Speculation has its own expiration dynamics, and they don't depend on us recognizing speculative excess for what it is. They will unravel the excesses regardless of what we think, hope or deny.

The Federal Reserve has so completely normalized speculative excess that these extremes are no longer even recognized as extremes. Rather, they are simply "the way the world works." This Empire of Speculation is complex and plays out on multiple levels.

The primary mechanism is obvious to all: whenever the equity market falters, the Fed unleashes a flood tide of liquidity, i.e. fresh currency, that rushes into the market at the top--corporations, banks and financiers--because the Fed distributes the fresh liquidity solely into the top tier of market players.

The Fed's ability to conjure up liquidity in a variety of ways appears limitless: expand its balance sheet (QE), use the reverse repo market and bank reserves, launch new lending mechanisms, and so on.

The Fed has long relied on useful fictions to mask its agenda. One useful fiction is that the Fed is independent and apolitical. Despite being risibly shopworn, this mirth-inducing fiction is still dutifully trotted out by every Fed chairperson.

Another useful fiction is that the Fed's mandate focuses on promoting stable expansion of the economy, not the equity market. This masks the reality everyone knows and acts on, which is the market isn't a reflection of the economy, it is the economy.

This is why the Fed will pursue ever greater policy extremes to rescue the market from any decline and keep equity markets lofting higher: should the market falter, the economy will quickly follow, as the animal spirits of the market are now the primary engine of expansion.

The Fed's focus on inflating the equity markets entered a new phase of policy extremes in 2008, a phase that continues to this day. The Fed's willingness to "do whatever it takes" time and again has created a feedback loop that has expanded the influence of the market on the economy and the Fed's influence on the market, to the point that the market is now keyed to every Fed utterance and policy tweak.

The market rallies on the expectation of Fed pauses, Fed easing, Fed bank bailouts, and so on: every Fed action sparks a rally because everyone knows there are no limits on what the Fed will do to further inflate the equity market.

Speculative gains are not actually growth in the sense of increasing productivity and wages in the real economy. Much of what passes for "growth" is actually profiteering by corporate monopolies, corporate trickery (stock buybacks, etc.) that boost earnings per share without actually producing more goods, services or productivity, corporations reaping the gains of offshoring production, financiers using the Fed's flood tide of liquidity to skim gains while producing nothing, and so on.

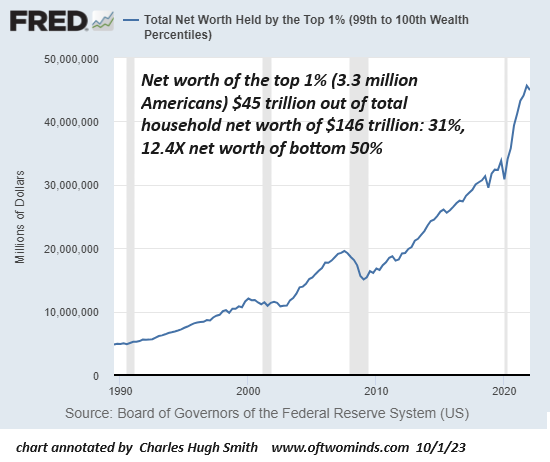

This is not the "growth" generated by the expansion of productivity, it's a phony simulacra of "growth" generated by Fed-liquidity-driven skims and scams. The only possible outcome of this dynamic is the soaring concentration of wealth and income in the hands of those with access to the Fed's flood tide: the already-super-wealthy, which is exactly what has happened.

These dynamics have drawn the entire populace into the Fed's speculative casino. With the real economy's productivity stagnating, the only way to get ahead is to join the crowd in the casino. Everybody's playing, one way or another. In the 1929 analogy, every shoeshine boy and taxi driver was working a hot new speculation. Now it's every Uber jockey and delivery driver....

