 livres, 8 sous. And when in company, he exchanged his boots for shoes: he purchased a new pair for 4 livres, 10 sous in Toulouse. Favarger’s expense account provides a rare opportunity to picture someone from the lower strata of society two centuries ago. Yet the picture quickly blurs. We do not know the color of his eyes.

It is possible, however, to form some notion of the young man’s character. The style of his letters is straightforward and unadorned, the grammar and penmanship excellent, as befitted a clerk. Favarger must have had a good basic education, though he did not attempt the rhetorical flourishes and literary allusions that sometimes decorated the letters of his superiors, the directors of the Société typographique, who were accomplished men of letters. His was a business correspondence, so one should not read too much into it. But insofar as it expressed a turn of mind, it suggests someone serious, eager to please, hard-working, and rather self-effacing. Favarger took the world in at street level, eyeing it squarely and describing it in no-nonsense language: subject, verb, predicate. On rare occasions he showed a touch of humor. He characterized the book inspector of Marseilles as “one of those men who would eat his brother in order to have a meal,” and Buchet, a bookseller in Nîmes, as “something of a camera obscura.” But he did not go in for figurative language and rarely used the colloquialisms peculiar to the book trade—expressions such as the compliment that he paid to Malherbe, an illegal book dealer in Loudun: “He is very good at selling his shells” (“Il sait fort bien vendre ses coquilles”)....MORE

Tuesday, February 6, 2018

"An Agent of Enlightenment: The business of books in 1778 France, as seen by a sales representative for a Swiss publishing house"

From Laphams Quarterly, February 5: