From Geopolitical Monitor, April 16:

Kra Canal: The Impossible Dream of Southeast Asia Shipping

The idea of the Kra Canal has been a topic of discussion for

centuries, as the promise of an alternative route between the Andaman

Sea and Gulf of Thailand could revolutionize shipping and reshape

regional geopolitics.

While the project has never come to fruition, its potential impact keeps

it in strategic conversations, particularly in light of China’s

expanding influence in Southeast Asia and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). As of now, Thailand has opted for a different path, but debates over the canal’s feasibility and geopolitical consequences remain very much alive.

Historical Background

The concept of the Kra Canal dates back to 1677

when Thai King Narai commissioned French engineer de Lamar to survey

the Kra Isthmus for a possible canal. At the time, the idea was not to

connect the Gulf of Thailand with the Andaman Sea but rather to

establish a navigable waterway between Songkhla and Marid (now Myanmar).

De Lamar’s assessment concluded that the mountainous terrain, dense

jungles, and the technological limitations of the era rendered the

project unfeasible. The immense effort required to dig through the

isthmus using 17th-century engineering methods made construction

virtually impossible, leading to its abandonment.

In the 19th century, as European colonial powers expanded their

influence in Southeast Asia, the concept of the Kra Canal resurfaced.

The British, who controlled key maritime trade routes through Singapore

and the Strait of Malacca, viewed any alternative shipping channel with

suspicion. They feared that a canal through Thailand would weaken

Singapore’s strategic importance and threaten British dominance in

regional trade. Meanwhile, France, eager to strengthen its presence in

Indochina, saw the canal as a way to establish a stronger foothold in

the region and counterbalance British influence. However, the Siamese

government, wary of foreign intervention and territorial disputes,

strategically resisted both British and French involvement. By carefully

balancing diplomatic relations with European powers while preserving

its sovereignty, Siam managed to prevent any progress on the canal

during this period.

Kra Canal in the Contemporary Context

The Kra Canal attracted renewed interest

in 1972 when an American firm, Tippetts-Abbett-McCarthy-Stratton

(TAMS), proposed a 102-km-long canal connecting Satun to Songkhla. This

proposal was driven by the need for an alternative shipping route to

alleviate congestion in the Malacca Strait and provide a more direct

maritime passage between the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea. The

plan involvedadvanced engineering techniques of the time, envisioning a

deep-water canal capable of handling large cargo vessels and oil

tankers. However, with a projected cost of $5.6 billion and a projected

10–12 year construction period, the Thai government ultimately rejected

the plan. Concerns included the massive financial burden, environmental

impact, and the risk of regional instability, particularly stemming from

foreign influence and internal security challenges.

More recently, China has become increasingly interested in reviving the project as part of its Maritime Silk Road initiative, a key component of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). In 2015, an MoU was signed

between private entities from China and Thailand to explore the

feasibility of the canal, highlighting its potential to reshape trade

routes and reduce reliance on the Malacca Strait. However, both

governments quickly distanced themselves

from the agreement, likely due to political sensitivities and

opposition from regional players like Singapore and India. The canal

never progressed beyond preliminary discussions. As of 2025, Thailand

has instead opted to prioritize a $28 billion land bridge project—an

overland transport corridor designed to facilitate cargo movement

between the Gulf of Thailand and the Andaman Sea. This alternative aims

to achieve similar economic benefits without the political and

environmental challenges posed by a canal, making it a more viable and

strategically balanced solution.

Geopolitical Stakes

Why the Kra Canal Matters

If constructed, the Kra Canal would provide a strategic alternative to the Strait of Malacca, reducing shipping distances by approximately

1,200 nautical miles. This shortcut would save fuel costs, cut transit

times, and ease congestion in the Strait of Malacca, which currently

handles nearly 94,000 vessel passages annually. As global trade continues to expand,

particularly in energy and container shipping, the demand for efficient

and secure maritime routes is higher than ever. The canal would create

an additional passage, reducing bottlenecks and alleviating concerns

about over-reliance on a single trade route.

China, as the world’s largest

trading nation, would stand to benefit immensely by reducing its

reliance on the Malacca Strait for energy imports and trade. Currently, approximately

80% of China’s oil imports pass through the Malacca Strait, making it a

critical vulnerability in times of geopolitical tensions. Diversifying

maritime routes through the Kra Canal could enhance China’s energy

security, providing an alternative supply chain for crude oil and

liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports from the Middle East and Africa.

China-US Competition

For China, the Kra Canal would address its “Malacca dilemma“—the

vulnerability of its maritime trade routes to potential blockades by

rival naval forces, particularly the United States. A hypothetical

China-controlled canal would enhance Beijing’s control over its supply

chain and maritime security, while boosting its geopolitical influence

in the region. Notably, the canal would enable China to establish a

stronger presence in the Indian Ocean, allowing the PLA Navy greater operational flexibility and enhancing its ability to protect critical sea lanes.

The United States and its allies, particularly Singapore and India, oppose

the canal’s construction owing in large part to these geopolitical

considerations. A China-dominated Kra Canal could reduce Singapore’s

significance as a shipping hub, potentially diminishing its economic and

strategic value. Singapore, which benefits heavily from transshipment

fees and trade facilitation, would likely experience economic losses if

traffic were diverted to a new canal. India, which has growing concerns

over China’s increasing influence in the Indian Ocean, sees the Kra

Canal as another strategic asset that could strengthen China’s maritime

footprint near its sphere of influence....

