A repost from September 2020:

A topic I may be overly intrigued by.

In my defense, I may be dissolute but the dissolution is strictly commercial. One of my favorite stories along these lines was in January 4's "Britain, India, and Cannabis":

Via The Public Domain Review, an essay:

If interested see also:

In my defense, I may be dissolute but the dissolution is strictly commercial. One of my favorite stories along these lines was in January 4's "Britain, India, and Cannabis":

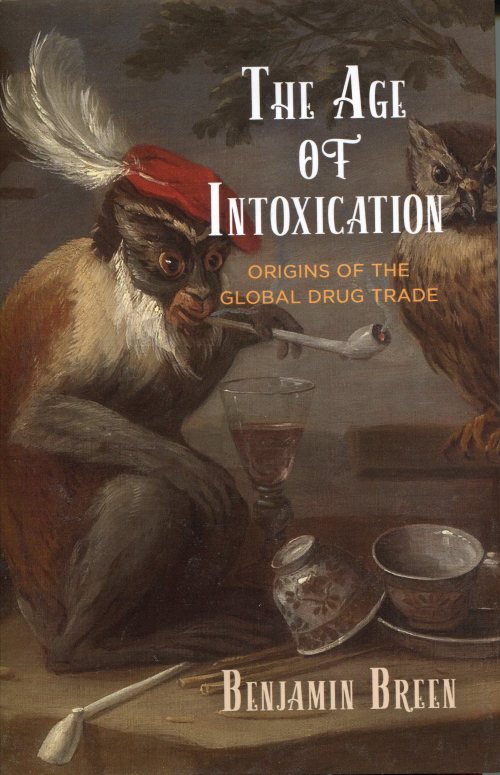

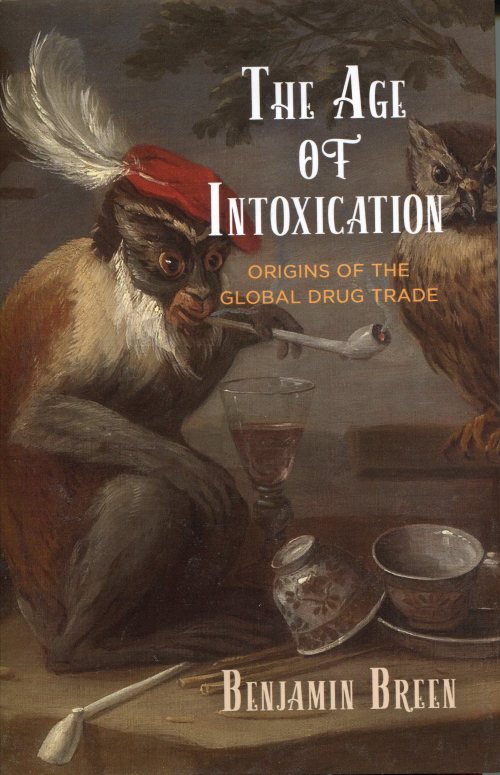

Today's selection -- from The Age of Intoxication by Benjamin Breen.That's right, the first thing he thinks isn't some quasi-mystical hoo-haw, it's "Damn, I bet I could sell this shit!"

In 1673, the days in which Britain is first starting to extend its influence to India, a young Brit named Thomas Bowrey encounters cannabis on the coast of India. His first thoughts are to commercialize the substance:...

Via The Public Domain Review, an essay:

In the 17th century, English

travelers, merchants, and physicians were first

introduced to cannabis,

particularly in the form of bhang, an intoxicating edible

which

had been getting Indians high for millennia. Benjamin Breen charts the

course of the drug from the streets of Machilipatnam to the scientific

circles of

London.

Published

February 19, 2020

View

of Masulipatam, published by Johannes Janssonius Waasbergen, 1672. The

three flags indicate the location of foreign trading factories — Source.

