Your parents’ — more likely your grandparents’ — Great Depression opened with the then-biggest-ever stock market crash, continued with the largest-ever sustained decline in GDP, and ended with a near-decade of subnormal production and employment. Yet 11 years after the 1929 crash, national income per worker was 10 percent above its 1929 level. The next year, 12 years after, it was 28 percent above its 1929 level. The economy had fully recovered. And then came the boom of World War II, followed by the “thirty glorious years” of post-World War II prosperity.

The Great Depression was a nightmare. But the economy then woke up — and it was not haunted thereafter.

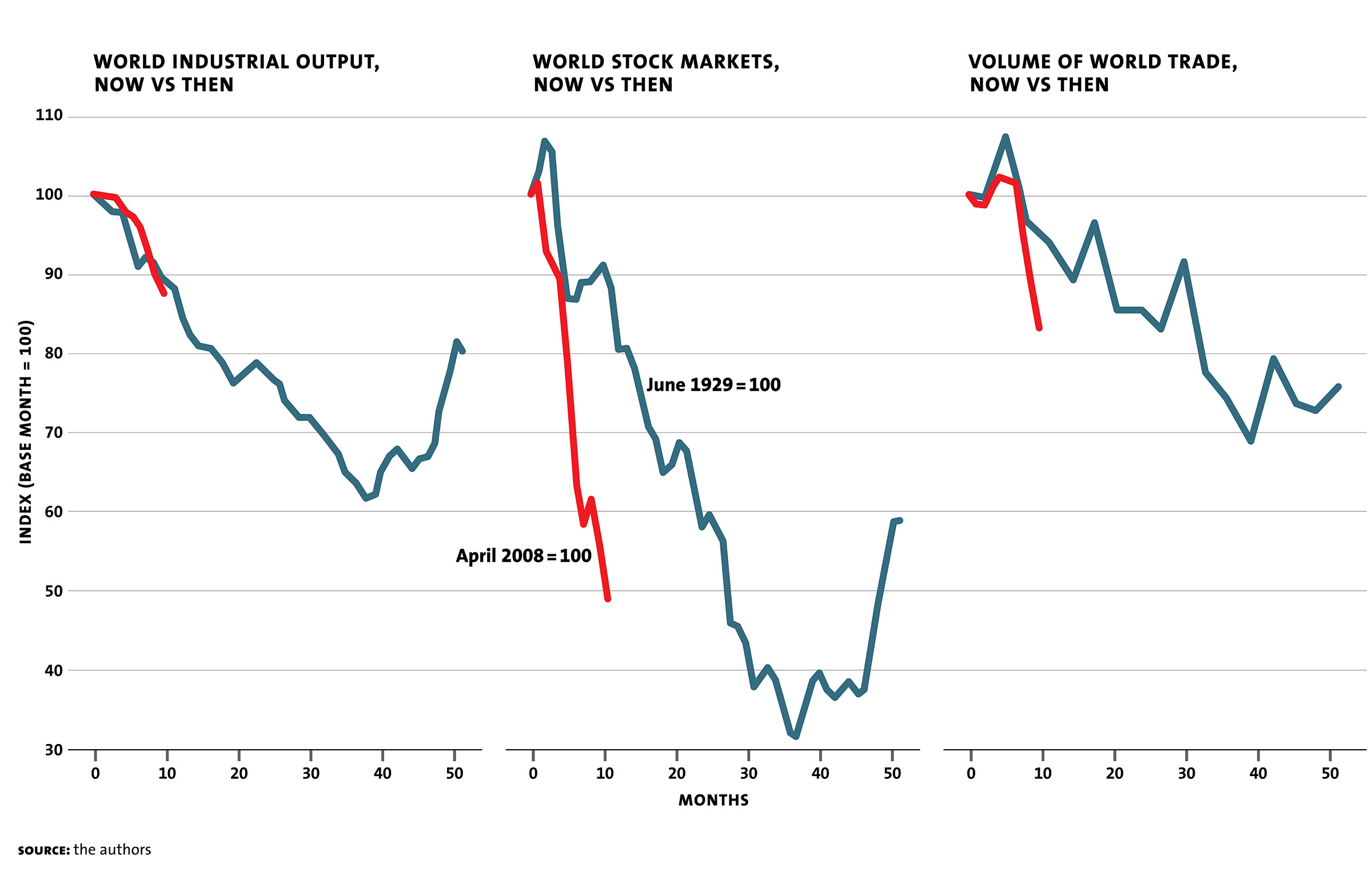

Our “Great Recession” opened in 2007 with what appeared to be a containable financial crisis. The economy subsequently danced on a knife-edge of instability for a year. Then came the crash — in stock market values, employment and GDP. The experience of the Great Depression, however, gave policymakers the knowledge and running room to keep our depression-in-the-making an order of magnitude less severe than the Great Depression.

