From the science-lovers-and-proud-of-it at The New Atlantis, Spring 2023 edition:

Special Series

Reality: A Post-Mortem

What Was "the Fact?"

Here lies a beloved friend of social harmony (ca. 1500–2000). It was nice while it lasted.

— Alasdair MacIntyre

How hot is it outside today? And why did you think of a number as the answer, not something you felt?

A feeling is too subjective, too hard to communicate. But a number is easy to pass on. It seems to stand on its own, apart from any person’s experience. It’s a fact.

Of course, the heat of the day is not the only thing that has slipped from being thought of as an experience to being thought of as a number. When was the last time you reckoned the hour by the height of the sun in the sky? When was the last time you stuck your head out a window to judge the air’s damp? At some point in history, temperature, along with just about everything else, moved from a quality you observe to a quantity you measure. It’s the story of how facts came to be in the modern world.

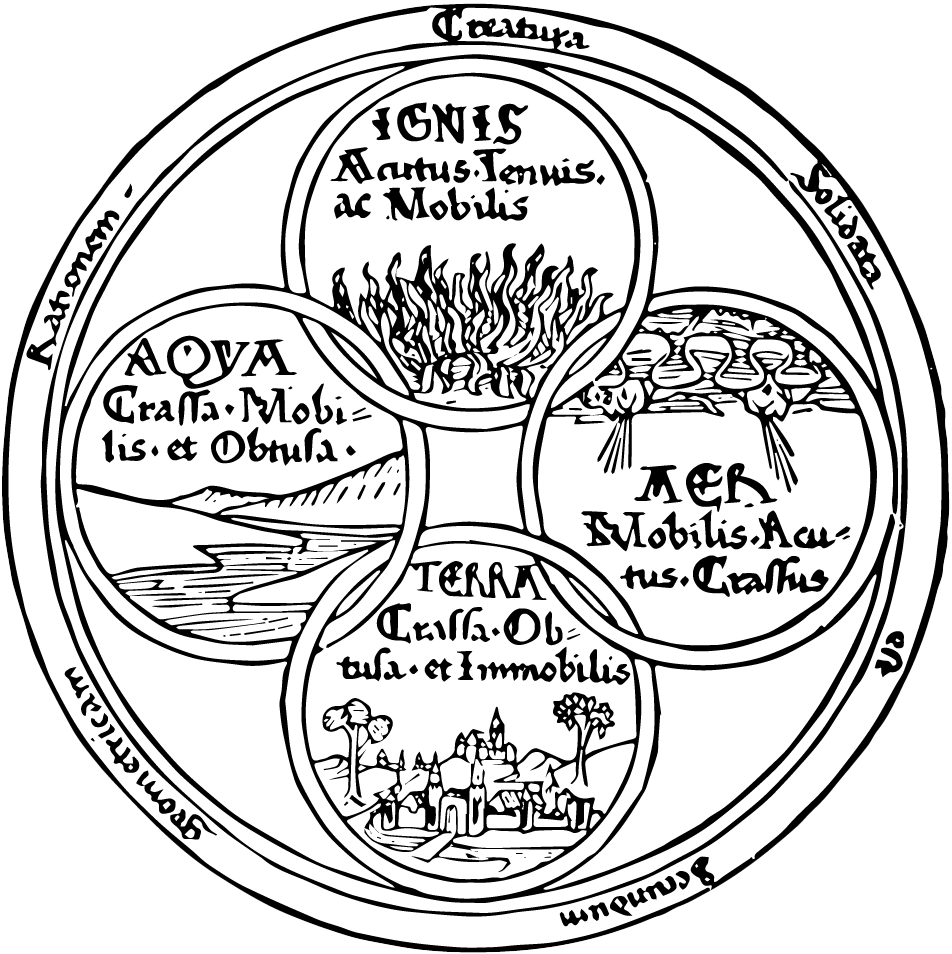

This may sound odd. Facts are such a familiar part of our mental landscape today that it is difficult to grasp that to the premodern mind they were as alien as a filing cabinet. But the fact is a recent invention. Consider temperature again. For most of human history, temperature was understood as a quality of hotness or coldness inhering in an object — the word itself refers to their mixture. It was not at all obvious that hotness and coldness were the same kind of thing, measurable along a single scale.

