We've already looked at the political responses to rising gasoline prices:

ICYMI: To Battle Gasoline Price Inflation The U.S. Will Burn More Food

Who Is Buying The First 30 Million Barrels Of Oil In The Latest Release From The Strategic Petroleum Reserve?

As we said three weeks ago:

"Apparently the cure for high prices is upcoming mid-term elections"

And diesel? From Doomberg, April 27:

Diesel for Dinner

“Governing a great nation is like cooking a small fish - too much handling will spoil it.” – Lao Tzu

The words edible and eatable are often used interchangeably but embedded within their respective definitions is a distinction that makes an important difference. Edible means “safe to eat,” whereas eatable means “pleasant to eat.” A variant of the word eatable is delicious, commonly defined as “highly pleasant to eat.” Delicious certainly sounds more enticing than highly eatable, a phrase nobody would use to compliment an exquisite meal crafted by a professional chef. We find such linguistic nuances pleasing.

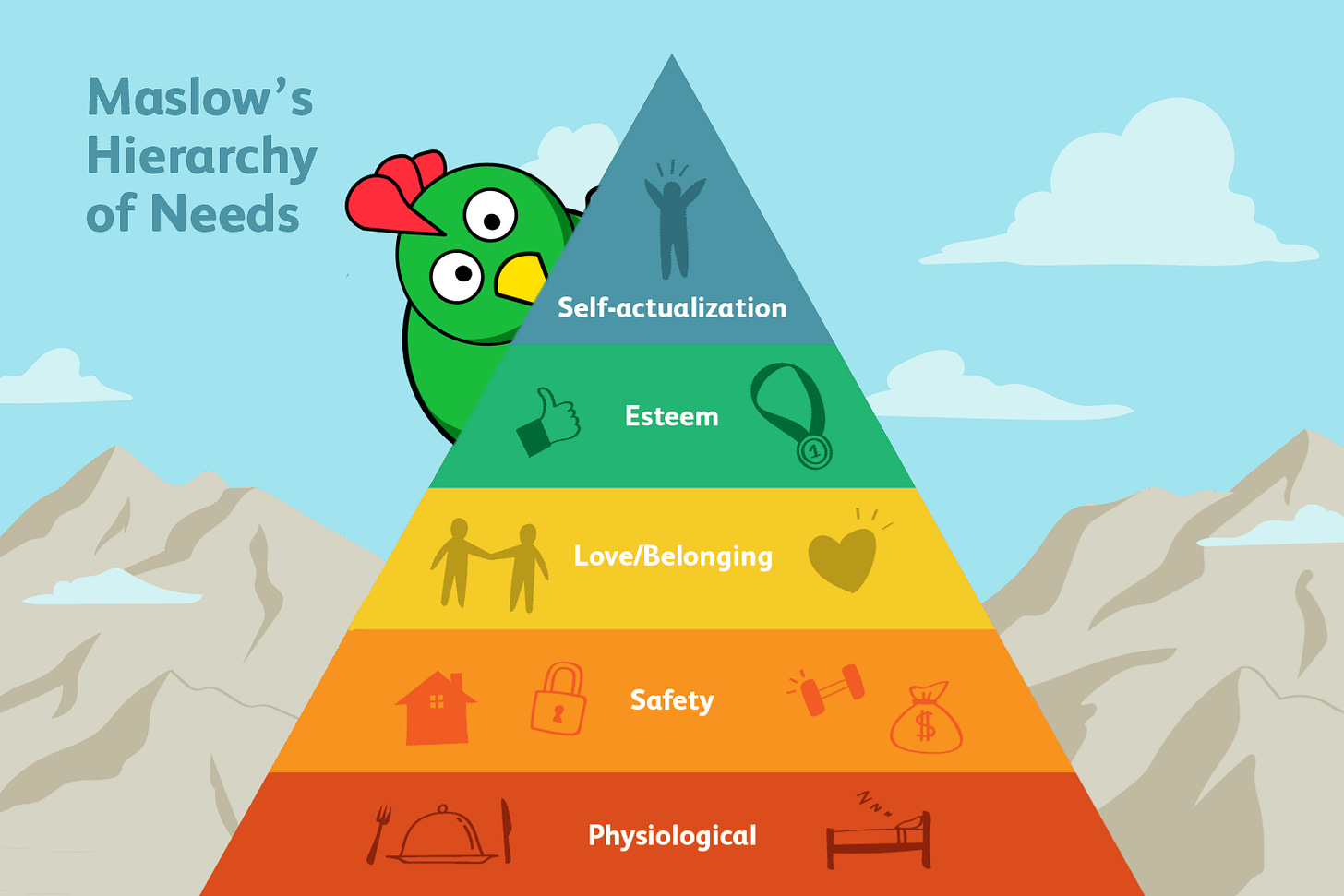

Whether the balance of calories a person consumes is edible, eatable, or delicious depends on where they sit on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, a concept we covered at length in a piece we wrote last July called Why Are Cows Sacred? For those at the base of the pyramid, the struggle to consume enough edible food just to see another sunrise defines much of their existence. At the top of the pyramid sit those fortunate souls who can afford to cook delicious meals with fresh ingredients, eat at fine restaurants, or even hire a personal chef to tend to their every dietary indulgence.

At the molecular level, the distinction between edible and inedible can be subtle. The rearrangement of a few atoms within an otherwise similar chemical structure can make the difference between satiation and a trip to the emergency room. Prior to the advent of the modern chemical and energy industries, humanity leveraged animal and plant byproducts to create many of the functional materials used in daily life, making the tradeoff between food and other needs a more visceral one than it is today. The edible parts were eaten, and the inedible stuff – presumably identified through an unfortunate series of trial and error experiments – was converted into other useful things or burned to create energy.

Armed with humanity’s mastery of chemistry, we can now rearrange atoms with astonishing specificity at an unimaginable scale, pushing billions of people further up Maslow’s hierarchy than they would otherwise be. In addition to using fossil fuels to create most of the materials that surround us, we leverage them to produce fertilizers, herbicides, fungicides, and other inputs into the farming process, boosting crop yields to levels once thought impossible. We also synthesize mountains of edible ingredients directly from oil and gas. Touring a modern food processing factory would seem almost indistinguishable from a specialty chemical plant, mostly because they aren’t all that different.*****While it makes perfect sense to leverage our bounty of fossil fuels and ability to manipulate them at the molecular level to increase global food abundance, going through the effort to grow food only to turn around and burn it for energy seems less than ideal. In a controversial piece we wrote in January titled “In Praise of Corn Ethanol,” we put forth a theory that the adoption of corn ethanol as a mandated additive to gasoline was a scheme to coverup one of the greatest environmental scandals of the past century: the use of tetraethyl lead as an anti-knock agent. While some readers interpreted our piece as supporting this policy – undoubtedly because of the title – our primary purpose was to highlight the ugly history that got us to the current situation, and how it was predominantly a dirty political compromise. In hindsight, “Why Corn Ethanol is a Thing” might have been a better title.No such compromise underpins the decision to use foodstuffs as replacements for diesel, a policy that will make the unfolding global food crisis substantially worse if it is not soon overturned.

When a barrel of oil is refined, it is separated into various products using the different boiling points of its components. Gasoline boils at a lower temperature than diesel and represents about 43% of each barrel of oil. Diesel makes up approximately 27%, with the other 30% destined to become heating oil, jet fuel, asphalt, and other important materials. Because of its higher energy density per gallon and the efficiency of engines designed to use it, diesel is a desirable fuel, especially for long-haul trucking....

....MUCH MORE

Way back in April 2008, the U.S. was still in Afghanistan and Iraq, Gaddafi in Libya and Morsi in Egypt had not yet been overthrown, the Maidan coup in Ukraine was six years in the future and the Russian invasion was fourteen years ahead, the price of oil was going parabolic on the charts, on its way to the record futures print, $147+, and I was thinking about substitution and pseudo-fungibility:

What Proportion of Food Price Increases is Attributable to Ethanol?

If I recall correctly it takes about five gallons of fuel to plant and harvest an acre of corn (I just spent 60 seconds trying to remember if that was conservation tillage or traditional. Then I realized that farm management was not the focus of this post, I'll go with 5 gal./acre), so the argument that rising input prices is a factor has merit....

Some things never change. But they should

Related, noted in a 2015 post:

Remember, the rule of thumb is it takes around 10 crude oil calories to produce 1 row crop (mainly corn and soybeans) calorie.

Most other food prices are similarly dependent on their input costs.

One oft-cited bit of nuttines is the fact it takes 127 calories of aviation fuel to get a head of lettuce from California to London....