From Eurozine, March 2, 2018:

(at least, the part that’s already happened)

Read in: EN / UK / FR / ET / IT / NO / PT / PL / SL

The story we have been telling ourselves about our origins is wrong, and perpetuates the idea of inevitable social inequality. David Graeber and David Wengrow ask why the myth of ‘agricultural revolution’ remains so persistent, and argue that there is a whole lot more we can learn from our ancestors.

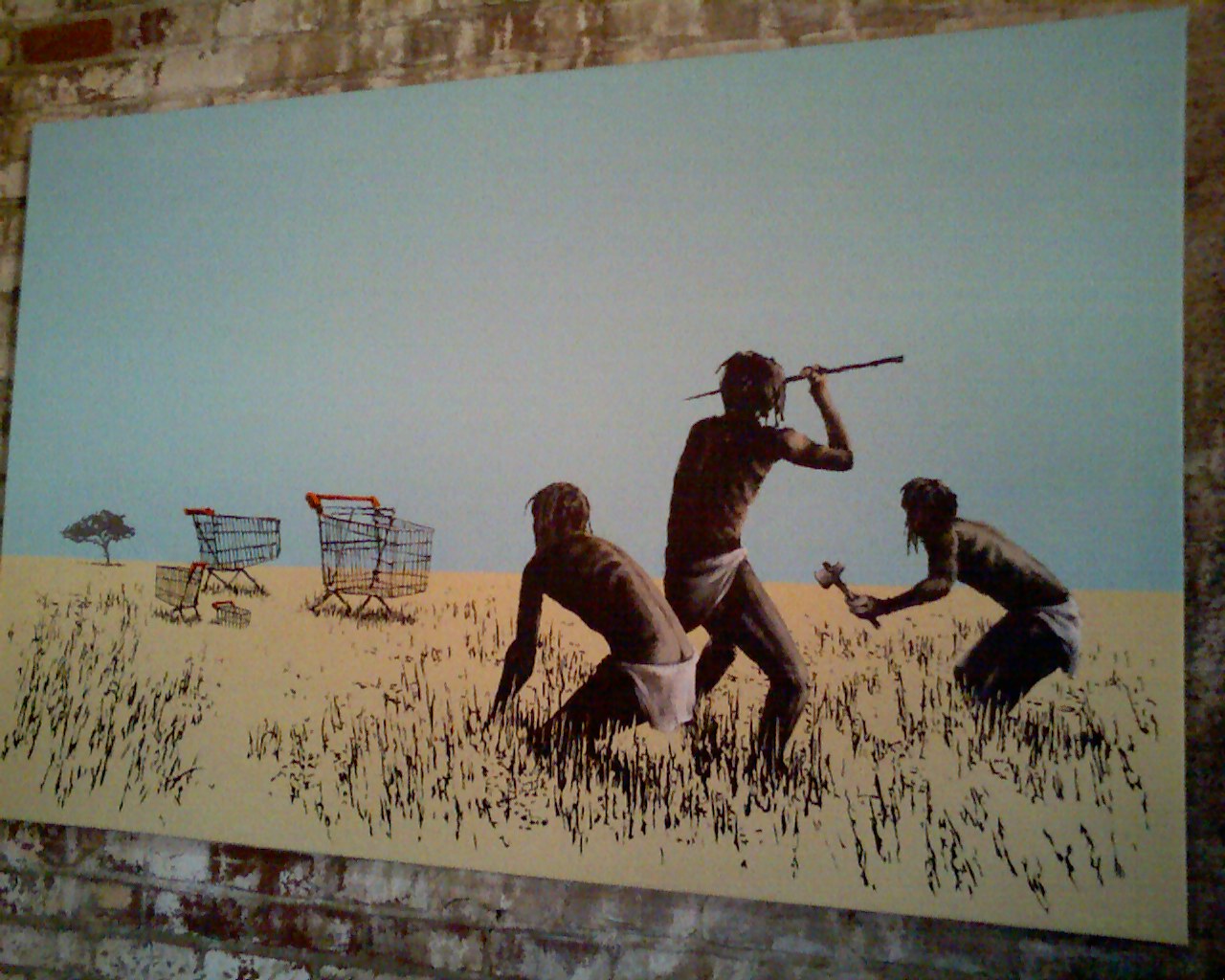

Art work by Banksy (title unknown). Source: Flickr

1. In the beginning was the wordFor centuries, we have been telling ourselves a simple story about the origins of social inequality. For most of their history, humans lived in tiny egalitarian bands of hunter-gatherers. Then came farming, which brought with it private property, and then the rise of cities which meant the emergence of civilization properly speaking. Civilization meant many bad things (wars, taxes, bureaucracy, patriarchy, slavery…) but also made possible written literature, science, philosophy, and most other great human achievements.

Almost everyone knows this story in its broadest outlines. Since at least the days of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, it has framed what we think the overall shape and direction of human history to be. This is important because the narrative also defines our sense of political possibility. Most see civilization, hence inequality, as a tragic necessity. Some dream of returning to a past utopia, of finding an industrial equivalent to ‘primitive communism’, or even, in extreme cases, of destroying everything, and going back to being foragers again. But no one challenges the basic structure of the story.

There is a fundamental problem with this narrative.

It isn’t true.

Overwhelming evidence from archaeology, anthropology, and kindred disciplines is beginning to give us a fairly clear idea of what the last 40,000 years of human history really looked like, and in almost no way does it resemble the conventional narrative. Our species did not, in fact, spend most of its history in tiny bands; agriculture did not mark an irreversible threshold in social evolution; the first cities were often robustly egalitarian. Still, even as researchers have gradually come to a consensus on such questions, they remain strangely reluctant to announce their findings to the public – or even scholars in other disciplines – let alone reflect on the larger political implications. As a result, those writers who are reflecting on the ‘big questions’ of human history – Jared Diamond, Francis Fukuyama, Ian Morris, and others – still take Rousseau’s question (‘what is the origin of social inequality?’) as their starting point, and assume the larger story will begin with some kind of fall from primordial innocence.

