From The Antiplanner, February 3:

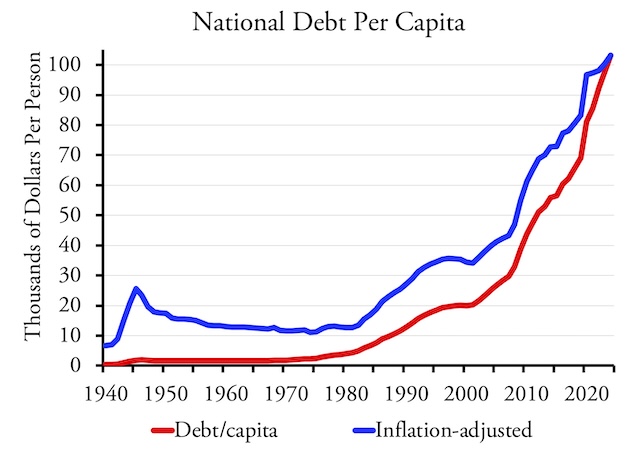

The national debt is more than $36 trillion, which is about $110,000 for every man, woman, and other-gendered person in the United States. When I was in high school, the national debt was about $1,800 per person, and I remember wondering if I could afford to pay my share. At that time, it might have been possible to pay it off with a one-time tax on everyone; today, not so much.

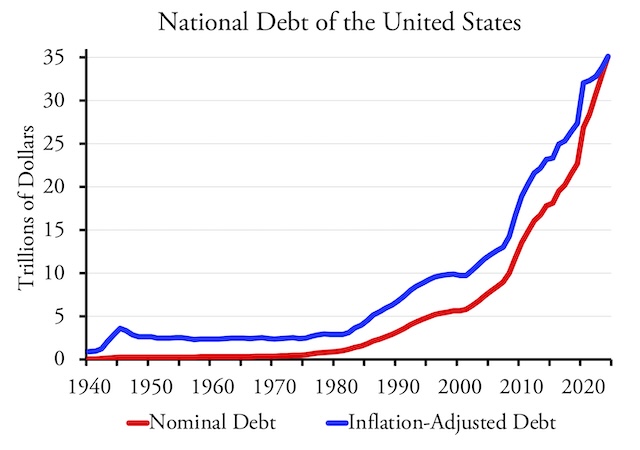

Before World War II, the U.S. had a long history of going into debt during wartime and then paying off most of that debt between wars. The above chart shows that after 1945 we paid off some of the war-related debt, but then entered a 1984-like world of permanent hot or cold war, which led Congress to give up any notion of completely paying off the debt. Still, as shown in the chart below, after adjusting for inflation the debt per capita continued to decline until around 1974.

Since 1974, the debt has grown increasingly out of control. The “Modern Monetary Theorists” who say this is perfectly healthy are as insane as anyone who thinks a diet of three all-you-can-eat meals a day at the Golden Corral could be healthy. The Department of Government Efficiency has the self-assigned task of reversing this trend, but to do so it needs to understand how we got here in the first place and why previous attempts to solve the problem failed.

Demographer Peter Zeihan blames it on the Baby Boomers. He points out that people consume in their 20s, 30s, and 40s, and that consumption leads to increased tax revenues for government. People save in their 50s and 60s, which provides the capital to support the consumer economy. After people retire, they become much more cautious with their savings, making little contribution to the economy or tax flows to government. As long as there is a balance of generations, however, the economy should work fine.

The large number of Baby Boomers created an imbalance. When they were young, they generated huge economic growth. In their middle years they provided the capital for such things as the digital economy. Now that they are retired or retiring, however, the economy threatens to stagnate.

So far that sounds reasonable. But Zeihan then says that the tax revenues generated by young Baby Boomers “allowed for the expansion of the government under Johnson and Nixon and Reagon. During this time, the Boomers, because the cash flows were robust, built a larger and larger welfare state” that mainly benefitted themselves. That welfare state can’t be supported now that the Boomers are retiring. The problem with this notion is that the national debt started going out of control in the mid-1970s, when Baby Boomers were still in their 30s. Why would increasing cash flows to government lead to increasing deficits? Zeihan offers lots of useful insights, but this isn’t one of them.

A Yale economist named Ray Fair blames the Baby Boomers for a different problem: a decline in infrastructure spending. Fair estimates that this decline began “around 1970” and that it represents a change that made the United States “less future oriented.” (In economic terms, the social discount rate increased so the future was less valued than the present.)

A less future-oriented country would help explain why deficit spending rapidly increased. If you don’t care about the future, it makes perfect sense to borrow and spend now. Fair speculates this happened because “the counterculture movement, triggered in large part by the Vietnam war and the draft, led to a change in tastes, in particular more negative views about the establishment and the government.” Infrastructure declined, Fair says, because people no longer trusted government. But if they didn’t trust government, then why did government spending increase so rapidly?

I don’t accept either Zeihan’s or Fair’s explanations. Instead, I think that budgetary trends reflect institutional designs....

....MUCH MORE