The rise of facts was the triumph of a certain kind of shared empirical evidence over personal experience, deduction from preconceived ideas, and authoritative diktat. Facts stand on their own, free from the vicissitudes of anyone’s feelings, reasoning, or power.

The digital era marks a strange turn in this story. Today, temperature is most likely not a fact you read off of a mercury thermometer or an outdoor weather station. And it’s not a number you see in the newspaper that someone else read off a thermometer at the local airport. Instead, you pull it up on an app on your phone from the comfort of your sofa. It is a data point that a computer collects for you.

When theorists at the dawn of the computer age first imagined how you might use technology to automate the production, gathering, storage, and distribution of facts, they imagined a civilization reaching a new stage of human consciousness, a harmonious golden age of universally shared understanding and the rapid advancement of knowledge and enlightenment. Is that what our world looks like today?

You wake to the alarm clock and roll out of bed and head to the shower, checking your phone along the way. 6:30 a.m., 25 degrees outside, high of 42, cloudy with a 15 percent chance of rain. Three unread text messages. Fifteen new emails. Dow Futures trading lower on the news from Asia.

As you sit down at your desk with a cup of Nespresso, you distract yourself with a flick through Twitter. A journalist you follow has posted an article about the latest controversy over mRNA vaccines. You scroll through the replies. Two of the top replies, with thousands of likes, point to seemingly authoritative scientific studies making opposite claims. Another is a meme. Hundreds of other responses appear alongside, running the gamut from serious, even scholarly, to in-joke mockery. All flash by your eyes in rapid succession.

Centuries ago, our society buried profound differences of conscience, ideas, and faith, and in their place erected facts, which did not seem to rise or fall on pesky political and philosophical questions. But the power of facts is now waning, not because we don’t have enough of them but because we have so many. What is replacing the old hegemony of facts is not a better and more authoritative form of knowledge but a digital deluge that leaves us once again drifting apart.

As the old divisions come back into force, our institutions are haplessly trying to neutralize them. This project is hopeless — and so we must find another way. Learning to live together in truth even when the fact has lost its power is perhaps the most serious moral challenge of the twenty-first century.

I. Scarcity: Before the Fact

Our understanding of what it means to know something about the world has comprehensively changed multiple times in history. It is very hard to get one’s mind fully around this.

In flux are not only the categories of knowable things, but also the kinds of things worth knowing and the limits of what is knowable. What one civilization finds intensely interesting — the horoscope of one’s birth, one’s weight in kilograms — another might find bizarre and nonsensical. How natural our way of knowing the world feels to us, and how difficult it is to grasp another language of knowledge, is something that Jorge Luis Borges tried to convey in an essay where he describes the Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge, a fictional Chinese encyclopedia that divides animals into “(a) those that belong to the Emperor, (b) embalmed ones, (c) those that are trained, … (f) fabulous ones,” and the real-life Bibliographic Institute of Brussels, which created an internationally standardized decimal classification system that divided the universe into 1,000 categories, including 261: The Church; 263: The Sabbath; 267: Associations. Y. M. C. A., etc.; and 298: Mormonism.

The fact emerged out of a shift between one such way of viewing the world and another. It was a shift toward intense interest in highly specific and mundane experiences, a shift that baffled those who did not speak the new language of knowledge. The early modern astronomer and fact-enthusiast Johannes Kepler compared his work to a hen hunting for grains in dung. It took a century for those grains to accumulate to a respectable haul; until then, they looked and smelled to skeptics like excrement.

The first thing to understand about the fact is that it is not found in nature. The portable, validated knowledge-object that one can simply invoke as a given truth was a creation of the seventeenth century: Before, we had neither the underlying concept nor a word for it. Describing this shift in the 2015 book The Invention of Science: A New History of the Scientific Revolution, the historian David Wootton quotes Wittgenstein’s Tractatus: “‘The world is the totality of facts, not of things.’ There is no translation for this in classical Latin or Elizabethan English.” Before the invention of the fact, one might refer, on the one hand, to things that exist — in Latin res ipsa loquitur, “the thing speaks for itself,” and in Greek to hoti, “that which is” — or, on the other hand, to experiences, observations, and phenomena. The fact, from the Latin verb facere, meaning to do or make, is something different: As we will come to understand, a fact is an action, a deed.

How did you know anything before the fact? There were a few ways....

....MUCH MORE