Simply framing the question this way means making a series of assumptions, that 1. there is a thing called ‘inequality,’ 2. that it is a problem, and 3. that there was a time it did not exist. Since the financial crash of 2008, of course, and the upheavals that followed, the ‘problem of social inequality’ has been at the centre of political debate. There seems to be a consensus, among the intellectual and political classes, that levels of social inequality have spiralled out of control, and that most of the world’s problems result from this, in one way or another. Pointing this out is seen as a challenge to global power structures, but compare this to the way similar issues might have been discussed a generation earlier. Unlike terms such as ‘capital’ or ‘class power’, the word ‘equality’ is practically designed to lead to half-measures and compromise. One can imagine overthrowing capitalism or breaking the power of the state, but it’s very difficult to imagine eliminating ‘inequality’. In fact, it’s not obvious what doing so would even mean, since people are not all the same and nobody would particularly want them to be.

‘Inequality’ is a way of framing social problems appropriate to technocratic reformers, the kind of people who assume from the outset that any real vision of social transformation has long since been taken off the political table. It allows one to tinker with the numbers, argue about Gini coefficients and thresholds of dysfunction, readjust tax regimes or social welfare mechanisms, even shock the public with figures showing just how bad things have become (‘can you imagine? 0.1% of the world’s population controls over 50% of the wealth!’), all without addressing any of the factors that people actually object to about such ‘unequal’ social arrangements: for instance, that some manage to turn their wealth into power over others; or that other people end up being told their needs are not important, and their lives have no intrinsic worth. The latter, we are supposed to believe, is just the inevitable effect of inequality, and inequality, the inevitable result of living in any large, complex, urban, technologically sophisticated society. That is the real political message conveyed by endless invocations of an imaginary age of innocence, before the invention of inequality: that if we want to get rid of such problems entirely, we’d have to somehow get rid of 99.9% of the Earth’s population and go back to being tiny bands of foragers again. Otherwise, the best we can hope for is to adjust the size of the boot that will be stomping on our faces, forever, or perhaps to wrangle a bit more wiggle room in which some of us can at least temporarily duck out of its way.

