...The Dutch 'Wind-trade', which also popped and dropped during those memorable months of 1719 - 1720?

From Professor (Erasmus U., Rotterdam) David Smant's personal website:

DUTCH MIRROR OF FOLLY, Windhandel 1720

.....Published by various connoisseurs, in order

to taunt this despicable and deceiving trade, by which in this year,

several families and persons of high and low standing were ruined, and

depraved of their resources, and the real trade halted, in France,

England and the Netherlands.

As long as the greedy person, Has money and goods,

The swindler will get his way,

Because the greedy and feeble-minded will always supply him.

[The Great Picture of Folly, 1720]

The scene is set. This is the text on the

cover page of one of the main sources of information about what has

become known as the Dutch 'windhandel' (wind trade) of 1720. Hardly a

strong recommendation for objective and serious analysis of this episode

in Dutch share trading. The Great Picture of Folly consists of a

collection of cartoons, comedies and satires, poems and a few texts

depicting the short-lived boom in Dutch joint-stock companies.

Approximately 40+ joint-stock companies were proposed and founded in the

period June-October 1720. Most of these companies were designed to

follow the recent English example for joint-stock assurance companies

(aiming to replace the existing private, individual insurance

underwriting) although their plans also included various combinations of

commercial (e.g. shipping and trade) and financial (loans and

lotteries) activities. Besides the fact that the proposed joint-stock

companies required an official charter, their planning and organization

included a close cooperation with the Dutch city governments (today that

would be called public-private partnership).

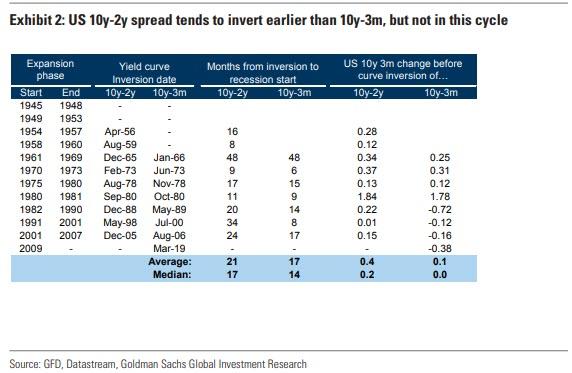

The following table presents a survey of

most of the Dutch companies and the available information on key

features with respect to date, nominal capital and nominal share value.

Eight of the proposed companies were stopped at an early stage, mostly

because official consent was not obtained. All the projects followed

each other within a very short time frame from June to October 1720. The

most important feature was perhaps that the proposals with respect to

share capital included a large maximum share capital that in most cases

was not at all intended to be called on short notice. Most initial calls

of share capital were between 1 and 15 percent. The maximum share

capital seems to have functioned as an upper limit on shareholder

liability (particularly in the case of the insurance companies) and as a

shareholder commitment to supply future funds (something we today would

compare to loan commitments or credit lines offered by banks). The

effective nominal value of shares should be adjusted accordingly; only

the percentage called or paid-in capital amount is relevant. As is clear

from the final rows in the table, from the enormous amount of 363 mln

guilder capital (more than 800 mln guilder incl. the stopped projects)

only 41 mln gld of capital was actually called to start company

operations. Still a large amount of money, but of course of a different

order than the exaggerated 363 or 800 million that others like to

emphasize when commenting on this episode.

[Note: The table is

constructed using information from various sources. Information

published is not always reliable and frequently confusing because the

situation was constantly changing with many companies adjusting their

subscription conditions during 1720 and later. Pct. capital called

refers to the total, not merely the first installment that is reported

in some sources. The Societeit Berbice is treated separately because

although founded in the same period, its origin was not related to the

other assurance and commerce projects. A few other proposals may have

circulated at the time, informally with little information or simply

unknown to us today. A unique printed price list for the daily prices on

the Amsterdam exchange, dated 25Sep1720, lists 26 domestic compagnies,

and includes companies in Schoonhoven and Staveren but these two

companies' shares had no prices. Embden is located in Germany but right

on the border with the Netherlands.]

Joint-stock (marine) insurance companies

As mentioned before, half or more of the

proposed Dutch joint-stock companies mentioned assurance as one of their

important activities. At the time, the joint-stock insurance activities

could perhaps be viewed as an attractive major new business

opportunity. The share prices of some of the important assurance

compagnies (Stad Rotterdam, Middelburg Assurantie, and also Delft,

Gouda) do suggest they contain a premium over the other compagnies (see

the graph of share prices below). The proposed other, frequently

somewhat unfocused, commercial activities must probably be viewed as

essentially serious attempts of public-private partnerships to

accumulate funds of capital that were needed or desired to stimulate the

various local economies; the Dutch economy was (probably) experiencing a

somewhat difficult conjuncture period that had started approx. a year

earlier (1719).

The importance and subsequent experience of

the joint-stock insurance companies is perhaps aptly described by the

following text [adapted from Kingston (2007, JEH): Marine insurance in

Britain and America, 1720-1844: A comparative institutional analysis]

At the start of the 18th century, marine insurance in

Britain was carried out entirely by private individuals. Many

underwriters were merchants who wrote insurance on the side, but any

wealthy individual could underwrite a policy. A merchant (or a broker

acting on his behalf) wishing to purchase insurance drew up a policy and

presented it to private underwriters for their signature. Risks were

usually shared among several underwriters. The parties negotiated a

premium, and the underwriter wrote on the policy the amount he was

willing to insure.

In 1717 several groups of merchants and speculators

began petitioning to obtain charters for joint-stock marine insurance

corporations. The promoters argued that the proposed corporations would

provide cheaper and more secure insurance than the existing system of

private underwriters. Their underwriting would be backed by a large

capital fund, and in the event of a claim, it would be easier for a

merchant to recover losses from a corporation than from many individual

underwriters separately. Corporations also expanded the pool of

available capital by enabling those without specialist knowledge of

marine risks, or with relatively modest amounts of capital, to act as

insurers by entrusting their underwriting decisions to experts. The

proposed charters were opposed by merchants and private underwriters in

London and Bristol, who claimed that the existing system was adequate,

and that a monopoly would harm trade. Both sides in the debate, however,

shared the expectation that if charters were granted, the proposed

corporations would drive private underwriters out of the market. The

argument was settled when the two main groups of promoters offered the

King £600,000 (to pay off the debt on the Civil List) in exchange for

charters.

Two joint stock corporations (the Royal Exchange Assurance and

the London Assurance) were subsequently incorporated as part of what

later became known as the “Bubble Act” of 1720. The Bubble Act made it

illegal for joint-stock companies to operate without a corporate

charter.

In all industries except marine insurance, however, other kinds

of unincorporated companies, including partnerships and trusts, were

still allowed, and businessmen were later able to use these devices to

create (highly imperfect) substitutes for the joint-stock business

corporation (Harris, 2000)....

....

MUCH MORE

Professor Smant's homepage.

See also

the Rijksmuseum