The demon speculation, scattering wild booms and still wilder panics, hovers over us as the abiding affliction of our machine age. Yesterday it was the demon of disease sweeping periodically across great continents, or the demon of scarcity arising from the niggardliness of earth in the face of mounting populations. From these and from other similar afflictions science has set us free, only to leave us in the sardonic plight where fertility and the oversupply of every commodity from petroleum to silk, under the hand of the playboy speculation, have become abundant sources not of happiness but of misery. Seemingly a savage jest is being played upon our self-sure, scientific generation.

For speculation is the ghost of everything abhorrent to science in industry, which worships, before all else, foresight and cautious calculation. And yet scientific business leadership seems able to do no more than attempt to talk speculation to death by cryptic public appeals. Our communist friends in the meantime praise speculation as the borer that will surely destroy the tree of capitalism. Our moralists anathematize it furiously as human effort gone wrong, because the end which it seeks to attain—gain through quick wits rather than through slow toil—is ethically indefensible. Our psychologists dismiss speculation as a minor phase of mob psychology. Our politicians and our bankers blame each other and everyone else for fomenting rather than curbing the evil. Yet the ebb and flow of speculation, in regular cycles, go on without check and give promise of going on disastrously.

This passion for speculation, seemingly innate in human nature, must be viewed apart from certain more basic causes of our present business distress. For speculation is not a controlling force. Rather it seems akin to an impenetrable fog that periodically settles down upon the busy channels of business activity, causing innumerable collisions and widespread blindness. It quickens or retards basic economic tendencies instead of creating them. It destroys by causing our business leaders and our investors, and above all our investment and our commercial bankers, to ascend to dizzy heights self-delusion only to plunge helplessly and hopelessly toward the pits disaster. Thus, scientific industrial acumen is deflected from the control and adjustment of those more basic factors which are retarding and shaping our modern civilization of wealth. Technological unemployment due the substitution of machines for men, with the consequent ills of a steadily increasing army of unemployed; distortions of the direction of commodity prices by reason of a lagging and insufficient production of gold or by reason of the sterilization of our existing supplies of gold through nationalist provincial outlook; disturbances arising from stupidly adjusted war debts or from tariff barriers; the ever-pressing problem, in an industrial age, of devising consumption to absorb the waxing output of improved productive machinery, born of technical skill and accumulated earnings—these riddles of our modern age must be considered from speculation. The demon of speculation is merely the bull in the china shop which raises havoc with all schemes and all devices to understand master such economic tendencies. Our immediate economic task, therefore, is to make progress toward fettering this mad disturber.

But can speculation be fettered? Are we dealing with human emotions which defy control? Certainly we cannot fetter speculation by our naïve American tendency immediately to enact a law. Making short selling—a that bête noire of the amateur economist—a crime, or attempting to forbid speculation in securities by imposing a heavy tax upon the resale of stock recently purchased, would obviously be impractical as well as futile in a democratic state. So, too, an effort to distort and distend the functions of the Federal Reserve System, by charging it with the power and duty to ration supplies of credit to the stock market, would be an unworkable and paternalistic venture.

But to dismiss speculation despairingly as mass madness which descends the public in recurrent waves, and to insist that such mob folly is incurable, must remind one of the medievel attitude of despair toward the great plagues that then raged through Europe. The havoc and poignant suffereing which these whirlwinds of speculation leave in millions of hearts call for at least an attempt at more than a fatalistic, primitive-minded meekness. One thing at least can be made clear by a survey of the monotonous regularity of the internal processes of speculation—its roots run far deeper than the shallow soil of the public’s emotions and intelligence.

For speculation is but a necessary and a beneficent human instinct gone wrong. So long as we have an individualistic, capitalistic system, the impelling force to human action in industry must be a self-reliant though discerning eagerness to profit personally. And as a part of such an economic system there must be an adequate flexibility permitting unrestrained freedom, on the part of those who manage and invest, to buy and sell the elements of wealth—commodities, land, securities. Fraud and coercion the State can restrain; but, unless we wish to go the road toward communism, the State must leave every buyer and every seller free to act as wisely or as foolishly as his intellectual and emotional capacities dictate.