Mainstream social science now seems mobilized to reinforce this sense of hopelessness. Almost on a monthly basis we are confronted with publications trying to project the current obsession with property distribution back into the Stone Age, setting us on a false quest for ‘egalitarian societies’ defined in such a way that they could not possibly exist outside some tiny band of foragers (and possibly, not even then). What we’re going to do in this essay, then, is two things. First, we will spend a bit of time picking through what passes for informed opinion on such matters, to reveal how the game is played, how even the most apparently sophisticated contemporary scholars end up reproducing conventional wisdom as it stood in France or Scotland in, say, 1760. Then we will attempt to lay down the initial foundations of an entirely different narrative. This is mostly ground-clearing work. The questions we are dealing with are so enormous, and the issues so important, that it will take years of research and debate to even begin understanding the full implications. But on one thing we insist. Abandoning the story of a fall from primordial innocence does not mean abandoning dreams of human emancipation – that is, of a society where no one can turn their rights in property into a means of enslaving others, and where no one can be told their lives and needs don’t matter. To the contrary. Human history becomes a far more interesting place, containing many more hopeful moments than we’ve been led to imagine, once we learn to throw off our conceptual shackles and perceive what’s really there.

2. Contemporary authors on the origins of social inequality; or, the eternal return of Jean-Jacques RousseauLet us begin by outlining received wisdom on the overall course of human history. It goes something a little like this:

As the curtain goes up on human history – say, roughly two hundred thousand years ago, with the appearance of anatomically modern Homo sapiens – we find our species living in small and mobile bands ranging from twenty to forty individuals. They seek out optimal hunting and foraging territories, following herds, gathering nuts and berries. If resources become scarce, or social tensions arise, they respond by moving on, and going someplace else. Life for these early humans – we can think of it as humanity’s childhood – is full of dangers, but also possibilities. Material possessions are few, but the world is an unspoiled and inviting place. Most work only a few hours a day, and the small size of social groups allows them to maintain a kind of easy-going camaraderie, without formal structures of domination. Rousseau, writing in the 18th century, referred to this as ‘the State of Nature,’ but nowadays it is presumed to have encompassed most of our species’ actual history. It is also assumed to be the only era in which humans managed to live in genuine societies of equals, without classes, castes, hereditary leaders, or centralised government.

Alas this happy state of affairs eventually had to end. Our conventional version of world history places this moment around 10,000 years ago, at the close of the last Ice Age.

At this point, we find our imaginary human actors scattered across the world’s continents, beginning to farm their own crops and raise their own herds. Whatever the local reasons (they are debated), the effects are momentous, and basically the same everywhere. Territorial attachments and private ownership of property become important in ways previously unknown, and with them, sporadic feuds and war. Farming grants a surplus of food, which allows some to accumulate wealth and influence beyond their immediate kin-group. Others use their freedom from the food-quest to develop new skills, like the invention of more sophisticated weapons, tools, vehicles, and fortifications, or the pursuit of politics and organised religion. In consequence, these ‘Neolithic farmers’ quickly get the measure of their hunter-gatherer neighbours, and set about eliminating or absorbing them into a new and superior – albeit less equal – way of life.

To make matters more difficult still, or so the story goes, farming ensures a global rise in population levels. As people move into ever-larger concentrations, our unwitting ancestors take another irreversible step to inequality, and around 6,000 years ago, cities appear – and our fate is sealed. With cities comes the need for centralised government. New classes of bureaucrats, priests, and warrior-politicians install themselves in permanent office to keep order and ensure the smooth flow of supplies and public services. Women, having once enjoyed prominent roles in human affairs, are sequestered, or imprisoned in harems. War captives are reduced to slaves. Full-blown inequality has arrived, and there is no getting rid of it. Still, the story-tellers always assure us, not everything about the rise of urban civilization is bad. Writing is invented, at first to keep state accounts, but this allows terrific advances to take place in science, technology, and the arts. At the price of innocence, we became our modern selves, and can now merely gaze with pity and jealousy at those few ‘traditional’ or ‘primitive’ societies that somehow missed the boat.

This is the story that, as we say, forms the foundation of all contemporary debate on inequality. If say, an expert in international relations, or a clinical psychologist, wishes to reflect on such matters, they are likely to simply take it for granted that, for most of human history, we lived in tiny egalitarian bands, or that the rise of cities also meant the rise of the state. The same is true of most recent books that try to look at the broad sweep of prehistory, in order to draw political conclusions relevant to contemporary life. Consider Francis Fukuyama’s The Origins of Political Order: From Prehuman Times to the French Revolution:

In its early stages, human political organization is similar to the band-level society observed in higher primates like chimpanzees. This may be regarded as a default form of social organization. … Rousseau pointed out that the origin of political inequality lay in the development of agriculture, and in this he was largely correct. Since band-level societies are preagricultural, there is no private property in any modern sense. Like chimp bands, hunter-gatherers inhabit a territorial range that they guard and occasionally fight over. But they have a lesser incentive than agriculturalists to mark out a piece of land and say ‘this is mine’. If their territory is invaded by another group, or if it is infiltrated by dangerous predators, band-level societies may have the option of simply moving somewhere else due to low population densities. Band-level societies are highly egalitarian … Leadership is vested in individuals based on qualities like strength, intelligence, and trustworthiness, but it tends to migrate from one individual to another.

Jared Diamond, in World Before Yesterday: What Can We Learn from Traditional Societies?, suggests such bands (in which he believes humans still lived ‘as recently as 11,000 years ago’) comprised ‘just a few dozen individuals’, most biologically related. They led a fairly meagre existence, ‘hunting and gathering whatever wild animal and plant species happen to live in an acre of forest’. (Why just an acre, he never explains). And their social lives, according to Diamond, were enviably simple. Decisions were reached through ‘face-to-face discussion’; there were ‘few personal possessions’, and ‘no formal political leadership or strong economic specialization’. Diamond concludes that, sadly, it is only within such primordial groupings that humans have ever achieved a significant degree of social equality.

For Diamond and Fukuyama, as for Rousseau some centuries earlier, what put an end to that equality – everywhere and forever – was the invention of agriculture and the higher population levels it sustained. Agriculture brought about a transition from ‘bands’ to ‘tribes’. Accumulation of food surplus fed population growth, leading some ‘tribes’ to develop into ranked societies known as ‘chiefdoms’. Fukuyama paints an almost biblical picture, a departure from Eden: ‘As little bands of human beings migrated and adapted to different environments, they began their exit out of the state of nature by developing new social institutions’. They fought wars over resources. Gangly and pubescent, these societies were headed for trouble.

It was time to grow up, time to appoint some proper leadership. Before long, chiefs had declared themselves kings, even emperors. There was no point in resisting. All this was inevitable once humans adopted large, complex forms of organization. Even when the leaders began acting badly – creaming off agricultural surplus to promote their flunkies and relatives, making status permanent and hereditary, collecting trophy skulls and harems of slave-girls, or tearing out rival’s hearts with obsidian knives – there could be no going back. ‘Large populations’, Diamond opines, ‘can’t function without leaders who make the decisions, executives who carry out the decisions, and bureaucrats who administer the decisions and laws. Alas for all of you readers who are anarchists and dream of living without any state government, those are the reasons why your dream is unrealistic: you’ll have to find some tiny band or tribe willing to accept you, where no one is a stranger, and where kings, presidents, and bureaucrats are unnecessary’.

A dismal conclusion, not just for anarchists, but for anybody who ever wondered if there might be some viable alternative to the status quo. But the remarkable thing is that, despite the smug tone, such pronouncements are not actually based on any kind of scientific evidence. There is no reason to believe that small-scale groups are especially likely to be egalitarian, or that large ones must necessarily have kings, presidents, or bureaucracies. These are just prejudices stated as facts.