Not long after he arrived in Machilipatnam, Thomas Bowrey began to wonder what it was that the people of Machilipatnam were smoking.The bustling port city on India’s Coromandel Coast felt fantastical to the young East India Company merchant. During the first days of his visit in 1673, Bowrey marveled at wonders like “Venomous Serpents [which] danced” to the tune of “a Musicianer, or rather Magician", and “all Sortes of fine Callicoes...curiously flowred”.1 Above all, Bowrey was most fascinated by the effects of an unfamiliar drug. The Muslim merchant community in the city was, as Bowrey put it, “averse [to]...any Stronge [alcoholic] drinke”. Yet, he noted, “they find means to besott themselves Enough with Bangha and Gangah", i.e. cannabis. Gangah, though "more pleasant", was imported from Sumatra (and as such was "Sold at five times the price"), whereas Bangha, "theire Soe admirable herbe”, was locally grown. The word Bangha came to be more commonly transliterated as bhang, and nowadays generally refers specifically to an edible preparation (usually a drink). It is not clear whether Bowrey uses the word with such a specific meaning in mind but either way it is this liquid form, "the most pleasant way of takeinge it", which he opts to experiment with, as opposed to smoking it, which he describes (with perhaps some trepidation) as a “a very speedy way to be besotted".Bowrey initially compared the effects of the drug to alcohol. Yet it seemed that bhang's properties were more complex, “Operat[ing] accordinge to the thoughts or fancy” of those who consumed it. On the one hand, those who were “merry at that instant, shall Continue Soe with Exceedinge great laughter”, he wrote, “laughinge heartilie at Every thinge they discerne”. On the other hand, “if it is taken in a fearefull or Melancholy posture”, the consumer could “seem to be in great anguish of Spirit”. The drug seemed to be a kind of psychological mirror that reflected — or amplified — the inner states of consumers. Small wonder, then, that when Bowrey resolved to try it, he did so while hidden in a private home with “all dores and Windows” closed. Bowrey explained that he and his colleagues feared that the people of Machilipatnam would “come in to behold any of our humours thereby to laugh at us”.2

Detail from Sea Captains Carousing in Surinam (ca. 1755), a painting by John Greenwood executed on a bedsheet — Source.

Bowrey’s account of the resulting effects is worth quoting at length:....MUCH MORE

It Soon tooke its Operation Upon most of us, but merrily, Save upon two of our Number, who I suppose feared it might doe them harme not beinge accustomed thereto. One of them Sat himself downe Upon the floore, and wept bitterly all the Afternoone; the Other terrified with feare did runne his head into a great Mortavan Jarre, and continued in that posture 4 hours or more; 4 or 5 of the number lay upon the Carpets (that were Spread in the roome) highly Complementinge each Other in high terms, each man fancyinge himselfe noe lesse then an Emperour. One was quarralsome and fought with one of the wooden Pillars of the Porch, untill he had left himself little Skin upon the knuckles of his fingers.3Reckless self-experimentation with drugs is sometimes assumed to be a modern practice. Accounts like Bowrey’s disabuse us of this notion. Bowrey and his merchant friends were plainly interested in bhang as a recreational intoxicant, even if three of Bowrey’s group seem to have found the experience to be less than optimal — to put it mildly.Bowrey, who would later author the first English dictionary of the Malay language, was what his contemporaries called a “philosophical traveler”.4 His interest in cannabis lay not only in its recreational value but in its “curiosity” as a wondrous substance with hidden properties. He was also keenly interested in discovering substances with the potential to be commodified. However, converting a drug like cannabis into a global commodity was not easy. The drug was embedded in a local spiritual and cultural framework — Bowrey himself seems to have viewed it as a distinctively Muslim substance. The England of Bowrey’s time was shot through with paranoia and prejudice relating to fears of both Catholic conspirators and Muslim (specifically, Ottoman Turkish) invaders. Nevertheless, forging alliances with both Portuguese Catholics and Muslims was essential for British merchants seeking a foothold in the East Indies. Bowrey’s primary contact in Machilipatnam had been “Petro Loveyro, an antient Portuguees", who Bowrey said he came to “[know] very well.” Petro, along with Bowrey’s Muslim bodyguard, may have played a role in Bowrey’s introduction to cannabis....

If interested see also:

The Swinging '60's (1660s)with the cover art of Breen's book featuring this chap: