But none of the climate simulations carried out for the IPCC produced

this particular hiatus at this particular time. That has led sceptics —

and some scientists — to the controversial conclusion that the models

might be overestimating the effect of greenhouse gases, and that future

warming might not be as strong as is feared. Others say that this

conclusion goes against the long-term temperature trends, as well as

palaeoclimate data that are used to extend the temperature record far

into the past. And many researchers caution against evaluating models on

the basis of a relatively short-term blip in the climate. “If you are

interested in global climate change, your main focus ought to be on

timescales of 50 to 100 years,” says Susan Solomon, a climate scientist

at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge.

But

even those scientists who remain confident in the underlying models

acknowledge that there is increasing pressure to work out just what is

happening today. “A few years ago you saw the hiatus, but it could be

dismissed because it was well within the noise,” says Gabriel Vecchi, a

climate scientist at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric

Administration’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory in Princeton, New

Jersey. “Now it’s something to explain.”

Researchers have followed various leads in recent years, focusing mainly on a trio of factors: the Sun

1, atmospheric aerosol particles

2 and the oceans

3.

The output of energy from the Sun tends to wax and wane on an 11-year

cycle, but the Sun entered a prolonged lull around the turn of the

millennium. The natural 11-year cycle is currently approaching its peak,

but thus far it has been the weakest solar maximum in a century. This

could help to explain both the hiatus and the discrepancy in the model

simulations, which include a higher solar output than Earth has

experienced since 2000.

An unexpected increase

in the number of stratospheric aerosol particles could be another

factor keeping Earth cooler than predicted. These particles reflect

sunlight back into space, and scientists suspect that small volcanoes —

and perhaps even industrialization in China — could have pumped extra

aerosols into the stratosphere during the past 16 years, depressing

global temperatures.

Some have argued that

these two factors could be primary drivers of the hiatus, but studies

published in the past few years suggest that their effects are likely to

be relatively small

4, 5.

Trenberth, for example, analysed their impacts on the basis of

satellite measurements of energy entering and exiting the planet, and

estimated that aerosols and solar activity account for just 20% of the

hiatus. That leaves the bulk of the hiatus to the oceans, which serve as

giant sponges for heat. And here, the spotlight falls on the equatorial

Pacific.

Blowing hot and cold

Just before the hiatus took hold, that region had turned unusually warm

during the El Niño of 1997–98, which fuelled extreme weather across the

planet, from floods in Chile and California to droughts and wildfires in

Mexico and Indonesia. But it ended just as quickly as it had begun, and

by late 1998 cold waters — a mark of El Niño’s sister effect, La Niña —

had returned to the eastern equatorial Pacific with a vengeance. More

importantly, the entire eastern Pacific flipped into a cool state that

has continued more or less to this day.

Just before the hiatus took hold, that region had turned unusually

warm during the El Niño of 1997–98, which fuelled extreme weather across

the planet, from floods in Chile and California to droughts and

wildfires in Mexico and Indonesia. But it ended just as quickly as it

had begun, and by late 1998 cold waters — a mark of El Niño’s sister

effect, La Niña — had returned to the eastern equatorial Pacific with a

vengeance. More importantly, the entire eastern Pacific flipped into a

cool state that has continued more or less to this day.

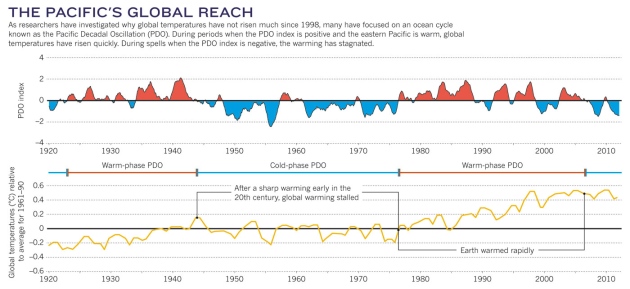

This

variation in ocean temperature, known as the Pacific Decadal

Oscillation (PDO), may be a crucial piece of the hiatus puzzle. The

cycle reverses every 15–30 years, and in its positive phase, the

oscillation favours El Niño, which tends to warm the atmosphere (see

‘The fickle ocean’).

After a couple of decades of releasing heat from the eastern and

central Pacific, the region cools and enters the negative phase of the

PDO. This state tends towards La Niña, which brings cool waters up from

the depths along the Equator and tends to cool the planet. Researchers

identified the PDO pattern in 1997, but have only recently begun to

understand how it fits in with broader ocean-circulation patterns and

how it may help to explain the hiatus.

One

important finding came in 2011, when a team of researchers at NCAR led

by Gerald Meehl reported that inserting a PDO pattern into global

climate models causes decade-scale breaks in global warming

3.

Ocean-temperature data from the recent hiatus reveal why: in a

subsequent study, the NCAR researchers showed that more heat moved into

the deep ocean after 1998, which helped to prevent the atmosphere from

warming

6.

In a third paper, the group used computer models to document the flip

side of the process: when the PDO switches to its positive phase, it

heats up the surface ocean and atmosphere, helping to drive decades of

rapid warming

7.

A

key breakthrough came last year from Shang-Ping Xie and Yu Kosaka at

the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California. The duo

took a different tack, by programming a model with actual sea surface

temperatures from recent decades in the eastern equatorial Pacific, and

then seeing what happened to the rest of the globe

8.

Their model not only recreated the hiatus in global temperatures, but

also reproduced some of the seasonal and regional climate trends that

have marked the hiatus, including warming in many areas and cooler

northern winters.

“It was actually a

revelation for me when I saw that paper,” says John Fyfe, a climate

modeller at the Canadian Centre for Climate Modelling and Analysis in

Victoria. But it did not, he adds, explain everything. “What it skirted

was the question of what is driving the tropical cooling.”

![[image]](http://barrons.wsj.net/public/resources/images/ON-BD502_GT1012_NS_20140129152756.jpg)