In the case of Fukuyama and Diamond one can, at least, note they were never trained in the relevant disciplines (the first is a political scientist, the other has a PhD on the physiology of the gall bladder). Still, even when anthropologists and archaeologists try their hand at ‘big picture’ narratives, they have an odd tendency to end up with some similarly minor variation on Rousseau. In The Creation of Inequality: How our Prehistoric Ancestors Set the Stage for Monarchy, Slavery, and Empire, Kent Flannery and Joyce Marcus, two eminently qualified scholars, lay out some five hundred pages of ethnographic and archaeological case studies to try and solve the puzzle. They admit our Ice Age forbears were not entirely unfamiliar with institutions of hierarchy and servitude, but insist they experienced these mainly in their dealings with the supernatural (ancestral spirits, and the like). The invention of farming, they propose, led to the emergence of demographically extended ‘clans’ or ‘descent groups’, and as it did so, access to spirits and the dead became a route to earthly power (how, exactly, is not made clear). According to Flannery and Marcus, the next major step on the road to inequality came when certain clansmen of unusual talent or renown – expert healers, warriors, and other over-achievers – were granted the right to transmit status to their descendants, regardless of the latter’s talents or abilities. That pretty much sowed the seeds, and meant from then on, it was just a matter of time before the arrival of cities, monarchy, slavery and empire.

The curious thing about Flannery and Marcus’ book is that only with the birth of states and empires do they really bring in any archaeological evidence. All the really key moments in their account of the ‘creation of inequality’ rely instead on relatively recent descriptions of small-scale foragers, herders, and cultivators like the Hadza of the East African Rift, or Nambikwara of the Amazonian rainforest. Accounts of such ‘traditional societies’ are treated as if they were windows onto the Palaeolithic or Neolithic past. The problem is that they are nothing of the kind. The Hadza or Nambikwara are not living fossils. They have been in contact with agrarian states and empires, raiders and traders, for millennia, and their social institutions were decisively shaped through attempts to engage with, or avoid them. Only archaeology can tell us what, if anything, they have in common with prehistoric societies. So, while Flannery and Marcus provide all sorts of interesting insights into how inequalities might emerge in human societies, they give us little reason to believe that this was how they actually did.

Finally, let us consider Ian Morris’s Foragers, Farmers, and Fossil Fuels: How Human Values Evolve. Morris is pursuing a slightly different intellectual project: to bring the findings of archaeology, ancient history, and anthropology into dialogue with the work of economists, such as Thomas Piketty on the causes of inequality in the modern world, or Sir Tony Atkinson’s more policy-oriented Inequality: What can be Done? The ‘deep time’ of human history, Morris informs us, has something important to tell us about such questions – but only if we first establish a uniform measure of inequality applicable across its entire span. This he achieves by translating the ‘values’ of Ice Age hunter-gatherers and Neolithic farmers into terms familiar to modern-day economists, and then using those to establish Gini coefficients, or formal inequality rates. Instead of the spiritual inequities that Flannery and Marcus highlight, Morris gives us an unapologetically materialist view, dividing human history into the three big ‘Fs’ of his title, depending on how they channel heat. All societies, he suggests, have an ‘optimal’ level of social inequality – a built-in ‘spirit-level’ to use Pickett and Wilkinson’s term – that is appropriate to their prevailing mode of energy extraction.

In a 2015 piece for the New York Times Morris actually gives us numbers, quantified primordial incomes in USD and fixed to 1990 currency values.1 He too assumes that hunter-gatherers of the last Ice Age lived mostly in tiny mobile bands. As a result, they consumed very little, the equivalent, he suggests, of about $1.10/day. Consequently, they also enjoyed a Gini coefficient of around 0.25 – that is, about as low as such rates can go – since there was little surplus or capital for any would-be elite to grab. Agrarian societies – and for Morris this includes everything from the 9,000-year-old Neolithic village of Çatalhöyük to Kublai Khan’s China or the France of Louis XIV – were more populous and better off, with an average consumption of $1.50-$2.20/day per person, and a propensity to accumulate surpluses of wealth. But most people also worked harder, and under markedly inferior conditions, so farming societies tended towards much higher levels of inequality.