In the last ten years we have had in America three unequaled uprushes and collapses of speculation in the three chief elements of wealth: commodities, land, and securities. After the Great War, in 1919 to 1920, we suffered a mad speculation primarily in commodities, although there were great accompanying excesses in securities. Shortly after that bitter experience, we rushed into a mad and unparalleled speculation in land in Florida. We are closing these eventful ten years with a unique, international economic disaster, partly resulting from six years of turbulent, world-wide speculation in American common stocks. The record is a dismal one. It becomes dismaying if we must fear that during the next decade we must reel under similar periodic whirlwinds.

Ten years ago America became the economic master of humanity, and Wall Street the financial centre of the world. Have we proved adequate to the heavy burden of power and responsibility thus assumed? Were our English friends farseeing when they consoled themselves with the prophecy that our banking inexperience and our emotional, financial ineptitude would force us to let unparalleled advantages fall from our hands? The past decade of speculative excesses must at least suggest that we scrutinize speculation objectively and dispassionately, in its relation to our American financial methods, if we would glimpse the future of American financial supremacy and of American prosperity.

The first stage in each of the three outbursts of speculation which occurred during the past ten years was an apparently miraculous opportunity for industries and investors permanently to enlarge earnings, or profits on re-sales, through a deep-seated though sudden change in economic tendencies. These economic changes to the calm observer seemed superficial and illusory; but, by reason of the staggering profits made by those who acted on the contrary conviction, even the wise were led to distrust their own reasoning.

In 1919, because of novel economic factors created by the long war, the demands of the American market for luxuries and for general commodities seemed so vast and unending as to be certain of continuing in increasing vigor for several years—even for several decades . . . . Next, we concluded that a great migration of population was in process that would suddenly convert Florida, America’s most backward and neglected pioneer state, into an Arcadia of mingled play and industry. Or we accepted Pollyanna assurances that an abundance of gold and of credit and prosperity meant that everyone would invest in land and at the same time take a winter vacation—in Florida . . . . And finally, four years ago, we became convinced, once and for all, that the earnings of our great industries—by reason of the magic of a superior business technique directing superior machines—would expand miraculously, without rest or interruption. Silly conceptions these all seem to-day; yet the initial profits made by those who accepted these extravagant theories were more potent than experience or reason. Such is the outstanding characteristic of the first stage of speculation—momentary results are more potent than logic.

The second stage of each of these speculations was a seemingly urgent scarcity of the units of speculation—commodities or real-estate lots or sound common stocks—and an outburst of imaginative eloquence in picturing the results of an enduring scarcity. Reasons for the continuance of any scarcity are never lacking. Suave, even sincere propaganda, in the guise of ultramodern economic theory, always becomes a characteristic of the second phase of speculation. For these new economic theories become part of the sales propaganda of those who imprudently, rather than maliciously, exploit the opportunities offered by the new economic era.

Because of this fancied scarcity of the units of speculation, and because of the consequent mad scramble to acquire them, the basis of computing price factors in this second stage is slowly, though boldly, changed. No longer are prices fixed by the usual method of utility—the capitalization of the income obtained as rents or dividends from land or stocks by multiplying such income by some such numeral as ten. No longer are the prices of commodities fixed by the standard of what they can be resold for in manufactured form. Slowly, optimistically, we tend to accept, as the master index of value, the price at which the unit of speculation can be resold to other speculators. Market prices and market trends become supreme. The conservative speculator, who seeks to delude himself into believing that he is buying solely for a long investment holding, is largely controlled by the conviction that prices will mount, without more than minor fluctuations, in about the same general ratio as in the immediate past. Without much difficulty he convinces himself that earnings and therefore prices will increase yearly after the manner of an arithmetical progression....

....MUCH MORE, as I've said at the jump on other recent posts, he's only getting started.

At

the time this was written the equity market as measured by the Dow

Jones Industrial Average had been cut by more than half: 381 top-tick in

September 1929 to 169.89 on April 2, 1931. (-55.3%)