That's the question people were asking during World War I.

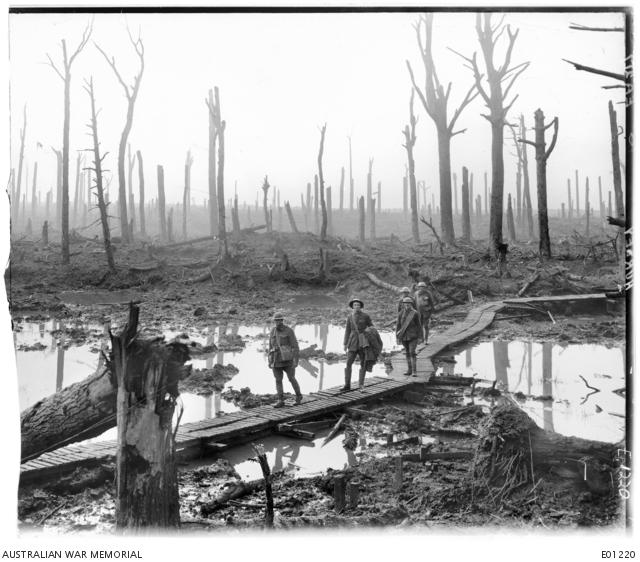

The mud.

It was probably worst in Belgium, Ypres I-V (Passchendaele was Ypres III)And because of the incompressibility of water the muck itself became a

weapon, acting as a solid when forced through human tissue by

explosions. Nasty business for the surgeons as well as the wounded.

From The Atlantic Magazine, September 01, 1916:

It is a commonplace of conversation that for some months past the weather conditions have been abnormal, particularly in the matter of rainfall, in the battle-zones and elsewhere. Detailed data from regions close to the firing lines are not available; and we have only general statements of inclemency in so far as they affect military operations. But in districts not far away,—the British Isles, for instance,—the records of excessive raininess during the winter of 1914-15 and at subsequent times have not escaped comment; and others besides meteorologists are discussing the possibility of a connection between the heavy cannonading and the rainfall. The professional meteorologist is called upon to answer whether there is any rational explanation of what appears to be a marked departure from the usual sequence of weather conditions. Is it possible that the tremendous expenditure of ammunition—an expenditure which the layman may well regard as an experiment in concussion sufficiently vast to be decisive—has facilitated condensation and its later stage, precipitation? In concise terms, has the bombarding not only caused clouds but forced the clouds to send down rain?

It is conceivable that such could be the case; and stranger things have happened than the revelation through war of fresh progress in man's effort to comprehend and master the processes of Nature. And here, as is so often the case, Nature herself has suggested the relation, for we have all noticed that after an exceptionally near and heavy clap of thunder, the raindrops fall with a rush, as if the very tumult had shaken the clouds and caused the downpour. Later we shall see how this well-known phenomenon is to be interpreted.

Three separate lines of inquiry suggest themselves as throwing light on the problem. First, the underlying principles of the formation and flotation of a drop of rain; second, the causes of excessive rainfall in certain places at certain times; and third, the direct relation, if any, which exists between the use of high explosives and showery or rainy weather. To most of us the raindrop is an ordinary, commonplace drop of clean water, or rather it seems to be clean. It is one of the most common phenomena of everyday life, and most of us never stop to think that its life-history could be eventful; in fact we are sure that there can be nothing unusual about a drop of water falling through the air. On the contrary there is much that is wonderful in the wanderings of the little visitor; and the structure of each minute globe is in its way as marvelous as the structure the great nebula in Andromeda....

....MUCH MORE

Those commentators he speaks of hadn't seen the half of it. The battle of Passchendaele/Third Battle of Ypres was coming up, July 31 to November 6, 1917:

Wikimedia Commons Morning a Passchendaele

As mentioned in an earlier post,

the Menin Gate Memorial To The Missing stands in tribute to the 55,000

British and Commonwealth troops who died in and around Ypres that were

never found, drowned in the mud, atomized by high explosives, just

disappeared and have no known grave. That's 55,000 disappeared of the

400,000 casualties of the three Battles of Ypres. Another 34,959 are named at nearby Tyne Cot Memorial to the Missing.

Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria, the Field Marshal commander facing the Canadians, Australians, British and New Zealanders noted in his diary;

12 October 1917

'Witterungsumschlag. Erfreulicherweise Regen, unser wirksamster bundesgenosse.'

(Sudden change of weather. Most fortunate rain, our most effective ally)

That "earlier post" hyperlink has some archival material that may be of interest.