....MUCH MORE

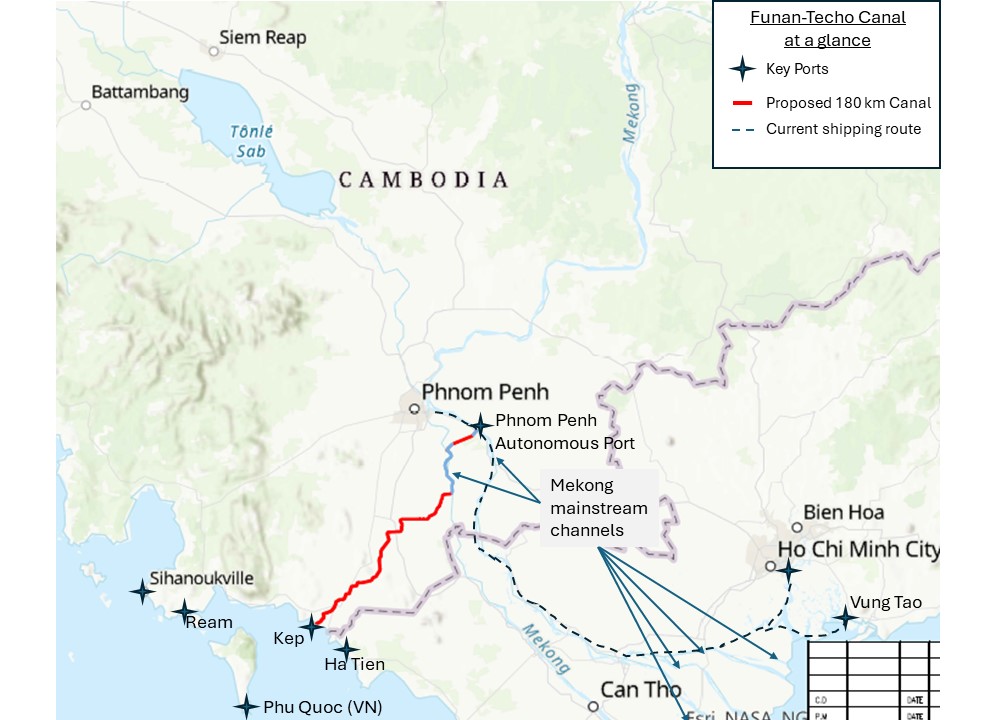

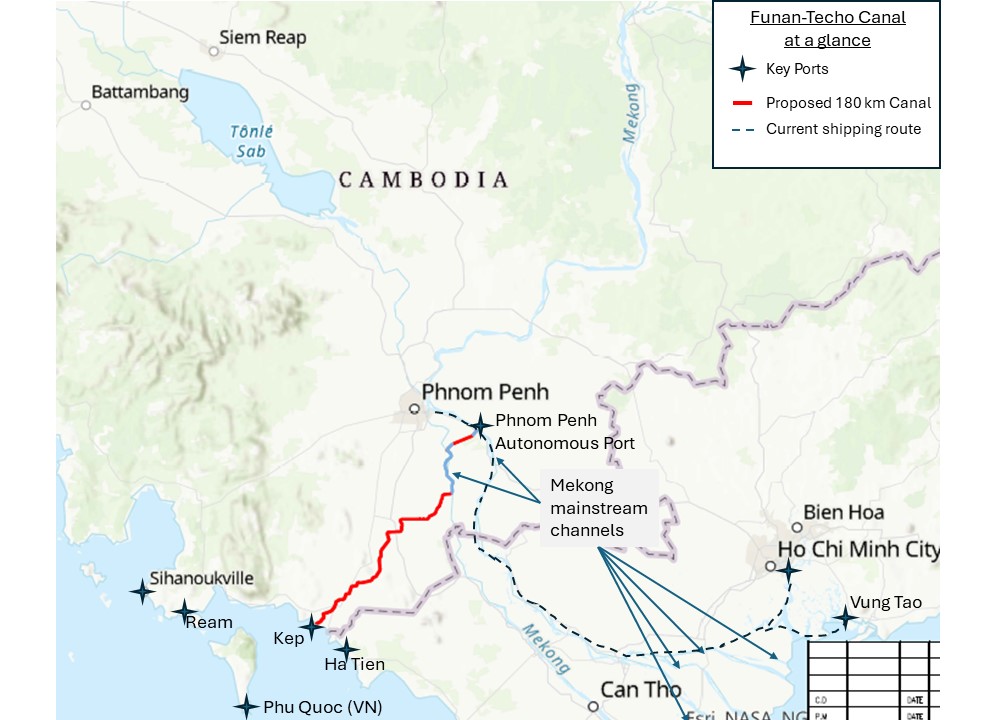

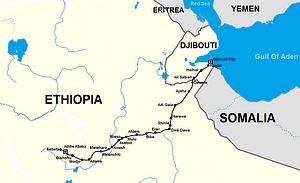

You can see how this project ties in with China's naval base across the Gulf of Thailand on Cambodia's west coast at Ream:

From April 22's "RAND: "The Gulf of Thailand May Be the Next U.S.-China Flashpoint":

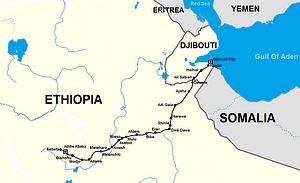

In fact the Kra canal project would allow China's navy a much more direct route to their only other overseas base on the route into the Suez Canal.

February 2024 - "Red Sea Rivalries"

The most amazing thing that has been pointed out over the last couple

months is that China's base on Djibouti's Gulf of Aden coast, at the

approaches to the Bab al-Mandab chokepoint into the Red Sea, gives them

the perfect location to monitor Houthi action and American reaction:

—China Officially Sets Up Its First Overseas Base in Djibouti, The Diplomat

From Phenomenal World, February 15....