Fossil-fuelled societies should really have changed all that by liberating us from the drudgery of manual work, and bringing us back towards more reasonable Gini coefficients, closer to those of our hunter-forager ancestors – and for a while it seemed like this was beginning to happen, but for some odd reason, which Morris doesn’t completely understand, matters have gone into reverse again and wealth is once again sucked up into the hands of a tiny global elite:

If the twists and turns of economic history over the last 15,000 years and popular will are any guide, the ‘right’ level of post-tax income inequality seems to lie between about 0.25 and 0.35, and that of wealth inequality between about 0.70 and 0.80. Many countries are now at or above the upper bounds of these ranges, which suggests that Mr. Piketty is indeed right to foresee trouble.

Some major technocratic tinkering is clearly in order!

Let us leave Morris’ prescriptions aside but just focus on one figure: the Palaeolithic income of $1.10 a day. Where exactly does it come from? Presumably the calculations have something to do with the calorific value of daily food intake. But if we’re comparing this to daily incomes today, wouldn’t we also have to factor in all the other things Palaeolithic foragers got for free, but which we ourselves would expect to pay for: free security, free dispute resolution, free primary education, free care of the elderly, free medicine, not to mention entertainment costs, music, storytelling, and religious services? Even when it comes to food, we must consider quality: after all, we’re talking about 100% organic free-range produce here, washed down with purest natural spring water. Much contemporary income goes to mortgages and rents. But consider the camping fees for prime Palaeolithic locations along the Dordogne or the Vézère, not to mention the high-end evening classes in naturalistic rock painting and ivory carving – and all those fur coats. Surely all this must cost wildly in excess of $1.10/day, even in 1990 dollars. It’s not for nothing that Marshall Sahlins referred to foragers as ‘the original affluent society.’ Such a life today would not come cheap.

This is all admittedly a bit silly, but that’s kind of our point: if one reduces world history to Gini coefficients, silly things will, necessarily, follow. Also depressing ones. Morris at least feels something is askew with the recent galloping increases of global inequality. By contrast, historian Walter Scheidel has taken Piketty-style readings of human history to their ultimate miserable conclusion in his 2017 book The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century, concluding there’s really nothing we can do about inequality. Civilization invariably puts in charge a small elite who grab more and more of the pie. The only thing that has ever been successful in dislodging them is catastrophe: war, plague, mass conscription, wholesale suffering and death. Half measures never work. So, if you don’t want to go back to living in a cave, or die in a nuclear holocaust (which presumably also ends up with the survivors living in caves), you’re going to just have to accept the existence of Warren Buffett and Bill Gates.

The liberal alternative? Flannery and Marcus, who openly identify with the tradition of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, end their survey with the following helpful suggestion:

3. But did we really run headlong for our chains?We once broached this subject with Scotty MacNeish, an archaeologist who had spent 40 years studying social evolution. How, we wondered, could society be made more egalitarian? After briefly consulting his old friend Jack Daniels, MacNeish replied, ‘Put hunters and gatherers in charge.’

The really odd thing about these endless evocations of Rousseau’s innocent State of Nature, and the fall from grace, is that Rousseau himself never claimed the State of Nature really happened. It was all a thought-experiment. In his Discourse on the Origin and the Foundation of Inequality Among Mankind (1754), where most of the story we’ve been telling (and retelling) originates, he wrote:

… the researches, in which we may engage on this occasion, are not to be taken for historical truths, but merely as hypothetical and conditional reasonings, fitter to illustrate the nature of things, than to show their true origin.

