The IPO priced at $16 back in April 2015 so it is still a bit underwater but is suddenly interesting, I mean beyond the ongoing availability of witches curses at the platform, despite the ban....From Bloomberg:

“There is one and only one social responsibility of business,” the economist Milton Friedman famously wrote in 1962. And that is “to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits.” Those words helped establish the now pervasive idea that companies are exclusively responsible, within the limits of the law, to the people who own them. Even the most soft-hearted public-company chief executive treats the idea with a measure of respect. In March, at his final annual meeting, Starbucks Corp. CEO Howard Schultz declared that, notwithstanding his plans to hire refugees and open stores in poor neighborhoods, the company’s commitment to shareholder value remained “absolute.”But there are exceptions. “You’re all free to hiss,” Chad Dickerson said after quoting Friedman in a speech at a corporate social responsibility conference in late 2014. Dickerson, then the 42-year-old chairman and CEO of Etsy Inc., paused for a moment, as the audience hissed and laughed. Then, for good measure, he hissed himself.

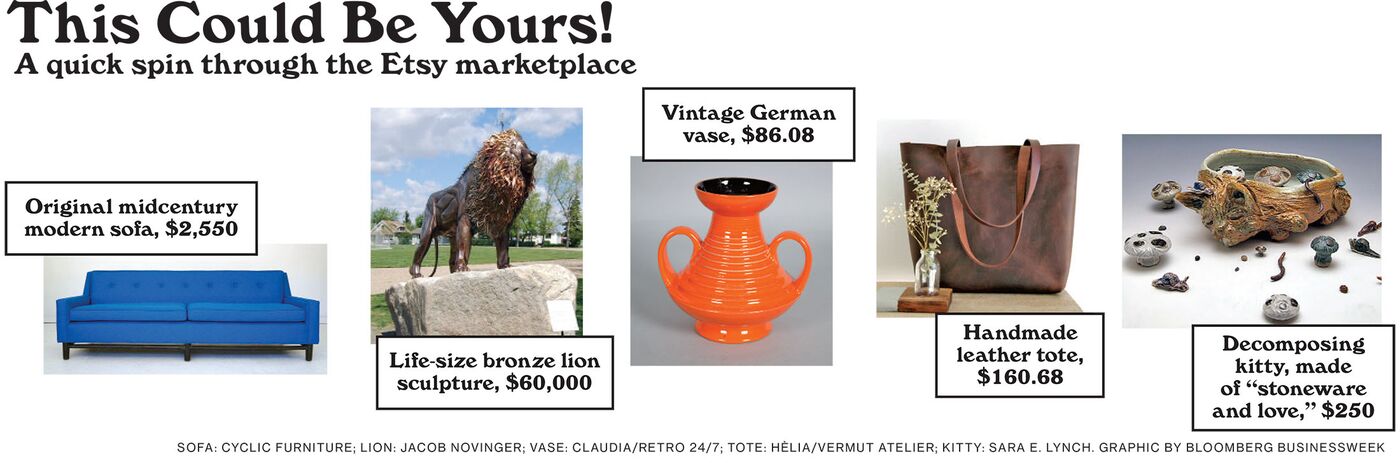

At the time of the speech, Dickerson, a former journalist with soft features and a laid-back demeanor, was preparing to take Etsy public. Founded in 2005, the Brooklyn-based online marketplace hosts 1.8 million small merchants who sell vintage and handmade goods and takes a cut of every transaction. Its sellers traffic in the one-off items usually found in antique stores and boutiques: pineapple-motif throw pillows, succulent-shaped jewelry, tote bags with birds on them. The fast-growing market is often mocked as a kind of twee EBay—TweeBay, if you will. But by early 2015 the company was selling close to $2 billion in merchandise a year and generating revenue of $196 million—figures that had more than doubled from two years earlier.

... MUCH MOREUnder Dickerson’s leadership, Etsy had not only grown quickly, it had also won a reputation as an ethical company, becoming a certified B Corporation in 2012. The do-gooder seal of approval, given out by the nonprofit B Lab, requires a business to meet standards related to the environment, workers, and suppliers. Some 2,000 companies are B Corps—including Patagonia, Warby Parker, and Kickstarter—but almost all are privately held. Today there are just a handful of public B Corps; Etsy is one of only two traded on a major U.S. exchange.

Public-market B Corps are rare because investors hate them. As part of the certification, a company must reject the shareholder valuation model and, eventually, reincorporate as a “public-benefit corporation.” (To keep its B Corp seal, Etsy will have to commit to reincorporating this summer. Dickerson said in a 2016 interview that this was unlikely.) Benefit corporations are structured so managers and board members have a legal obligation to worry about more than just their fiduciary duty to shareholders. A public-benefit corporation can get sued for wasting shareholder money just like a normal public company can, but it can also be sued for being a poor steward of the environment or for failing to pay a fair wage.

When Etsy filed for an initial public offering, it limited the value of the shares retail investors could buy to $2,500 per person. The idea was to make sure shares were available to Etsy sellers and to create a shareholder base that would be sympathetic to Dickerson’s vision of a more conscientious brand of capitalism. But Dickerson also believed that big institutional investors, who make up most of its shareholder base, could be convinced that Etsy’s community focus and B Corp status weren’t incompatible with growth and profitability. “We understand the concern, but reject the premise,” he wrote in a blog post published the day of the IPO in April 2015. “Etsy’s strength as a business and community comes from its uniqueness in the world and we intend to preserve it. We don’t believe that people and profit are mutually exclusive.”

For about 24 hours, Dickerson’s comments looked prescient. In Etsy’s first day as a Nasdaq-listed company, its market value doubled, to more than $3 billion. But in the two years that followed, the stock fell 63 percent. Whatever investors thought about Dickerson’s take on capitalism, they also felt strongly about accelerating revenue growth, and they got the opposite: It fell from 44 percent in the first quarter of 2015 to 25 percent in the last quarter of 2016.

Late last year the company’s struggles caught the attention of Seth Wunder, a tech investor and hedge fund manager based in Los Angeles. In Etsy, Wunder saw a business that was fundamentally sound. A similar model had worked spectacularly well for EBay Inc., which had made money for 21 straight years—and Etsy arguably had a much better brand. It has more Instagram followers than EBay, Macy’s, and Home Depot, and more website traffic than Target. How, Wunder asked, was Etsy not making more money?...

Previously:

Today In Artisanal: Etsy is Up 22% (ETSY)

Signposts: "Etsy Pivots From Crunchy Hipster To Gordon Gekko In One Afternoon" (ETSY)

Etsy Drops 7.77% On News It's Still Etsy (ETSY)

We actually have quite a bit on this one including the older, never-to-be-topped DealBreaker headline:

"Etsy’s Stock Is A Découpage of Market Schadenfreude" (ETSY)