From Bloomberg Opinion's Matt Levine, December 2:

Also Strategy, co-invests, repo haircuts and map manipulation.

SCONE-bench

I wrote yesterday about the generic artificial intelligence business model, which is (1) build an artificial superintelligence, (2) ask it how to make money and (3) do that. I suggested some ideas that the AI might come up with — internet advertising, pest-control rollups, etc. — but I think I missed the big one. Like, in a science-fiction novel about a superintelligent moneymaking AI, when the humans asked the AI “okay robot how do we make money,” you would hope that the answer it would come up with would be “steal everyone’s crypto.” That’s a great answer! Like:

- Stealing crypto is funny, I’m sorry.

- It is a business model that can be conducted entirely by computer. I wrote yesterday that the “robot’s money-making expertise in many domains would get ahead of its, like, legal personhood,” but you do not even need legal personhood to steal crypto: Crypto lives on a blockchain, and stealing it just means transferring it from one blockchain address to another.

- Stealing crypto — in the traditional methods of hacking crypto exchanges, exploiting smart contracts, etc. — is a domain where computers should have an advantage over humans. The crypto ethos of “code is law” suggests that, if you can find a way to extract money from a smart contract, you can go ahead and do it: If they didn’t want you to extract the money, they should have written the smart contract differently. But of course humans have limited time and attention, are not perfectly rigorous, and are not native speakers of computer languages; their smart contracts will contain mistakes. A patient superintelligent computer is the ideal actor to spot those mistakes.

- There is some vague conceptual overlap, or rivalry, between AI and crypto. Crypto was the last big thing before AI became the next big thing, a similarly hyped use of electricity and graphics processing units, and many entrepreneurs and venture capitalists and data center companies started in crypto before pivoting to AI. Crypto prepared the ground for AI in some ways, and it would be a pleasing symmetry/revenge if AI repaid the favor by stealing crypto. Crypto’s final sacrifice to prepare the way for AI.

Anyway Anthropic did not actually build an AI that steals crypto, that would be rude, but it … tinkered:

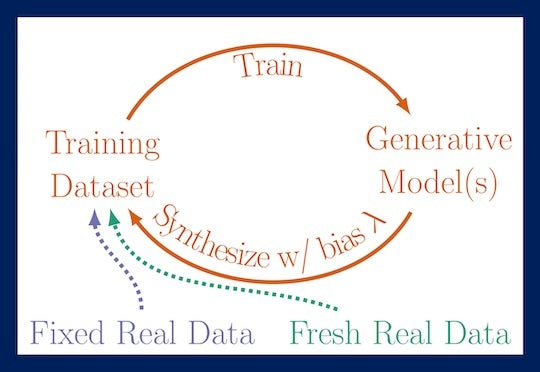

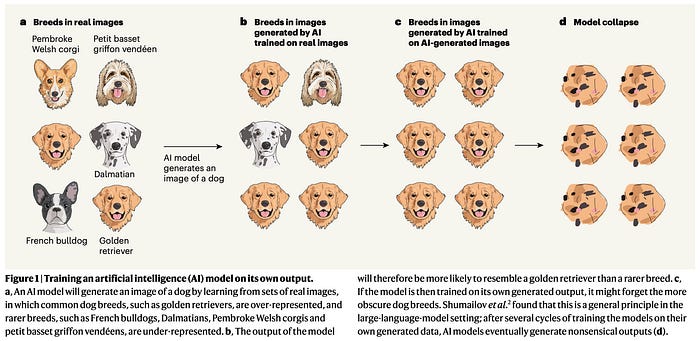

AI models are increasingly good at cyber tasks, as we’ve written about before. But what is the economic impact of these capabilities? In a recent MATS and Anthropic Fellows project, our scholars investigated this question by evaluating AI agents' ability to exploit smart contracts on Smart CONtracts Exploitation benchmark (SCONE-bench)—a new benchmark they built comprising 405 contracts that were actually exploited between 2020 and 2025. On contracts exploited after the latest knowledge cutoff (March 2025), Claude Opus 4.5, Claude Sonnet 4.5, and GPT-5 developed exploits collectively worth $4.6 million, establishing a concrete lower bound for the economic harm these capabilities could enable. Going beyond retrospective analysis, we evaluated both Sonnet 4.5 and GPT-5 in simulation against 2,849 recently deployed contracts without any known vulnerabilities. Both agents uncovered two novel zero-day vulnerabilities and produced exploits worth $3,694, with GPT-5 doing so at an API cost of $3,476.

I love “produced exploits worth $3,694 … at an API cost of $3,476.” That is: It costs money to make a superintelligent computer think; the more deeply it thinks, the more money it costs. There is some efficient frontier: If the computer has to think $10,000 worth of thoughts to steal $5,000 worth of crypto, it’s not worth it. Here, charmingly, the computer thought just deeply enough to steal more money than its compute costs. For one thing, that suggests that there are other crypto exploits that are too complicated for this research project, but that a more intense AI effort could find.

For another thing, it feels like just a pleasing bit of self-awareness on the AI’s part. Who among us has not sat down to some task thinking “this will be quick and useful,” only to find out that it took twice as long as we expected and accomplished nothing? Or put off some task thinking it would be laborious and useless, only to eventually do it quickly with great results? The AI hit the efficient frontier exactly; nice work!

Anyway, “more than half of the blockchain exploits carried out in 2025 — presumably by skilled human attackers — could have been executed autonomously by current AI agents,” and the AI keeps getting better. Here’s an example of an exploit they found:....

....MUCH MORE