Rousseau’s ‘State of Nature’ was never intended as a stage of development. It was not supposed to be an equivalent to the phase of ‘Savagery’, which opens the evolutionary schemes of Scottish philosophers such as Adam Smith, Ferguson, Millar, or later, Lewis Henry Morgan. These others were interested in defining levels of social and moral development, corresponding to historical changes in modes of production: foraging, pastoralism, farming, industry. What Rousseau presented is, by contrast, more of a parable. As emphasised by Judith Shklar, the renowned Harvard political theorist, Rousseau was really trying to explore what he considered the fundamental paradox of human politics: that our innate drive for freedom somehow leads us, time and again, on a ‘spontaneous march to inequality’. In Rousseau’s own words: ‘All ran headlong for their chains in the belief that they were securing their liberty; for although they had enough reason to see the advantages of political institutions, they did not have enough experience to foresee the dangers’. The imaginary State of Nature is just a way of illustrating the point.....

****

....4. How the course of (past) history can now changeSo, what has archaeological and anthropological research really taught us, since the time of Rousseau?

Well, the first thing is that asking about the ‘origins of social inequality’ is probably the wrong place to start. True, before the beginning of what’s called the Upper Palaeolithic we really have no idea what most human social life was like. Much of our evidence comprises scattered fragments of worked stone, bone, and a few other durable materials. Different hominin species coexisted; it’s not clear if any ethnographic analogy might apply. Things only begin to come into any kind of focus in the Upper Palaeolithic itself, which begins around 45,000 years ago, and encompasses the peak of glaciation and global cooling (c. 20,000 years ago) known as the Last Glacial Maximum. This last great Ice Age was then followed by the onset of warmer conditions and gradual retreat of the ice sheets, leading to our current geological epoch, the Holocene. More clement conditions followed, creating the stage on which Homo sapiens – having already colonised much of the Old World – completed its march into the New, reaching the southern shores of the Americas by around 15,000 years ago....

....MUCH MORE

For what it's worth I have zero respect for Jared Diamond. After reading Guns, Germs and Steel I thought okay, interesting premise and exposition, I'll keep an eye on this one. From our April 2022 post "Kleptocracies":

I've mentioned:

One of the reasons we stopped paying attention to Jared Diamond after

Guns, Germs and Steel was his false take on what happened to the Easter

Islanders in his book, Collapse!*

More after the jump...

****

....Professor Diamond was so set on using Easter Island as an example of his ecocide thesis that he regurgitated it despite huge flaws in the theory at the time he was writing. And then:

It Wasn't 'Ecocide': What Happend On Easter Island

Jared Diamond has some explaining to do.*

From Chicago's Field Museum of Natural History, August 13, 2018 via PhysOrg:

Easter Island's society might not have collapsed

More on how he twists facts to fit his sales pitch, here on how great hunter-gatherers have it vs. peeps who practice agriculture:

"The Worst Mistake In The History Of The Human Race" – 1987 article by Jared Diamond

Diamond, at least since Guns, Germs and Steel, has struck me as lightweight, just coasting, trying to force observations into a prejudiced worldview. I know his impressive c.v. but it had gotten to the point where any time I read something of his I thought of Churchill's comment:

A fanatic is one who can't change his mind and won't change the subject.

It turns out that he was like that a quarter century ago.

More spleen venting below....

*****

.....This neo-Rousseau-ish babble makes me want to grab a mongongo nut and crack it on his head.

Painting the image of hunter-gatherer superiority he makes no mention of the agricultural peasants of the middle ages who worked between 180 and 260 days per year, the rest of the time being taken up with Sundays, feast days, holidays, fair days etc.

Denigrating the division of labor he makes no mention of the benefits that he has personally derived. I would estimate his Sasquatch-sized ecological footprint to be equivalent to 500-1000 Bushmen.

In many ways the best thing he could do, if he truly believed what he writes, is join the Voluntary Human Extinction Movement instead of jetting off to his next book-signing.

In the meantime we have 7 billion people to feed.

[link to his paper rotted, substitute http://www.zo.utexas.edu/courses/Thoc/Readings/Diamond_WorstMistake.pdf]

It appears I got sort of worked up.

"This neo-Rousseau-ish babble makes me want to grab a mongongo nut and crack it on his head."?Good grief, I don't even know the guy.