That’s all true. But it’s not the whole story. The Great Recession has cast a very large shadow on America’s future prosperity. We are still haunted by it. Indeed, this is the year, the eleventh after the start of the crisis, when national income per worker relative to its pre-crisis benchmark begins to lose the race to recovery relative to the Great Depression.

But, you may ask, didn’t World War II come along to “rescue” the U.S. economy after the Great Depression? Isn’t the fact that output per worker in 1941 vastly surpassed the 1929 benchmark explained by circumstance — by the reality that the United States was urgently mobilizing for a war of necessity against Nazi Germany and imperial Japan?

Not so fast. Defense spending was only 1.7 percent of national income in 1940, and grew to only 5.5 percent of national income in 1941. The near-total mobilization that carried production above its long-term sustainable potential did not begin until after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941.

Seen from this perspective, we seem to have fumbled the recovery from the recession. To be sure, anticyclical policies — fiscal stimulus under two presidents and an unprecedented effort to drive interest rates below zero by the Fed — have been broadly successful in the years since 2007. The Great Depression was far deeper than the Great Recession, losing an extra year’s output before recovery. But now we are haunted by our Great Recession in a sense that our predecessors were not haunted by the Great Depression. Looking forward, it appears that we will be haunted for who knows how long. No unbiased observer projects anything other than slow growth, much slower than the years during and after World War II. Nobody is forecasting that the haunting will cease — that the shadow left from the Great Recession will lift.

The policymakers of the 1920s had little idea that a collapse in production of anything like the magnitude of the Great Depression was even possible. Earlier downturns, though often quite deep, were brief. The policymakers of the 2000s, by contrast, knew very well that catastrophe was possible.

Then there’s the issue of what the policymakers thought they could do to counter the business cycle. Those in charge in the 1920s knew about — and ought to have depended on — what’s referred to as the “rule” of Walter Bagehot. The editor of The Economist in the 1860s and 70s, Bagehot set out the principle in the book Lombard Street: A Study of the Money Market: in a crisis, lend freely, at a penalty rate, on collateral that is good in normal times, and strain every nerve to keep the collapse of systemically important financial institutions from producing contagion and panic.

Bagehot’s rule, in fact, isn’t a bad place to start in a financial crisis. But for economists of the era, there was also the “liquidationist” intellectual tradition of Friedrich von Hayek, Herbert Hoover, Andrew Mellon and Karl Marx to be reckoned with — what amounts to economic Darwinism. The “cold douche” of large-scale bankruptcy, as Joseph Schumpeter called it, would ultimately be good for — and was perhaps essential to — the ongoing health of a market economy. Thankfully, after the Great Depression, survival of the fittest was no longer economic gospel.

Oddly, though, the Federal Reserve and Treasury of 2008 clung to an overly literal and selective reading of Bagehot’s rule. Both stood by as Lehman Brothers, a systemically important financial institution if there ever was one, headed for bankruptcy with no option for reorganization. And the event did, indeed, lead to large-scale contagion and panic.

The Fed and the Treasury have since claimed they had no choice in the fall of 2008. Lehman Brothers, you see, was not just illiquid but insolvent. It had no good collateral. The federal government lacked the legal authority to lend to an insolvent institution, and thus could not apply the Bagehot rule — unless you remembered that the collateral only had to be “good in normal times.”

If this is, in fact, the real explanation for their inaction, it seems to me an astonishing admission of incompetence in financial crisis management and central banking. For authorities to allow a systemically important financial player to linger, mortally wounded, while it went from barely to deeply insolvent is malpractice of a very high order. If a too-big-to-fail institution cannot be backstopped in a crisis, it must be shut down the moment it begins to unravel. It is, after all, too big to be allowed to fail in an uncontrolled manner.

However, after the 2008 crisis grew to economy-shaking proportions and a genuine depression seemed imminent, policymakers did redeem themselves. The deciders of the early 1930s had stood by wringing their hands and doing nothing productive as the economy collapsed. By contrast, their counterparts of the late 2000s swung into action with the right policies at the right moment — albeit policies of insufficient scale and force....

...MUCH MORE